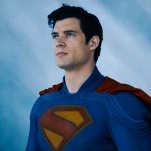

Andy Serkis: Hollywood’s Genius Shapeshifter

The Performance Capture Master on the Blurred Lines Between Games and Movies

Photos courtesy of Getty ImagesAndy Serkis is living proof that the oft-spewed “jack of all trades, master of none” theory is complete and utter bullshit.

Since his seminal performance as Gollum in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy in the early 2000s, the classically trained stage performer has forged several thriving careers not just as a specialist actor, but as a director and producer of high-concept film and theater built around what he refers to as “next generation storytelling.” Instead of pushing back, he’s fully embraced and expanded on being relegated to the role of “the motion capture guy.”

It’s here, when you invoke the now-familiar term “motion capture,” that Serkis will gently correct you.

“We say ‘performance capture,’ not ‘motion capture’ anymore,” he tells me at the Chateau Marmont ahead of the November 21 release of the Planet of the Apes: The Last Frontier videogame, which he produced. Take notes—it’s performance capture, not motion capture—kind of like when a comedian stresses that it’s not a skit, it’s a sketch. “With performance capture, the whole performance is caught with the emotion and audio and facial expressions in real time.”

Sure, this is a relatively small clarification, but the better part of Serkis’s last twenty years have been spent making them to a general public that still hasn’t quite embraced performance capture for what it is—an incredible tool, not a vehicle for spectacle.

While producing The Last Frontier is his latest venture, the past ten years has demonstrated that Serkis has become a jack of many, many trades with a common vision. Consequently, he gets to ask the questions that no one in Hollywood is qualified to ask, my favorite of which is “How does a tiger really behave, Benedict Cumberbatch?”

That’s right—the artist formerly known as Sherlock is playing Bengal tiger Shere Khan in Serkis’s upcoming adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book, slated for a 2018 release.

“Ours is not a spectacle,” he says of the film. “It’s a drama with actors as animals.”

It’s an ambitious creative vision to helm, but speaks to Serkis’s larger mission in the midst of what seems to be an endless stream of high-profile projects. The last half-year alone has found the English jack-of-all-trades in a leading (hopefully Oscar-recognized) role in War for the Planet of the Apes, directed his first narrative film Breathe starring Andrew Garfield and Claire Foy, has upcoming appearances as Supreme Leader Snoke in Star Wars: The Last Jedi and a major role as classic Marvel villain Klaw in next year’s Black Panther. This string of high-profile projects all leads up to Serkis’s Jungle Book, which he produced and directed with a fully performance captured A-list cast, appearing himself as Baloo. The only major role that Serkis hasn’t tackled yet is writing the source material itself, seeming to remain focused on adapting new technology to recognizable characters and themes.

It follows, then, that Serkis is the ideal candidate to adapt the world of Planet of the Apes from its filmic universe to a small-screen videogame—he’s built a whole career and philosophy built on the concept of thoughtful adaptation, whether it be adapting classic acting to work in performance capture or adapting a big-budget movie to a videogame that relies on individual experience.

It’s a lot, to say the least, but to talk to Andy Serkis about any of his projects is to talk to him about all of them—as the Serkis universe has expanded, its core values have remained firm.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-