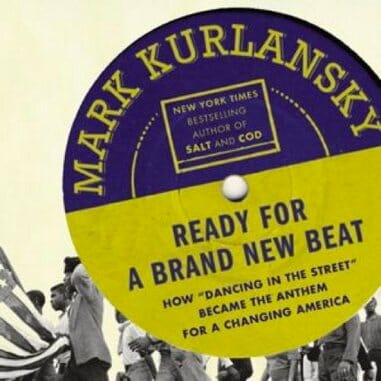

Ready for a Brand New Beat: How “Dancing in the Street” Became the Anthem for a Changing America by Mark Kurlansky

Callin’ out around the world

Books Reviews America

Many a popular song will purposely recall a bygone age or envision a future era—and try to transport listeners there. For the palpable pain of a bloody and turbulent historical period, think of The Band’s classic, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” which thrusts us back to the Civil War and the depredations visited on the South. For a haunting, unrelentingly grim conception of humanity’s as yet untraversed trajectory, try Zager and Evans’s psychedelic rock hit, “In the Year 2525 (Exordium and Terminus).” Interestingly, both songs came out in 1969, in the midst of social and political ferment in the United States.

Other records from the ’60s and ’70s were not meant to capture a specific past epoch, but do so quite naturally—perhaps unbeknown to their writers and performers. Doesn’t “Spirit in the Sky,” by Norman Greenbaum (who’s white and Jewish), sound as though it were a Negro spiritual—sung by slaves toiling in the sun-baked cotton fields—set to psychedelic rock music? The lyrics—“When I die and they lay me to rest, gonna go to the place that’s the best / When I lay me down to die, goin’ up to the spirit in the sky”—seem almost embarrassingly simple (masters often kept their slaves illiterate), and the message of rewards in the hereafter, while dovetailing with slave-owners’ desire to instill docility in people they intended to exploit for a lifetime, nevertheless recalls slaves’ legendary nurturing of self-resilience.

And then there’s “Midnight Train to Georgia,” immortalized by Gladys Knight and the Pips, who turned it into arguably the greatest soul number of all time. Most of us know it as the shattering tale of a star-struck Georgia man’s planned return home following his failure to realize his dreams in glitzy, pitiless Los Angeles. We hear the story related by his fiercely protective and self-sacrificing woman, who decides to accompany him. The physical journey undertaken by the protagonist, the crushing blow dealt his dreams, and even the irony of Knight’s powerhouse vocals affirming her subordinate role in the relationship combine to demand a deeper historical reading.

That chastened guy waiting forlornly at the L.A. station for the midnight train to Georgia inhabits a self-contained story revolving around his disillusionment and resigned acceptance of personal failure. He also embodies all the black men defeated by the Great Migration (broadly speaking, 1910-1970). Not everyone who left the Jim Crow South for a shot at dignity, economic opportunity, and the fulfillment of their dreams stuck it out in Chicago, Detroit, New York City, Los Angeles, and elsewhere. Many faced the same hardships of racism and unemployment, without the (meager) comforts of home.

Some men made the humiliating decision to cut their losses—“And he even sold his old car” bellows Knight achingly of her beau—and they headed back south. (In the song, Knight memorably decides to accompany her man to Georgia even though she calls L.A. home: “I’d rather live in his world / Than live without him, in mine.”) Intriguingly, Jim Weatherly (who’s white) wrote and performed the song as “Midnight Plane to Houston” before giving it to the aptly named Cissy Houston, who nonetheless changed the title/refrain and the protagonist’s gender for her version, which Gladys Knight and the Pips subsequently forever eclipsed with their own. “Midnight Train to Georgia” was not intended as a dirge in honor of the failed Great Migrants, but that doesn’t make it a less fitting one.

Now…what of those songs that a socially aware public associated with events that occurred after their release, taking advantage of the lyrics’ amenability to adaptation?

Mark Kurlansky (author of nonfiction bestsellers Salt and Cod, as well as the delightfully piquant The Basque History of the World) takes on one such song, the Motown sensation “Dancing in the Street,” by Martha and the Vandellas, in Ready for a Brand New Beat. His heady and edifying book chronicles the unlikely transformation of an innocent—almost frivolous—pop hit into a political protest song, and even a subversive appeal for mass violence, as disaffected African-Americans and their white comrades improbably wedded it to social activism and black civil rights.

The author treads a long and winding route. Though a brief introduction familiarizes readers with the song and Martha Reeves, Kurlansky then drops the subject in favor of a historical account of popular music, race relations and the rise of the Motown record label in Detroit. By the time he has progressed to 1964 and finally delves into the song again, we’ve read half the book. This painstaking approach, governed by a historian’s desire to situate his subject within its proper socio-historical framework, feels unfocused and often taxing, laden as it is with information concerning everything from rock ’n’ roll’s debt to African-American culture to Motown founder Berry Gordy’s upbringing.

The good news? Though reproducing (in his own words) widely covered material about the Civil Rights Movement and crossover music, Kurlansky ensures that by the time he plunges into “Dancing in the Street,” the song is surrounded by the socio-political forces roiling 1960s America. These include voter registration drives for blacks and Freedom Rides defying segregation in the South, black urban discontent in northern cities, Motown records’ increased popularity with white audiences (one of Gordy’s chief goals), and the United States’ growing involvement in the Vietnam conflict.

Penned by William “Mickey” Stevenson, Ivy Jo Hunter, and the up-and-coming Marvin Gaye, “Dancing in the Street” was originally intended for Kim Weston (Stevenson’s then-wife). Instead, it went to Martha Reeves, on the strength of a demo. Motown called in the Vandellas to add backup vocals—Martha and the Vandellas had already notched a few solid hits, including “Heat Wave”—and then the label released the song on July 31, 1964. It rose slowly but steadily on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart, peaking at No. 2 on Oct. 17. In the next few years, as civil rights activists endowed “Dancing” with socio-political meaning, and riots broke out in cities’ black neighborhoods summer after summer, the song registered a far greater (and unexpected) impact.

“Callin’ out around the world: Are you ready for a brand new beat? / Summer’s here and the time is right, for dancin’ in the street.”

Not an obvious choice to accompany a political protest of any kind. Still, who’s to say what the dancing’s about? Here’s how Rolland Snellings of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”), a civil rights group consisting of college students, explained the popularity of the song with young blacks: “[T]hey are moving to the rhythms of a New Song, a New Sound: dancing in the streets to a Universal Dream that haunts their wretched nights: they dream of freedom!”

Riffing off Snellings, Kurlansky encapsulates the observations of other contemporaries, including those who gave the song a harder, more violent edge, one informed by the riots that broke out in black urban neighborhoods (including those of Detroit), most famously in 1967 and ’68. The author writes, “And then there is that telling phrase: ‘Summer’s here and the time is right.’ And did not ‘calling out around the world’ mean a call for revolution, and didn’t the song include a list of cities, each with important black communities that were likely to have ‘disorders’?”

That list of cities goes like this: “They’re dancin’ in Chicago / Down in New Orleans / Up in New York City.” Later, it continues with: “Philadelphia, PA / Baltimore and D.C., now / Can’t forget the Motor City.”

When you consider that the writers and original lead performer of “Dancing” (many artists have since covered it) nowhere endorse a remotely political exegesis of the lyrics, and that Motown shied away from anti-establishment messages, the notion that it’s a protest song—and even a call to arms—seems flimsy. Co-writers Stevenson and Hunter, singer Reeves, and other figures Kurlansky interviewed for this book attribute no such motive to their song.

Neither did co-writer Marvin Gaye, who died in 1984. Gaye obviously couldn’t provide any recollections for this book, but Kurlansky nevertheless flirts with the idea that the singer/songwriter engaged in “masking” of the kind slaves employed in some of their spirituals (to provide information on escape routes), and recalls that in African music one finds “the idea that a political message could come simply from the nature of the sound.”

This feels fanciful. Lyrics are one thing, but try as you might, you can’t sustain the argument that any piece of music is inherently political. When it comes to the lyrics in this instance, no evidence of masking on Gaye’s part exists, and he didn’t reveal any hidden messages in the 20 years between the song’s release and his death. In fact, Kurlansky cites an interview with Gaye in which the artist recalls that, following the Watts, L.A. riots of 1965 (a year after the release of “Dancing”), he felt guilty about “all the bullshit songs I’d been singing” (and presumably writing) and lamented: “Why didn’t our music have anything to do with this?” (Unfortunately, although Kurlansky provides a bibliography at the end of the book, he often fails to link the excerpts he culls from others’ work to specific bibliographic entries. He leaves it to the reader to try to connect them. He also doesn’t provide documentation for interviews he conducted.)

Kurlansky also notes that “Martha Reeves argues that the politically charged word is streets, and that people who have the political interpretation often incorrectly call the song ‘Dancing in the Streets.’” Nevertheless, as the author adds shortly thereafter, there remains some confusion on this score. “In the recording, Martha tends to sing ‘street,’ but the backup singers reply, ‘Dancing in the Streets,’ so that there appears to be a dialogue between these two ideas.”

Over and above this debate, we mustn’t forget that just as the writers and performers of a song cannot force audiences to enjoy it, neither should they presume to dictate the interpretation of its lyrics, a point Kurlansky rightly emphasizes. Viewed within the context of mid-to-late 1960s America, the lyrics of “Dancing” do lend themselves—albeit shyly—to a political interpretation. For example, the poet and historian of black music Amiri Baraka, interviewed by Kurlansky, explains that the song hit the airwaves simultaneously with the outbreak of what he pointedly terms the Harlem, NYC “rebellion” of ’64. But there was more to come. Kurlansky quotes Baraka making the case that, since we now know that further riots erupted over the following few years, the song can be said to have “prophesied the rebellion” that engulfed cities across the country. The author spells out Baraka’s observation: “After all, the lyrics are mostly in the future tense— ‘There’ll be …’”

The response to “Dancing” by politically minded folks—such as the more militant segments of SNCC—carries another distinction worthy of attention. They took to the lyrics in their entirety. This contrasts with other songs that suddenly receive a new lease on life due to a perceived symbiosis with the times. When listeners invest such songs with socio-political meaning, the endeavor rarely proves so extensive in scope. People may hold aloft a stray verse or lyric as the quintessence of the Zeitgeist. Most else falls by the wayside.

“I was educated at Woodstock / When I start lovin’, oh I can’t stop.” That’s from “Soul Man,” by Sam & Dave. The song came out in 1967; Woodstock referred to a high-school in Memphis, Tenn. Two years later, following the outdoor music festival of the same name held in upstate New York, the meaning changed forever. The lyric in question jibed perfectly with the free love theme of the concert and its era, though the other parts of the song did not assume greater relevance.

Consider, also, a quixotic old blues song that now cries out for renewed consideration—to little avail—thanks to a single verse. On Jan. 20, 2009, when Barack Obama became the first black president of the United States, few people harked back to Big Bill Broonzy’s “Just a Dream No. 2” (1939), despite the African-American guitarist’s singing: “I dreamed I was in the White House, sittin’ in the president’s chair.” You could easily interpret Broonzy’s words to mean that he’s imagining a burned-out president eagerly handing him the reins of leadership: “I dreamed he shaked my hand, said ‘Bill, I’m glad you here’ / But that was just a dream, just a dream I had on my mind / Now then when I woke up, baby, not a chair could I find.” The rest of the song, in which Broonzy recounts his other flights of fancy, has nothing to do with the presidency.

“Dancing in the Street” falls into a class of its own, what with civil rights activists’ wholesale lyric grab. Rarely, if ever, do independent-minded people—let alone headstrong social revolutionaries—acknowledge that a work of art that coincided with their arrival on the public scene actually sums up their message just as well or better than they could have. In this case, those enthralled by the lyrics cherished the added bonus of the music, which they considered an indispensable complement to the words.

“Motown did not do many brass introductions,” Kurlansky points out, referring to the trumpet fanfare that follows on the heels of the drum and bass combination opening the song. “But there were other unusual characteristics to the track.” Paul Riser, who arranged the music, not only brought in trumpeters Johnny Trudell and Floyd Jones; he elicited a stellar performance by legendary Motown session band The Funk Brothers. Kurlansky draws the reader’s attention to Benny Benjamin’s unique drumming style, James Jamerson’s syncopation on bass guitar, and the oft-praised bridge, when the music segues into a minor key.

All this meant that, unlike the politically conscious folk music of the era (sung mostly by white artists), or Sam Cooke’s ballad of hope-tinged-with-sorrow “A Change is Gonna Come” (which became a Civil Rights Movement standard), the new Martha and the Vandellas number made you want to get up and move your body. Songs that explicitly called for political action and simultaneously featured an up-tempo beat (such as “We’re a Winner,” by The Impressions) had yet to come out.

In short, “Dancing in the Street” galvanized people on more than one level. The reaction by the young, black and revolutionary serves as a profound testament to the lyrical flexibility of the song as well as its infectious melody. Paradoxically, “Dancing” prompted many African-American listeners to cut loose…even as it strengthened their resolve to fight for usurped rights.

Unfortunately, though perhaps inevitably, some went so far as riotin’ in the streets.

Rayyan Al-Shawaf is a writer and book critic in Beirut, Lebanon.