Irritum (PC/Mac/Linux)

As you reach the dizzying apex of a particularly challenging level in Nick Padgett’s puzzle-platformer Irritum, a mysterious winged figure named Cassus issues this sobering reminder: “Obstacles do not make you stronger in this place. They all take their toll.” It is a well-timed piece of dialogue: When I first read it, I wanted to give up.

Videogames often perpetuate the myth that strength is a renewable resource. Riddled with bullets? Just take a break behind this wall and you’ll be fine! Burned alive in a helicopter explosion? For just five thousand dollars, you can be back on your feet in no time. Enemies are made to be defeated. Obstacles are built to be overcome.

In some ways, there is no theme more antithetical to the videogame than suicide but that is precisely the subject matter that Padgett explores in Irritum: The game is set in limbo in the immediate aftermath of an attempt on your own life. Irritum is a game about death and the pain of remembering. It wants you to feel lost, confused, alone, unrewarded. This is a far cry from jumping on goombas.

Typically, games that subvert our fantasies of invincibility adopt a survival horror format, forcing us to feel our own finitude through mechanics like health limitation and resource management. But Padgett has chosen the 3D puzzle-platformer as his form and created the closest thing to a survival horror platformer I’ve ever played: a survival horror platformer about the horror of surviving.

Unlike games like Deadlight or I Am Alive—both of which make claims to the hybrid genre of survival horror platformer—Irritum produces its feeling of finitude through conventional platforming mechanics themselves rather than importing common design tropes from survival horror action games. Neither does its horror come in the form of sheer difficulty; Irritum is challenging, to be sure, but it is no “masocore” platformer in the vein of N+ or Super Meat Boy. Its difficulty is designed to be endured, not overcome.

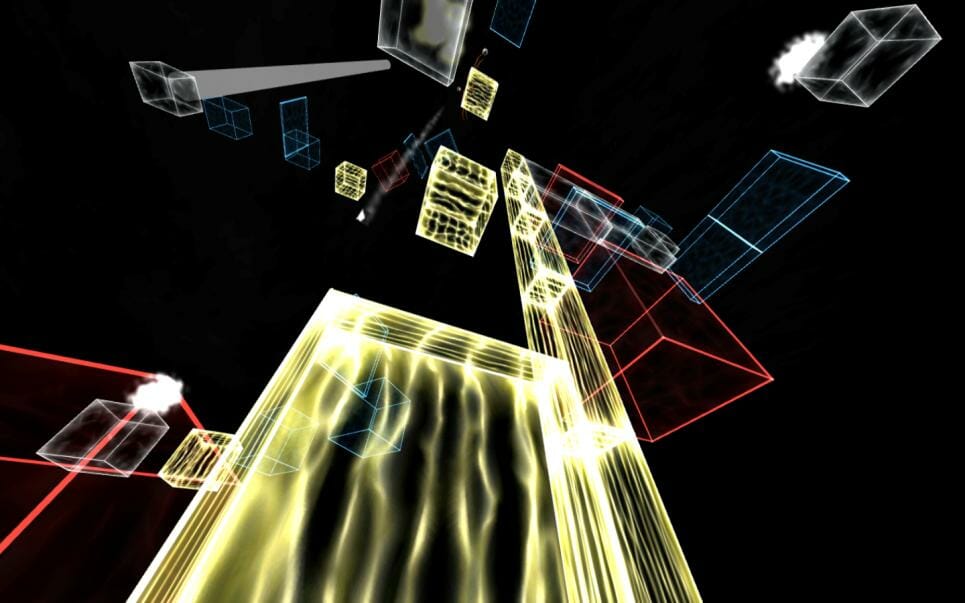

The horror of Irritum is a mechanical one, a slow suspenseful build-up followed by a sudden complexity. The game begins straightforwardly. Using the mouse buttons, you can choose which of three sets of platforms will be solid at any given time: red, yellow or blue. By switching back and forth between the different colors, you can traverse brief levels that are impossibly suspended above a murky river.

The levels, like memories, are blurry, impressionistic, even beautiful from a distance, but jagged and painful up close. As you traverse their impossible geometry, two shadowy angels—or are they demons?—named Sollus and Cassus offer guidance and confusion in equal measure. The world is featureless and abstract; the bright, primary colors of the platforms do little to offset its desolation.

The level design itself is bursting with a creative energy that threatens to belie the despondency of the atmosphere. Padgett has crafted a series of devilishly clever levels that, at their height, evoke such games as Portal, Rochard, and VVVVVV. They are at once staggeringly complex and intuitive to navigate. Padgett clearly could accomplish more in the early levels; certain elements are being held back.

But Padgett restrains his mechanical ambition to powerful effect. In the back half of the game, new mechanics are thrown at you with reckless abandon: lasers, jump pads, crumbling platforms, platforms that switch colors at random, astral projection à la Prey, teleportation à la Portal and gravity switching à la VVVVVV. Padgett eschews the typical pacing of a puzzle platformer— introduce new mechanic, allow you to acclimate to new mechanic, repeat—forcing you instead to cope with the overwhelming confusion of learning multiple mechanics simultaneously. This is survival horror in the language of a platformer. It’s staggering, sometimes stultifying, but always unique.

But does the game do its subject matter justice? As with Merritt Kopas’ Lim, Irritum’s sparseness works in its favor, allowing the player to map their own painful experiences onto its simple skeletal structure. The messages from Cassus and Sollus are vague but evocative, meaningful but interpretively porous. For Padgett, this is a game about memory and depression. In my own experience as a transgender woman, Irritum is a game about my relationship to my life prior to my gender transition.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-