Release the Hound: Wishbone Creators on the Show’s History—and Its Uncertain Future

The beloved literary pup's creators were ready for a TV reboot ... until a new movie from Mattel was announced.

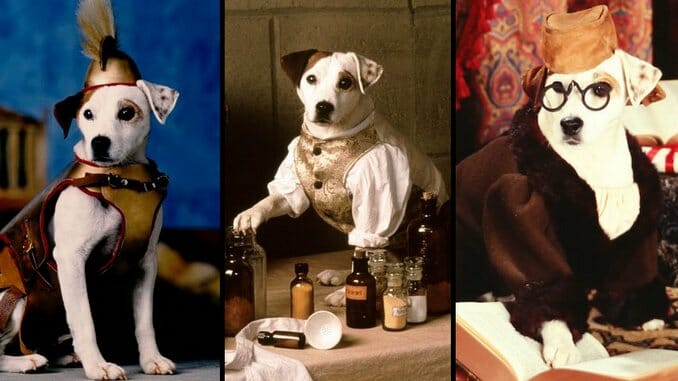

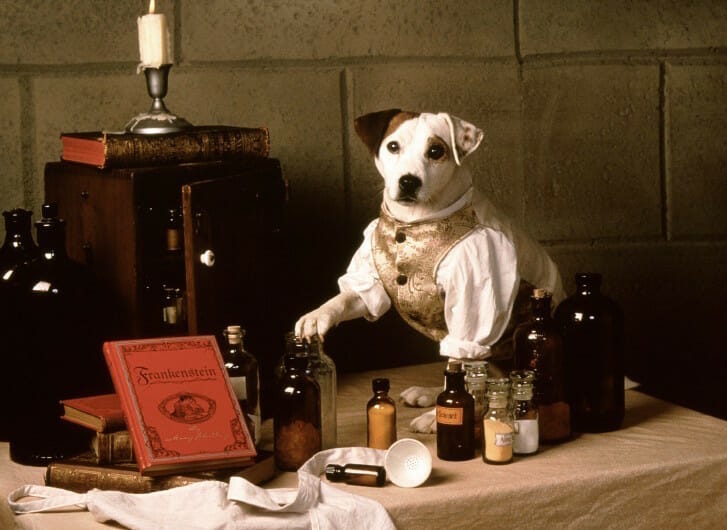

Publicity photos by Carol Kaelson, Courtesy Big Feats Entertainment TV Features Wishbone

In July, Mattel Films and Universal Pictures announced they will develop a movie based on the 1995-98 live-action PBS Kids series Wishbone—the tale of “a little dog with a big imagination” who pranced through classic literature—but fans who grew up on the show greeted the news with mixed reactions on social media.

While some are happy to get any new Wishbone, others raised an eyebrow that the film will be helmed by producer Peter Farrelly (Green Book, There’s Something About Mary) working from a script by Roy Parker (his biggest credit is an unproduced screenplay from the 2019 Black List). Of note, Universal/Mattel did not hire the original Wishbone team, who had recently pitched a new TV project for the on-screen pooch.

Joey Stewart, first assistant director on the original Wishbone initiated the idea for a reboot in 2015, suggesting to Wishbone producer Betty Buckley (not the Broadway star) that they should try to acquire the rights to the series from Mattel, which hadn’t done anything with Wishbone since acquiring the property in 2011.

“Joey and I put together an LLC,” Buckley says, though she told Stewart rebooting Wishbone would be a long shot. Nevertheless, Novel Tails LLC was born to revive Wishbone and develop additional children’s programming.

Buckley, currently a film instructor at Texas State University and an independent producer, approached Larry Brantley, the voice of Wishbone, and the original show’s head writer/supervising producer, Stephanie Simpson, about being involved.

“[Betty and Joey] wanted to do a reboot with me rebooting it because, to be honest, most of what the concept was did come from my head,” Simpson said in June. “We did go into the Mattel building a couple of times […] it feels like Wishbone is locked in the basement of Mattel and we can’t seem to get that dog out of the basement!”

Now even if Wishbone breaks out to appear on the big screen, the new production will likely lack the voices of those who endeared Wishbone to a generation.

![]()

What’s the Story, Wishbone?

Wishbone creator Rick Duffield was working at Lyrick Studios—the Allen, Texas, company that unleashed Barney & Friends in 1992—when he pitched Lyrick owner Dick Leach on a children’s series starring a dog.

“He liked the idea and said we’d probably end up at PBS because that’s where Barney was,” Duffield says. The team recruited Simpson, a New York playwright, to become the de facto head writer/showrunner.

“I came to Texas to help create the show and come up with the concept and write the pilot script and the show bible and pitch it to PBS,” she recalls. “When I came to write Wishbone I’d never written for television or movies. I’d written a play. I’d go to Borders and get a screenplay book and look at how [a screenplay] was formatted. I tell any young person, ‘Say yes on Friday and figure it out by Monday.’ That is the way to live your life in this business.”

The show’s concept featured Joe Talbot (Jordan Wall) and his single mom Ellen (Mary Chris Wall, no relation to Jordan) and their dog Wishbone, living in the town of Oakdale along with neighbor Wanda Gilmore (Angee Hughes) and Joe’s friends, Samantha Kepler (Christie Abbott) and David Barnes (Adam Springfield).

The Talbots’ contemporary adventures paralleled fantasy sequences in which Wishbone retold tales from Oliver Twist to Frankenstein. Buckley recalls the trip to Los Angeles for canine casting where producers met dogs from Look Who’s Talking Now! and Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey. But it was the last dog seen—a Jack Russell Terrier named Soccer and his trainer, Jackie Kaptan—who won the role of Wishbone thanks his ability to jump and back flip.

The team decided early on that viewers would hear Wishbone’s thoughts but that his lips would not move as if he was speaking. “Computer-generated effects were new [at the time] and very expensive,” Duffield says. “It’s what’s going on inside his head anyway.”

Actor Larry Brantley, who was 24 at the time, recalls going into his callback audition where Soccer had been working with other auditioning actors. Kaptan said the dog needed a break and she pulled out a tennis ball for Soccer to play with.

“For some reason I still can’t quite understand, I started verbalizing out loud what must be going through the dog’s head while he’s playing catch with himself,” Brantley recalls. “It must have gone on for two minutes.”

After the dog’s break Brantley grabbed his script and asked it the producers were ready.

“Oh no, that was the audition,” he recalls Buckley saying. “I thought, ‘I just blew this so hard.’ But ultimately that is I think what landed me the role, the ability to observe and just organically go there.”

Lyrick then pitched the show to then-PBS executives Alice Kahn and Kathy Quattrone. “They said, ‘We want this!’ in the room,” Duffield says, “but it took months trying to figure out what the deal might be and also because they were renegotiating Barney.”

The negotiations dragged on so long, Duffield says the Lyrick team decided to go ahead and make five episodes (Buckley recalls PBS ordered five episodes). Before those five were complete, PBS ordered a 40-episode first season from Big Feats Entertainment, a division of Lyrick.

“We were basically shooting two different shows at once,” Duffield says, noting the actors from the Oakdale scenes never showed up in the fantasy sequences, which were populated by a repertory of local actors.

Each episode was filmed over five days. Lyrick had soundstages as well as a backlot where the Wishbone crew filmed both the exteriors of Joe’s cul-de-sac and some fantasy scenes.

Brantley says he worked six days a week, reading Wishbone’s lines on set at the same time Soccer acted out a scene and then going into a recording studio on Saturday to record the dialogue. Brantley adlibbed when the dog made a motion that necessitated comment (for instance, if Soccer’s left ear stood up straight for no apparent reason) or to fill time if Soccer hit his mark slightly off-schedule.

“There was always room to play,” Brantley says. “That was a big thing with Rick.”

Mo Rocca joined the show’s writing team early in Season 1. Yes, that Mo Rocca, who is now a correspondent for CBS Sunday Morning, author (“Mobituaries: Great Lives Worth Reading”) and occasional actor (The Good Wife, The Good Fight). “It was my first job in television and it was storytelling boot camp,” Rocca says. “It’s the set of tools I go back to more than any other, the experience I draw from more than any other in my career.”

Wishbone received widespread critical praise upon its debut, winning four daytime Emmys, a Peabody Award (1998) and two Television Critics Association awards (1996 and 1997), including the second for a TV season in which Wishbone produced no new episodes (whoops).

The series was praised for staying true to the stories it retold, even when they involved some grown-up elements. In the “Joan of Arc” episode, Joan is still burned at the stake—the camera just pans away before she is engulfed. “Rick’s hard and fast rule was we don’t write down to kids,” Brantley says, “and we do not shy away from difficult subjects.”

Even in its day, Wishbone appealed beyond its target audience of children ages 6-12. Producers sent Brantley on a press tour where he encountered college kids and young married couples with no kids who were fans. “I remember meeting an entire retirement community in a suburb of Chicago,” he says. “They bused them in and they were all fans of the show. It was amazing to me.”

But Wishbone was an expensive program to make and efforts to renew the series for a second season were stymied, Duffield says, by politics.

“There was a great controversy at the time in Congress about how much money PBS was not making on ancillary [goods] from the production of their children’s shows and that’s what made the negotiations very difficult,” Duffield recalled.

Eventually PBS ordered a truncated, 10-episode second season. A separate deal resulted in a 90-minute movie for Showtime, Wishbone’s Dog Days of the West, featuring the same cast and filmed just after Season 2.

But the almost two-year gap where no new episodes debuted (from November 1995 to October 1997) hurt the show’s momentum. Plus, the kid actors aged noticeably. “It was a little awkward,” Duffield acknowledges. “We let them grow up a little bit and in Season 2 we added a couple of younger characters thinking that might pan out in the future.”

After the Showtime movie and Season 2, Wishbone pretty much died as a franchise.

“It was money,” Duffield says. “We just couldn’t finance it. PBS couldn’t come up with the money. We couldn’t come up with the money. It was a sad thing for lot of people.”

The way PBS rolled out Wishbone may have hurt the show, Buckley says. All 40 episodes of the first season of Wishbone aired over nine months between March and November 1995. Compare that to PBS’s 40-episode, first season roll out of “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood,” which spanned 15 months between September 2012 to February 2014. Season 2 of Wishbone aired October 1997 to April 1998, with the Showtime movie premiering in March 1998.

“We all wanted it to be on once a week to build our audience and not just blow all that content” in a condensed period of time, Buckley says. “The merchandising and marketing didn’t have time to catch up with the money spent for the show. […] But what happened was Barney was just a cash cow and [Lyrick] put all their eggs in that basket. They could tape a Barney episode in the studio much quicker and for a lot less money.”

![]()

Afterlife and Memification

Once production ceased on the Wishbone TV series, books based on the show continued to be published for several more years. Wishbone never received a licensed, complete series box set DVD release but a DVD set containing four episodes was released as late as 2011. Wishbone DVDs are not as plentiful as VHS tapes of individual episodes that abound on Ebay. (Stewart says he purchased a pirated version of the entire Wishbone series on DVD, complete with the PBS bug on screen.)

Currently the easiest way to watch Wishbone, which is not available on a subscription streaming service, is on YouTube, where someone has taken the time to post the full series (each episode has been cut into three segments).

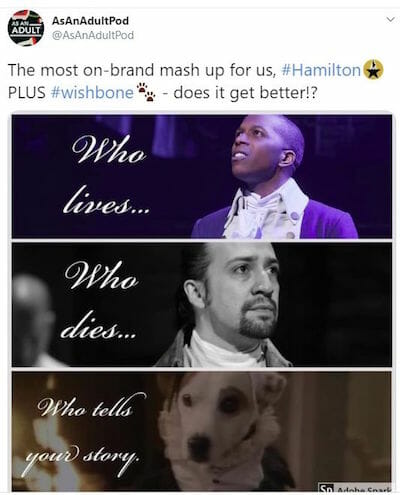

Even prior to Mattel Films’ July 2020 reboot announcement, Wishbone images proliferated on Twitter as memes of all sorts, from Hamilton to “Who wore it better?” to Paw Patrol comparisons:

Unauthorized merchandise is still sold online. Websites devoted to the show continue to provide background on the series. Kids who grew up on Wishbone still write about it.

“I used to have a Wishbone T-shirt and whenever I’d wear it, I’d have people come up to me with such intensity,” Rocca says. “It used to be parents saying it was the only show they’d let their kids watch, and then it was young adults. [In 2016] I was commencement speaker at Sarah Lawrence College and I was talking about my career and of all the things I’d done, [Wishbone] was the one that brought down the house. The love for the show, it makes me so happy.”

Duffield attributes the show’s cult following to affection for the anthropomorphizing of animals

“It’s playing with your mind and pretending there’s an intelligence in that little guy that’s big enough to inhabit the greatest stories of all time,” he says. “Kids resonated with it on that level. ‘I’m a small person and maybe my imagination is big enough, maybe I’m big enough to explore those big stories.’”

Simpson says she’s aware of the fandom, particularly as its 1990s-era viewers have become parents. “It just seems like a golden time to capitalize on that love,” she says. “Those ‘90s kids look very dated but the overall concept—what the dog does and how he relates to the world—is evergreen, and you can keep adapting it to whatever time you’re living in, which is a wonderful thing.”

![]()

Wishbone Rebooted?

Wishbone has been rehomed a lot over the last 20 years. In 2001, HIT Entertainment purchased Lyrick, including the rights to “Wishbone.” In 2005 British private equity firm Apax Partners bought HIT. In 2011, Apax sold HIT to Mattel.

And that is where Wishbone sat, trapped in Mattel’s basement.

Stewart and Buckley mounted their rescue mission, but series creator Duffield says he was uninterested.

“I feel like I spent all my ammo,” he said in June. “The way we did it really can’t be done again. It would have to be reinvented. You’d have to find a new dog and start over. It’s a very complex show to pull off in these lean and mean times.”

Although Soccer died in 2001, Buckley says she was in touch with animal trainer Brian Turi, who worked with Jackie Kaptan on the original series. “He’s found another dog, although who knows if it would be that dog,” Buckley says.

Stewart and Buckley recruited Brantley to record dialogue in Wishbone’s voice for a video presentation to Mattel Television executives, “sort of a personal plea to Mattel by Wishbone,” Brantley says, noting that while his voice has gone down an octave over the past 25 years, he can still capture what’s most important about the character.

“I don’t think what was signature about Wishbone was the voice as much as his attitude and his personality, and that’s never gone away from me,” Brantley says. “That spirit, that joie de vive that always existed in Wishbone, I’ve still got that. It’s amazing that it had not been beaten out of me.”

The Wishbone cast and crew stay in touch—there have been at least two reunions via Zoom since the pandemic began—and multiple crew members echoed Stewart’s reason for wanting to revisit the show: “It was the most rewarding thing we’ve all done in our careers and it felt like somebody needed to get it back.”

After Wishbone Simpson’s gone on to a busy children’s TV career, writing for PBS’s Arthur before becoming writer/producer on Arthur spin-off Postcards from Buster, Disney Channel’s The Octonauts and most recently Netflix’s Hilda. She now has a deal to create children’s programming for DreamWorks. Her idea for a TV Wishbone reboot involves expanding the stories beyond the Western canon, something the original series only rarely did (e.g. “Anansi the Spider” in “Bark that Bark;” a Native American story in “Dances with Dogs).

“It doesn’t have to be a story written by someone in the Western canon, although there are some great stories there, but it can also be a folk tale that’s been the foundation for an entire culture’s belief system,” Simpson says. “It can be a character that is part of a ritual that’s enacted every year in a specific place. It can be a poem. It can be a song. It’s a framework that is both flexible and continuously changing but also has a timeless quality to it.”

As for evolving the show’s lead character, Simpson said in June, “Perhaps it’s Wishbone’s child or grandpup who didn’t even know he had this amazing ability [to go into stories], the classic hero’s journey where you discover you’re Luke Pupwalker and then we’re off and running in a new Wishbone direction. I say all this because I’d love to do it, but I don’t think it’s going to happen.”

Buckley, undaunted, says revisiting Wishbone is more than just a business proposition.

“This is going to sound funny, but we all want to make the show because we loved it,” Buckley says. “People don’t really understand that. It was just so much fun. Obviously we would love to be involved in whatever they want to do.”

Emails to Mattel Entertainment press and Mattel head of global communications Dena Cook sent in June and early July before the movie announcement asking about the proposed Wishbone TV series were not returned.

“In the end we just weren’t able to make any headway with the Mattel people,” Simpson said in June. “There was talk they wanted to make some kind of Barney movie and then suddenly that they might want to make a Wishbone movie, which could also be great. But all of that is to say, they don’t have, as far as we can see, a plan really but they also don’t want to have to relinquish control.”

While Mattel’s July announcement suggests the original creative team won’t be making Wishbone content any time soon, movies die in development all the time, so perhaps Wishbone could bounce back to TV at some point. Mattel is just getting started on an ambitious slate of films based on Barbie, American Girl dolls, Hot Wheels and Masters of the Universe among others. So far none have come to fruition.

“[Mattel Films executive producer] Robbie Brenner put together the Barbie [movie] with high-powered people [including Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach] and the same with Barney [Get Out star Daniel Kaluuya is among the producers],” Buckley said a few days after the Mattel announcement blindsided the original Wishbone team. “She moves in those circles. To that extent, it’s quite a compliment. … but for me it’s bittersweet, primarily because there was just a magic and a joy from the team we put together in the making of it and it showed up on screen.”

If Mattel does produce a Wishbone movie, perhaps the original series will see the light of day via streaming on NBCUniversal-owned Peacock as an effort to promote the Mattel-Universal movie. And Buckley chooses to remain optimistic about possibilities down the road.

“I don’t necessarily think the movie means no series,” she says. “We were having conversations and they went dark. But it doesn’t mean the smaller dog can’t promote the bigger dog.”

Brantley says he has no expectation that he’ll be brought back to voice Wishbone; no one from Mattel Films has called so far, although the film’s writer did friend him on Facebook. Brantley was just happy to pick up 100 new Twitter followers on the day the film was announced.

“I have made my peace,” he says. “We created a thing that will live in the hearts and minds of people who have memories of it. And they’re still talking about it. We had that experience and now it’s time to let that go and let somebody else take up the mantle to do with it what they will. I’m pulling for them because if they get it right, they’re gonna know what that magic feels like. That’s something I wish there was a lot more of in this world today.”

Rob Owen is author of the book “Gen X TV: The Brady Bunch to Melrose Place,” a past president of the Television Critics Association, and veteran TV writer/critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. In the 1990s his mother taped Wishbone episodes off PBS on VHS tapes that his 10 and 6-year-old sons now watch. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook @RobOwenTV.

For all the latest TV news, reviews, lists and features, follow @Paste_TV.