Morgan Freeman’s The Story of Us Raises Questions We All Should Be Thinking About

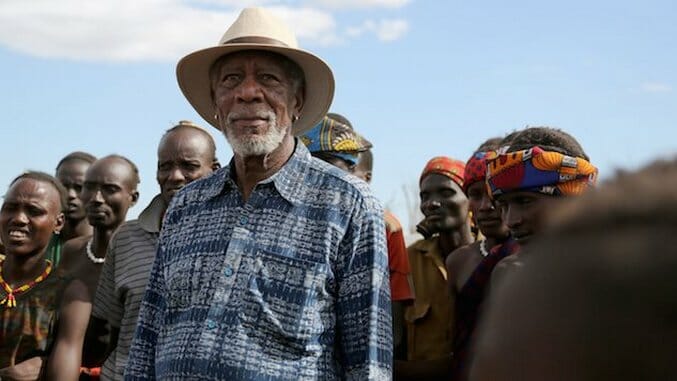

Photo: National Geographic/Maria Bohe TV Reviews The Story of Us

The broad-brush, what’s-it-all-about kind of questing or querying episodic documentary can take a few different forms based on narrative lens: Perhaps the focus is “nature,” and each episode investigates a different ecosystem, plant, animal. Perhaps it’s food, or travel, or society and politics, or some other cultural encyclopedia. Usually there is a narrator, either on or off-screen. Sometimes that person offers answers. Sometimes, questions.

Morgan Freeman’s The Story of Us, a six-episode follow-up to The Story of God, is question-oriented, and takes on modest little subjects like “peace,” or “freedom,” or “love” in a globe-crossing search for answers to some core questions: What forces hold human beings together? What is human society and where is it going? What do we truly have in common?

In a cultural moment when those questions are rather likely to provoke a depressing or combative response, it’s hard to imagine a better ambassador for the questions than Morgan Freeman. The guy is the dictionary definition of “sympathetic”; anyone who feels like they just cannot relate to this person should check an appropriate pressure point to make sure they have a pulse. He exudes a magical combination of charisma and humility, intelligence and down-to-earth-ness, curiosity and tranquility. He’s sincere and authoritative and you’ll likely follow him wherever he happens to be going.

The one-hour episodes are more broad than deep, taking the theme, for example, of love, and examining different expressions of it, from a well-off suburban British family whose Pakistani elders arranged their marriage to a soldier’s story of bonds forged in combat to an Ethiopian tribal group whose coming of age ceremony for young men involves the ritualized whipping of women. Most of the interview subjects are not famous (Bill Clinton is a conspicuous exception) or experts in anything but their own experiences—a man who grew up in a Romanian orphanage and his experience with adoption by American parents, a soldier who survived a six-hour firefight in Afghanistan, a London hairstylist.

The results are mixed; sometimes I found myself wishing he were interviewing someone else or spending more time on an interesting thread, expanding outward from one person’s story into a larger story of which it was representative. That doesn’t happen all that much. Freeman takes us from anecdote to anecdote, and the theme has no choice but to create a mosaic from the pieces. I think the choice to privilege “everyman” situations and people is wise in one way, but limits the narrative in another—since we’re tied to the storytelling capability of an interview subject rather than narrated to from an on-high voiceover, the insights and statements are only as good as the articulation power of the person speaking, and that isn’t always a ton. (Freeman’s chat with Albert Woodfox, a member of the famous “Angola Three” who spent four decades in solitary confinement, is a gleaming exception—he’s fascinating.) Sometimes people have fascinating stories but little talent for articulating them, and it can make you wish for a scripted element that tells those stories in more compelling language. Sometimes that gets in the way a bit. Other times it doesn’t.

Ultimately, the series is presented as a series of questions and a quest for a sort of chord of answers—varied tones combining into a single message. The message is an optimistic one: Freeman quietly insists that in the end freedom is available to anyone willing to fight for it, that peace is as much a human impulse as war, and that in fact all human beings are equally human and held together by sometimes not readily visible bonds of fellowship and love.

I’m with Freeman: All of these things strike me as 100% true, but (and it’s clear he gets this and that’s why this series exists), like Tinkerbell, they die when people stop believing in them. Right now, if you asked ten people in this country if they believe there is such a thing as freedom, I suspect at least half of them would say no. Freeman’s stories, the tiles of his mosaics, are selected very carefully, they are clearly in response to our current cultural moment, and they are designed to inspire questioning in a quiet, non-threatening way. Some people will probably take issue with “non-threatening.” And yes, this is a mild-mannered, human-scale docuseries. That is clearly a choice. Freeman doesn’t flinch from the concept of institutional oppression; he acknowledges it repeatedly, just not contemptuously or wrathfully. He doesn’t hide behind a polite veneer of mindful-tourist humility as he watches Ethiopian women being willingly and brutally whipped in a coming-of-age ceremony; he exclaims “But that’s abuse!” to the general bewilderment of the locals. The people participating in the ceremony don’t see it that way, and that’s as far as we go.

Sometimes it seems like it would feel good to go farther, go deeper, into some of the darker corners of the human psyche. What we get instead is a kind of Cook’s Tour of those places—aggression, enslavement, violence, oppression, power, control—and move on quickly to the next anecdote before people start to freak out or feel like there’s no hope. He’s a trustworthy guide; it’d be OK to trust the audience to hang in there for a little bit more of a deep dive on some of these stories. That it doesn’t necessarily do that should not suggest the series isn’t worth your time. It is. It’s artfully filmed, if very conventionally edited, and it brings up questions every human being should be thinking about, now and in general. If you have kids who are developmentally able to handle concepts like homelessness and incarceration and ritualized bare-knuckle fighting (um, and marriage), I highly recommend watching this show with them, actually. It’s not “for” a juvenile audience, but it also doesn’t exclude them, and it presents some pretty seriously necessary discussion points for people whose value systems are still forming.

Freeman is a transcendently non-divisive person on screen and this is a great project for him. I might have made some different choices if I were making the series, but that doesn’t mean mine would be better; just different. Some viewers might find it so non-confrontational in the face of difficult subjects that it’s frustrating; others might deeply appreciate the refusal to be that way, and either reaction would be valid. Almost any of the scenarios or people who get airtime in The Story of Us could be the subjects of a whole hour—or a whole season. But none of the time is wasted, and though Freeman’s message might seem pretty basic, I’d posit that “basic” needs a real good PR team right now: We’re all human, we all want love, we all fear death, we all want our lives to mean something, and we are all in this together, so you might as well embrace it, take responsibility for your mind, your choices, your actions, because as it turns out they all have significance.

That’s The Story of Us. And maybe we could all use a reminder.

The Story of Us premieres Wednesday, Oct. 11 at 9 p.m. on National Geographic.

Amy Glynn is a poet, essayist and fiction writer who really likes that you can multi-task by reviewing television and glasses of Cabernet simultaneously. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.