Here Comes the Night by Joel Selvin

The Dark Soul of Bert Berns and the Dirty Business of Rhythm & Blues

Every so often, a music bio arrives that becomes “the book to read.” Think of Last Train To Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley and Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley, Peter Guralnick’s exhaustive considerations on the arc and impact of rock’s first true superstar. Last year gave us Johnny Cash: A Life, Robert Hilburn’s deeply lived and reported recounting of the Man in Black. Books like these, defining what lives and careers really mean, engage readers well beyond the realm of music bios.

It’s a tricky line to walk. The author must balance the deep insights and minutiae the invested music lover expects with a story that draws those who have little interest in who played what instrument on what album, or when a certain record came out. Writing that reaches further, creating connections with the culture at large and offering a mandate about what these lives say about America in the moment, elevates truly great books no matter what subjects they capture.

Joel Selvin’s new book makes a claim to greatness. In the world of glaringly and exhaustively over-examined star bios, the San Francisco-based journalist not only exhumes a lost soul in the pantheon of ‘60s pop and soul (along with capturing rock ‘n’ roll’s burgeoning eruption), he also creates as engaged and energetic a narrative as any so-called serious writing can contain.

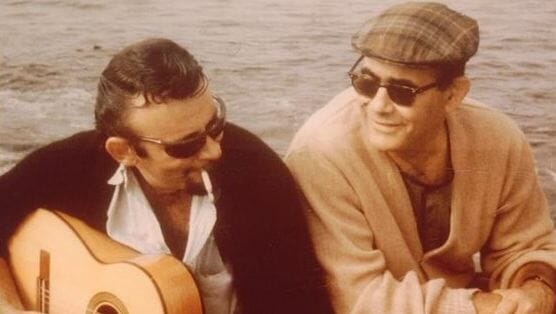

Selvin’s subject: Bert Berns. Born to Russian Orthodox Jewish parents in the Bronx, Berns contracted rheumatic fever at a young age. It left him with a compromised heart, yet that hardly slowed him. With a doting mother and a hunger for nightlife, for love and for rhythms that made people dance, he started hustling the Brill Building in no time, making records and trying to find a place at the table in a wildly shifting record business.

In many ways, the man remains only a footnote, but Berns’ songs and productions are legend. He wrote or co-wrote “Twist & Shout,” “Hang on Sloopy,” “Piece of My Heart,” “Everybody Needs Somebody To Love,” “Here Comes the Night” and “I Want Candy.” He produced Solomon Burke, the Drifters, the Isley Brothers, Erma Franklin, Neil Diamond, Lulu, Them (and later its lead singer, Van Morrison), and we find his fingerprints on the iconic recordings of these artists, including standards like “Cry To Me,” “Under the Boardwalk,” “Baby Please Don’t Go,” “Cherry Cherry” and “Brown Eyed Girl.”

Berns worked at the same time as Rock and Roll Hall of Fame songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Motown’s Brian Holland-Lamont Dozier-Eddie Holland, uber-producer Phil Spector and Atlantic Records founders Gerry Wexler, Ahmet Ertegun and Nesuhi Ertegun. Even among these immortals, Berns’ ability to throw himself over a cliff in the name of a song, a star or a moment gave him a brio all his own. He died of heart failure at 38, a perfect rock ‘n’ roll ending that truncated the legacy-polishing that comes with time. Those who remained took—or obscured—credit for too much of his work.

Hands-down the most outlandish persona in a business of brimming with outlandish characters, Berns, as Selvin renders him, became the brilliant loser who harnessed lightning and churned it into platinum, betting it all on one act or another.

Selvin’s vibrant language ripples with immediacy, whether he describes Cuba before Castro, Mafia bosses like Carmine “Wassel” DeNoia’s investment in “the music business” or the way actual songs emerge from your radio. The San Francisco Chronicle’s music critic from 1972-2009, Selvin knows the machinations of the music business and understands the artists who make it. Beyond the story of a life, Selvin paints an insightful picture of how music business gets done. He perceives the circuitous routes through politics, drug problems, greed, personal life snafus and rampant egos that most people don’t realize can come between a tune in someone’s head and a record that person loves.

Selvin tells of rock ‘n’ roll’s birth and how the golden age of rhythm and blues flared to life, of rules written and rewritten. Sharp guys with an eye on the prize could suddenly not just get in the game, but rule it. Berns gripped the new reality with a vengeance. From wannabe to indie hitmaker, he kept pushing, striving, but especially creating. His street-corner romanticism mainlined a vein broad enough to briefly make him the toast of New York City’s night club/Brill Building scene.

AM radio drew young America, offering a compelling world of old-school glamour, wise guys, bouffant hair … and music so sweet. Berns, the outsider, got into Atlantic Records as a staff producer. Later, he teamed with the Erteguns and Wexler to create Bang! Records. His label heated up with the McCoys, the Strangeloves and Them (featuring that young Van Morrison, who would also record for Berns’ label on his own).

Selvin captures the appetites of the power players, as well as their vulnerabilities and blind spots, and he somehow manages to tease a seamless tale from a bottomless catalogue of sources. He eschews the gossipy showbiz tone embraced by many pop culture chroniclers. Instead, he traces the works of iconic names (Leiber and Stoller, for example) from songwriters to publishers to label owners. When he explains the demise of these artists, we feel compassion more than sensation.