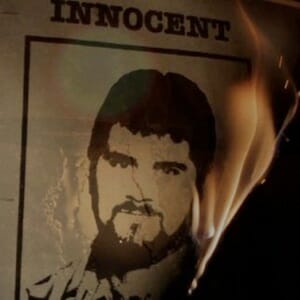

Incendiary: The Willingham Case

Granted, everyone loves an unlikely hero. But Cameron Todd Willingham was an unemployed man who beat his wife and was executed in 2004, after 12 years on death row for killing his three young daughters in a fire he set to their home.

But did he?

Incendiary: The Willingham Case is a smart documentary that opens with the following statement from one of many scholars interested in the case: “Committing arson at 9 a.m. is pretty uncommon.” A perfect opening, as it offers a single, common-sense explanation for the unlikelihood of Willingham’s alleged crime, even as the film goes on to debunk and dethrone the “common-sense” methods that got a man convicted of and put to death for a crime that most likely never occurred.

Directors Steve Mims and Joe Bailey Jr. tell the story skillfully. We hear from the scientists who prove—almost with ease—that the arson investigation was based on “fabrication, folklore, and witchcraft.” These moments in the film can be a bit tedious—few will find an extremely knowledgeable scientist explaining very thoroughly and in great detail the difference between arson and accidental fire riveting material. Nonetheless, it’s this deliberate unfolding of information that gives the case for Willingham’s exoneration its heft. Juxtaposed against the scientists is Willingham’s alleged trial lawyer, who speaks against his client with a down-home, Southern sensibility (complete with cricket noises and rooster crowing in the background). In one interview, he draws parallels between O.J. Simpson and Cameron Todd Willingham: “If he’d-a been black, and Vasquez [the lead fire investigator] had-a said ‘nigger’ at some point in his life, we could-a used that.” The moment is so real and so honest, it’s hilarious: Willingham’s own defense attorney, implying that his client got what O.J. deserved.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-