This article discusses plot points from the entire game.

There’s nothing that brings someone into their own head as thoroughly as spending time alone in the woods. We have plenty of fiction about this, of course. The world is full of stories about hermit mystics, society drop-outs and nature-worshipping romantics. As a people, we’ve always been obsessed with the idea that a retreat into the wilderness can bring us more in touch with ourselves—that isolating from the rest of civilization can reveal deeper truths about the world we live in. Whether there’s truth to this sentiment or not hardly seems to matter. The idea endures, and it’s the basis for Campo Santo’s Firewatch, a videogame where the isolation of nature is used to examine the ways in which we relate to others.

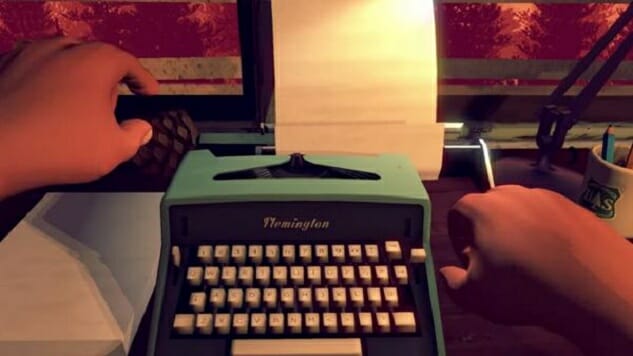

Henry, Firewatch’s protagonist, has taken a job as a lookout at Wyoming’s Shoshone National Park, a sprawling wilderness of dense woods, dramatic cliffs and placid lakes. Henry comes to Shoshone to get away from the difficulties of his personal life. His wife’s worsening dementia is wearing on him, heightening a midlife crisis that he can’t seem to solve. Henry, like so many fictional figures before him, runs from his problems, hoping to find answers (or at least some sort of solace) in the wilderness.

It isn’t long before the romanticism of his retreat breaks down. Fellow lookout Delilah radios him, bringing a shred of humanity to a place otherwise detached from civilization. At first, they talk about the job. Before long their relationship becomes more personal, the two loners keeping each other company by chatting about pretty much anything that pops into their heads.

Henry and Delilah’s conversations are the backbone of the game. The player guides Henry’s side of their dialogue, choosing from a list of prompts that don’t necessarily affect the story, but instead inform how Henry develops as a character in the audience’s mind. As in a game like Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero, the plot’s foundation is inflexible. The player’s role in the narrative is to color in their version of Henry by interpreting how he would respond to various situations. When Delilah asks why he’s taken the lonely job of a fire lookout, it’s up to the audience to decide if Henry is the type to spill his troubles to a virtual stranger, take offense to her probing or shift the conversation in a new direction entirely.

It’s hard to notice how effectively Firewatch’s narrative themes and degree of player interaction mesh until later in the game. As the plot unfolds, it reveals itself as a story about the distance between who a person considers themselves to be and how others view them. This is most dramatically illustrated though the game’s central mystery. Henry and Delilah, noticing that they’re being followed and monitored by an unseen force, eventually realize that they’re the subject of a cover-up orchestrated by a man who accidentally caused his son’s death. Ned, an outdoorsman hoping to connect further with his son Brian, believes he can make his physically unadventurous boy become tougher—more like him—if he pushes him to go rock climbing and spelunking. Brian, thinking his father is too harsh and distant to listen to his feelings, tries to escape from him, ultimately falling to his death while trying to hide. Neither father nor son fully internalize the other’s position. Instead, they project their versions of the other person onto their relationship. Their failure to fully empathize with one another leads to the game’s grand tragedy. Isolated in their own worlds, imagining one another to be something they aren’t, a father loses a son and a son loses his life.

The theme of projection comes up again and again in Firewatch. As close as the player—and Henry—comes to feel to Delilah, she’s never a real, tangible presence. She’s a voice coming through the radio, represented only by the other lookout tower looming on the horizon. Even when Henry enters her tower in the game’s final moments, at long last entering the living space of someone he imagines he’s come to know intimately, Delilah’s physical presence is indicated only by how she’s decorated her tower and a single one of her shirts hanging on a clothesline.

Henry’s relationship to his wife Julia is characterized, too, by detachment. Their backstory is filled out by the player picking either/or options during an opening text sequence that details their meeting, marriage and Julia’s heartbreaking descent into early-onset dementia. The player constructs Henry’s reaction to his own life by choosing how they see him responding to this situation. Is he the kind of person who enjoyed going out drinking by himself as Julia’s illness progresses in an effort to cope? Or was he wracked with guilt every time he left her side?

Even the game’s perspective—the player looks through Henry’s eyes, seeing only his arms and legs as he traverses the park—is at a remove. We see his face through a single photo kept on his lookout desk, but we’re left to imagine his expressions and the way he carries himself. This distance is furthered in a scene where Delilah asks Henry what he looks like. The player chooses how Henry details his appearance so his friend can sketch a picture of him informed not by reality, but self-description. We project our version of Henry, who passes it along to Delilah, who makes it manifest in a drawing.

None of the cast truly know one another. Isolated as they all are—from one another; from civilization—they construct versions of each other based on the scraps of information they collect through dialogue and hazy impressions. Ned resembles a crazed murderer from a distance. Delilah becomes by turns either untrustworthy or idealistically supportive. Even Henry, Firewatch’s player-controlled avatar, only takes shape as the audience projects their version of his personality onto his dialogue choices.

The player only sees other people three times throughout the game. The first is the silhouette of two young women, far off in a lake. The second is Brian’s corpse, lying seemingly forgotten in a cave. The third is in the final moment of the game, when a rescue helicopter pilot comes clearly into view, extending his hand to pull Henry up into the craft—and return him to civilization. Otherwise, Firewatch is a game of separation and imagination. It’s startling when the player comes across other human beings. Seeing them is a reminder of how concrete another person can be, whether barely visible, dead or as a strong grip pulling us back into society.

These moments show that the rest of the world is always nearby. They interrupt the idea that we can simply refuse to handle personal trauma by retreating into seclusion. The game’s cast is a cautionary tale of what happens when we run from our problems, attempting to build a new reality rather than confront the one we’re forced to live with. The wilderness has always acted as the perfect space for this. It’s always been idealized as a blank slate in which it’s possible to start again. What Firewatch ultimately suggests, though, is that there is nowhere, no matter how remote, that isn’t connected to humanity—because we are human. It puts pressure on the idea that wilderness or isolation allows us to learn profound truths about ourselves, suggesting instead that who we are is a process of mutual recognition. We may be isolated within our own heads, but our identities are collaborative.

Reid McCarter is a writer and editor based in Toronto whose work has appeared at Kill Screen, VICE and Playboy. He is the co-editor of SHOOTER (a compilation of critical essays on the shooter genre), co-hosts the Bullet Points podcast and tweets @reidmccarter.