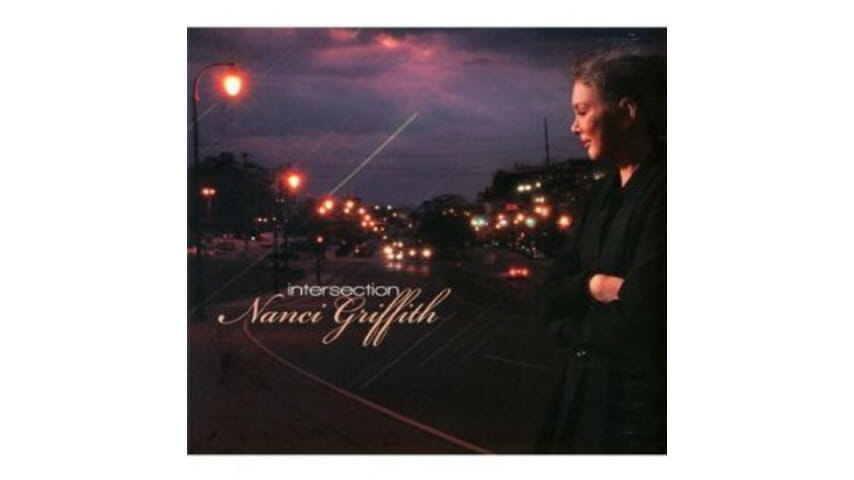

Nanci Griffith: Intersection

“I’m still gone and it’s all the same/ I’m taking notes and naming names…” snarls Nanci Griffith on the churlish, Pogues-evoking-the-Everlys “Hell No, I’m Not Alright” from Intersections, a more aggressive, full-frontal reckoning from the woman who was once the sugary-voiced sweetheart of Lone Star coffeehouses. If the little dresses and anklets were charming once upon a time, on Griffith’s 20th album, the fairytale is over.

Instead, she’s recorded a loose song cycle reflecting the corrosive nature of relationships, the loneliness one feels when it’s evident doubts and questions outstrip desired resolutions. Working with her lean road band of Pete Kennedy on all things stringed; Maura Kennedy on vocals, acoustic guitar and tambourine; and longtime compadre Pat McInerney on percussion and vocals, Griffith jettisons prettiness for the full force of reality coming down.

Opening with a few plucked acoustic guitar notes and her more expected choir-girl-after- a-pack-of-cigarettes voice, “Bethlehem Steel” paints a picture of a hooker growing old, walking the streets in front of the failed steel mill. Knowing the inevitable is what it is, to the point of making an uneasy peace with the cop who hassles her and knowing “Robert DeNiro will never run naked again/ in the streets of Bethlehem,” Griffith delivers a metaphor and an elegy for the state of the American way of life as known.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-