Fela Kuti: Knitting Factory Reissues

Once controversial Nigerian artist’s body of work reissued and reconsidered

Koola Lobitos 1964-1968/ [9.8/10]

The ’69 Los Angeles Sessions [7.3/10]

Live! (with Ginger Baker) [6.2/10]

Shakara/London Scene [8.1/10]

Roforofo Fight/The Fela Singles [8.3/10]

Open & Close/Afrodisiac [8.5/10]

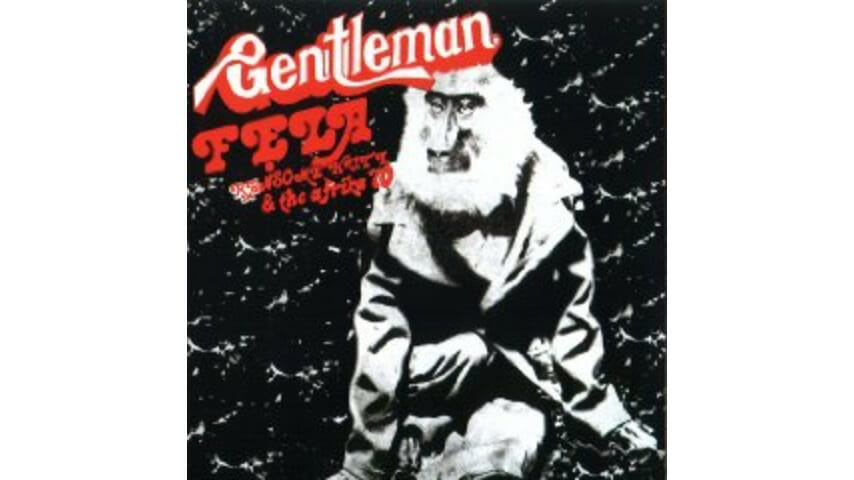

Confusion/Gentleman [9.3/10]

The idea that Fela Kuti—the outspoken Nigerian bandleader, polygamist, commune head, and thorn in the side of a military government that subjected him to constant harassment and several arrests—would someday become respectable enough for Broadway would have likely made Kuti himself laugh until smoke from his ubiquitous weed stash poured from his ears. Yet that’s exactly what has happened: Fela! opened at the Eugene O’Neill Theater to ecstatic reviews in November, and British director Steve McQueen (Hunger) is working on a film adaptation, with Jay-Z rumored to be involved. (Maybe he liked hip-hop DJ Mike Love’s 2008 mixtape Nigerian Gangster, which blends Jay’s vocals with Fela’s music.)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-