Far Cry Primal: Make This Village Great Again

When we write about the past we’re always writing about the present. That writing can take a personal tone, showing how a person got to the place that they are through the person that they’ve been. Ben Carson stabs a guy and runs for President of these United States. Jessa Crispin runs away from those same States and into a cavalcade of experiences across Europe. Everyone has to make it through time in order to get to where we are, and we shape the contours of that story in order to ground our current lives.

The writing can also take a cultural form. The stories take the same shape as the personal ones, but the stakes become higher and broader. This is the realm of Manifest Destiny and the triumph of American ingenuity. This is where we learn that we have to make America great again, like all we need to do is dive into the pool of the past to grab the pearls of a long-gone triumph.

If the edges of what I’m saying here feel horrifying, you’re getting the right feeling. Telling stories about the past is not just political, it is politics itself. To say anything about origination points is to say something about where we are and where we can go. Setting the terms of the past sets the terms of the present, and that’s what bothers me about Far Cry Primal.

Up front, I enjoy playing Far Cry Primal. It has the mind-numbing quality of checking things off a list or comparing rows in an Excel spreadsheet, and I while that sounds like a back-handed compliment, I don’t mean it that way. I’m a longtime critic of concepts like “flow” or “immersion” because I never feel enveloped by a game in the way that those terms seem to require, but I would be lying if I said that Primal doesn’t get me a significant amount of the way there. Walk forward, pick a reed, pick up a rock, defend yourself from a wild dog, pick up a green leaf, free a fellow tribesman, and do the same over and over again until you wind up at the arbitrary destination you highlighted on the map five minutes ago.

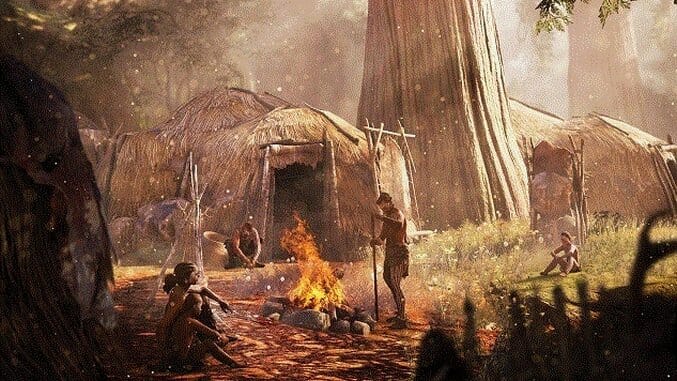

That process of collection is part of the immersion. In good Ubisoft fashion, Primal is full of things that the player can collect so that the player can upgrade both herself and the world around her. In this specific context, there are two things to be created: equipment and huts. The former makes you more effective in the world of Primal, and the latter, well, sort of does the same thing by unlocking more things that you can upgrade yourself with.

While these are both so-standard-as-to-be-boring mechanical systems, they are also stories about humanity. The Far Cry franchise, maybe more than any other, has stressed that its stories are full of important statements about the human condition, from Far Cry 2’s sophisticated critique of interventionism to the less-well-guided but no less seriously-attempted colonial narratives of Far Cry 3 and 4. These games are trying to say something, no matter how far short of the mark that those stories have fallen, and Primal is doing the same despite its taking place in the far-flung past.

Ubisoft has a strange relationship with real history. The Assassin’s Creed franchise plays fast and loose with figures and events in order to get the most amount of play out of their “history is our playground” slogan. However, at the same time, the cathedrals, ships and palaces of those games are always intricately matched to those appearing in real life. There’s a real wax and wane to what gets taken up as serious and important within the corporate philosophy of real life adapted into play, and Primal is no different. This game features a reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European language and puts all linguistic communication within that language in order to drive a story about the past. History might not be a playground in this franchise, but it is a place to experiment and play games.

What are the stakes of that experimentation? What are the stakes of mixing speculative historical details with tried-and-true Ubisoft mechanics? If telling a story about the past is really telling a story about the present, then what kind of present does Primal’s 10,000 BC story give us?