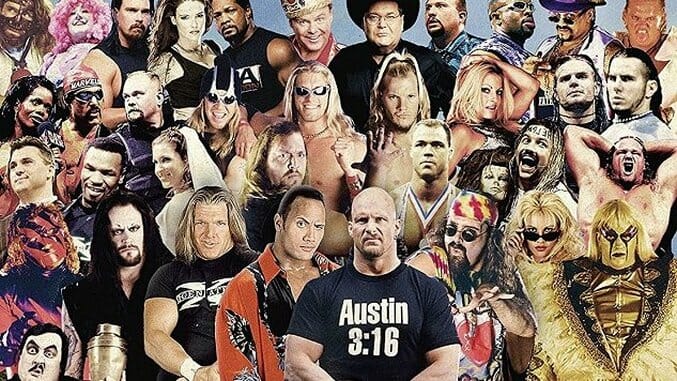

It’s a hallowed sentence, issued from the lips of smarks everywhere, adorning hundred-page forums and Reddit threads the Internet over for more than a decade now. Sure, it takes many forms: the inquisitive, the exclamatory, the exaggerated. It comes in response to almost any event—the return of an old favorite, a particularly brutal beatdown, or even the perceived tone of a throwaway promo. But it all boils down to one basic thought: when the fuck is the Attitude Era coming back?

The real answer, as most rational megafans recognize, is almost certainly never. While Vince McMahon and the rest of the creative staff behind the WWE of 2017 aren’t above invoking the ghosts of Attitude past in order to draw more eyeballs to the weekly shows, be it in the form of yet another pseudo-”screwjob” or other Russo-esque swervery, the zeitgeist zoomed past the likes of Limp Bizkit and three-minute evening gown matches a long time ago. Even faced with the gaping chasm between the anything-goes tenor of the late ‘90s and the more restrained culture of today, some fans still desperately yearn for that vanished sliver of years when wrestling fandom was more than just an easy punchline for your friends to resort to.

But while few can debate the as-yet-unprecedented commercial success of the spawn of the Monday Night Wars, the reputation of the Attitude Era as a golden age for creativity remains controversial, especially among aficionados of the squared circle. Simply put, it’s not at all clear that a shift towards what used to be called “adult-oriented” programming—while vanishingly improbable—would actually fix any of the prickly issues that continue to plague today’s version of the WWE.

Looking back today, the regrettable haircuts and ass-heavy histrionics of the Attitude Era seem as far from the flailing tube-men of kid-favorite contemporary wrestler Bayley’s entrance as one can possibly imagine. Of course, one could say the same thing about the Attitude Era itself, especially compared to the largely-dismal stretch that preceded it. As any hopeless wrestling dweeb will tell you—probably at a social gathering, with or without your consent—the WWF’s love affair with concussive chairshots and broken tables first came during the lowest ebb of Vince McMahon’s titanic empire, when arch-rival WCW’s innovative booking, top-notch production values and massive payroll forced McMahon to take a risk on a bold new direction, fueled largely by talent new to WWE and ideas lifted from ECW. But, when the resulting boom finally ran its course in late 2001, after fumbling for a new formula for the better part of a decade, in recent years WWE has revived the larger-than-life Hulk Hogan-branded superheroics that first catapulted the company above the other “territories” in the 1980s.

Thus, it’s important to recognize the Attitude Era for what it was—an aberration, a last-ditch attempt at relevance that happened to pay higher dividends than anybody could have imagined. And, to be sure, the modern WWE—in what the company tries to push as the “New Era”—could learn a bit from Attitude, especially its unpredictable, take-no-prisoners booking style. But you have to dig past fathoms of Jerry Springer-inspired grime and cardboard “AUSTIN 420:69” signs to even approach that.

Let’s face it: while prodigious wrestling skill rarely cripples a wrestler’s chances of making it past the midcard, it definitely doesn’t guarantee it either. Though there were a handful of names who managed to combine an appealing (read: raunchy and/or adolescent) gimmick with surprising in-ring ability, such as the towel-toting PG-13 porn star Val Venis, talented newcomers like D’Lo Brown languished in the lurch, saddled with unpopular character after unpopular character. (Compare that to today, when someone like “The Perfect 10” Tye Dillinger—as bland an idea as one can imagine—can “get over” largely on charisma and one simple, chant-friendly gimmick.)

With the once-prestigious Intercontinental Title being passed around like a bomb with a faulty fuse, with notable exceptions, most low-to-midcard matches in the early Attitude Era (‘98 to ‘99) are mostly forgettable clothesline-fests that replace ring psychology with taunting, bragging, and/or dad-dancing. Fans may remember the succession of scintillating main events between the Rock and Mick Foley from this stretch—including their classic “I Quit” match at Royal Rumble 1999, best known for making Foley’s daughter and wife cry on-camera (and sure to serve as exhibit 1 if any CTE lawsuits ever make it to trial)—but they probably don’t recall the not-so-epic clash between Goldust and The Godfather. Most people didn’t tune in for the wrestling, and it showed; simply put, as even a cursory re-watch shows, the average match quality in today’s WWE far exceeds that of most of the Attitude Era.

Indeed, nobody cared less about the actual grappling itself than head writer Vince Russo; no, he cared about sports entertainment, emphasis on the “entertainment.” And nobody could accuse Russo of having anything less than a truly egalitarian view of what exactly constituted said entertainment. Freed from the conventional bonds of reality, taste, and good sense, Russo’s product may have sang in the key of an ambulance siren and smelled like a half-eaten Big Mac, but it made the federation ungodly amounts of money. The Attitude style was fast and dirty: angles that made headlines, rankled parents, and kept casual viewers glued to the tube.

And while this produced some of the more memorable moments in the federation’s history, such as Stone Cold Steve Austin showering Vince McMahon and his goons in cheap beer, or Austin running over The Rock’s “brand new” luxury car with a monster truck with horns, when Russo missed, he missed hard. Some of these less fondly remembered storylines read like a litany of tropes mired in misogyny and racism—Mark Henry’s “Sexual Chocolate” gimmick, which was little more than a celebration of sexual harassment; multiple “domestic abuser” characters, including Jeff Jarrett and Mark Mero; and yes, even a fake on-screen miscarriage—at ringside, no less.

But even Russo’s less-vulgar efforts, while well-suited to Raw’s episodic television format, didn’t quite gel with the actual, you know, wrestling. In particular, his ardor for opposed multi-man stables like Shane McMahon’s “Corporation” and The Undertaker’s “Ministry,” when combined with his penchant for supernatural, Buffy-esque tomfoolery, produced some of the campiest plotlines the company has ever seen. (One example: The Undertaker kidnaps Vince McMahon’s daughter at Backlash 1999, leaving McMahon in hysterics. A little more than a month later, McMahon reveals that he engineered the whole scheme himself in order to get revenge on perennial foe Stone Cold Steve Austin. It makes even less sense than you might think.) While these massive feuds sounded good on paper, when it actually came time for Ministry member Mideon to face Corporation enforcer Big Bossman in a singles match, not even the hardest-of-hardcore fans could muster any fucks to give.

Even at its best, wrestling storytelling could hardly be called “coherent.” It is, after all, a glorified carnival. A pimp Death Valley Driver-ing a porn-star isn’t any more or less believable than a garbageman locking horns with a pig farmer, after all. Still, even by this rather generous standard, the characters of the Attitude Era rarely felt like they occupied the same universe, let alone the same company. Or, to put it more bluntly, when you have legitimate UFC strongman Ken Shamrock facing the embodiment of pure evil the Undertaker live on pay-per-view, it makes the wobbling strings and tattered seams that hold the show together a little too obvious.

To be sure, when the Attitude Era was firing on all cylinders, it produced some of the most compelling matches the WWF/E has ever seen. But, really, as the era wore on, that had less to do with its booking and direction and more to do with the surfeit of talent jumping ship from the declining WCW, like Chris Jericho and the late Eddie Guerrero. Even the barnburners of the era were rife with shenanigans, interference and unconscious referees—so-called “clean finishes” were few and far-between. (For example, Triple H and The Rock’s 2-out-of-3-falls match from Fully Loaded 1998 has no less than half-a-dozen interference spots and ends on a technicality. While it doesn’t ruin the match completely, it certainly doesn’t augment it.)

So, given all this, one must wonder: why do some of the lifelong die-hards still thirst for the days of Attitude, even as their heyday creeps further and further into the rear-view? While the lost cultural relevance that wrestling once enjoyed must certainly factor into the equation, for me, it doesn’t constitute it entirely. As a recently un-lapsed fan, WWE of 2017 is a head-and-shoulders above the product of five or even ten years ago, but even still, it very rarely surprises anyone—except perhaps the kids that make up a sizable portion of its audience. Now that the last of the Attitude stalwarts are finally shuffling their way off the stage, perhaps the company can start to build new stars and keep things interesting without playing for cheap nostalgia. It won’t be easy, but, thanks to the sure and steady march of Father Time, Vince McMahon and his army of producers will soon be left with no other choice.

Steven T. Wright has written for The Atlantic, Rolling Stone,

Vice and more, and can be found on Twitter @Pseudagonist.