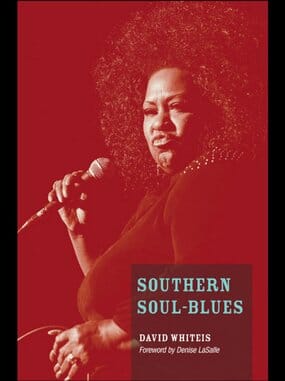

Southern Soul-Blues (Music In American Life) by David Whiteis

Loving Too Long To Stop Now

Books Reviews

David Whiteis proposes in Southern Soul-Blues to offer “a snapshot of the current southern soul-blues scene and…an argument for the music as representing a living tradition rooted in the same lineage as earlier soul, R&B, and blues.”

The first half of this seems a worthy goal—little of this music gets on the radio these days, and a lot doesn’t make it out of the South. Many non-Southern listeners won’t be acquainted with Sweet Angel or Ms. Jody or a number of other artists discussed.

Whiteis’ second intention, however, strikes this reviewer as unnecessary. Who would argue that the deep soul being made now doesn’t share lineage with the soul, R&B and blues before it? Loss of national commercial significance does not wipe out ancestry. Whiteis’ mission statement reflects the basic struggle of his book.

Deep soul, or Southern soul, peaked in the mid- to late-’60s and early ‘70s. While Northern soul studios often looked to cross over to white audiences with smoothness and swing, their Southern counterparts, at Stax, Fame and Muscle Shoals, maintained a more explicit link to the blues—fiery guitar licks, thwacking percussion, battering-ram horn sections. Singers like Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin and Etta James emoted explosively in these Southern studios. Their mountainous voices threatened to consume not only their selves, but their surroundings.

These studios achieved success despite and because of their grit. The famous critic Bob Christgau wrote one of his early pieces about the way the “love crowd” went wild for Redding at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967. After a series of unsuccessful albums with the Columbia label, Franklin went to No. 2 on the pop charts with I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You, recorded at Muscle Shoals. The Rolling Stones had so much respect for Southern soul they stopped by the very same studio to record a couple of tracks for Sticky Fingers. And in 1974, Lynyrd Skynyrd wrote about the musicians of Muscle Shoals in still-ubiquitous “Sweet Home Alabama”: “Now Muscle Shoals has got the Swampers/ And they’ve been known to pick a song or two/…They pick me up when I’m feeling blue.”

Even so, the glory days of Southern soul were numbered. In the ‘70s, lusher, more complicated soul and funk became popular, with some Southern singers like Isaac Hayes (who wrote many of Stax’s ‘60s hits) and Al Green at the forefront of this transition. Green in particular created a stunning body of work in the ‘70s for Hi Records in Memphis—light, precise, orchestrated and sensual albums that still had the emotional impact that a singer like Pickett achieved with his hammer-and-anvil. By the end of the ‘70s, the seamless percolation of disco reigned supreme, and R&B actively incorporated new technology like synthesizers and drum machines. Deep soul occasionally hit the charts again, but it rarely crossed over, and it never proved the same engine of commercial success.

Many of its singers tried to adapt. Others resigned themselves to blues festivals and a local circuit that had been the norm before singers like Redding broke into the mainstream. A lot of labels died. Recently, the grittier sound has actually been making somewhat of a comeback outside the South, partly due to the rise of labels reissuing albums they believe should’ve gotten more attention the first time around—for example, ‘70s soul albums by Swamp Dogg and Irma Thomas. The labels also dig into old reels of tape for unknown soul songs. Finally, older artists like Lee Fields and Bobby Womack now work with hip labels to get their music more attention…and newer groups like the Alabama Shakes have been well-received and nominated for Grammy awards.

In Southern Soul-Blues, Whiteis wants to make a case for the genre as still vital, worthy of more attention, yet he often ends up taking sides in debates that readers may not believe even exist.

“It’s apparent,” writes Whiteis, “that soul was less a rejection of the earlier blues aesthetic than a savvy updating of it.” Hard to imagine an objection to this stance, right? At another point, he discusses a split within the Southern soul-blues community over the sexual content of the music (this chapter of the book may be one of the best-named book chapters in recent memory—“The Raunch Debate: Hoochification Or Sexual Healing?”). Whiteis suggests that explicit sexual references have been “blamed for everything from defiling the music’s legacy to driving away respectable…listeners,” and he makes the case that sex has been in the music since the beginning. Again, the carnal edge of early blues recordings has been laboriously documented.

Occasionally, Whiteis commits a worse sin than stating the obvious. He stretches the truth.

“By any objective standards,” he writes, “the stylistic difference between an R&B superstar like Jay-Z or Usher and a southern soul artist such as Sir Charles Jones…may be more a matter of marketing than music…the stories told, the overall vocal and musical approach, and the production values have become so similar as to make critical distinctions different.”

Okay…Jay-Z, Usher and Sir Charles Jones all use relatively modern technology, and these three artists—along with much of the musical world—often touch on similar subjects in their songs (to interpolate a Jay-Z hit: money, cash and ladies, or lack thereof). But does Whiteis seriously suggest that the only difference between Jay-Z and Sir Charles Jones is marketing?

Southern Soul-Blues builds its argument by examining the careers of some relatively unknown older artists and some relatively unknown newer artists (though one charted in 1984). The old gang includes Latimore—who hit big in 1974 with the sexual funk of “Let’s Straighten It Out”—and Denise Lasalle, who went to the top spot in the R&B charts in 1971 with “Trapped By A Thing Called Love,” this recorded at Hi Records, the home of top-notch singers, including Green and Ann Peebles. Whiteis does a nice thing here, giving voice to artists unlikely to be a subject of books. But a reader who prefers Peebles’ early ‘70s albums to Lasalle’s…or who isn’t compelled by Latimore’s work aside from “Let’s Straighten It Out”…may not glean much from this section, aside from confirmation that the life of most professional musicians is a long, brutal slog.

The discussion of newer singers leads to the book’s most important question, namely, why isn’t deep soul commercially viable in the same way it once was? One possible explanation: “‘They’re assholes,’ Blackfoot [who sang with the Soul Children on Stax in the late ‘60s and enjoys a solo career as well] barks,” in an interview. He blames “radio DJs and station managers who he feels unjustly ignore his music.”

It’s hard to speak to the truth of this assertion. Even if it is all the radio’s fault, it begs the follow-up question: why did they stop playing the music?

Whiteis suggests another possibility—the music fails to be “popular among a small coterie of counter-culturally correct bohemians.” This also may or may not be true. The New Yorker loves Bettye Lavette; Lee Fields records for a Brooklyn record label; Betty Wright recorded with the Roots; Bobby Womack recorded with the producer Richard Russell, who has worked with successful indie groups. This sounds like the right group of people.

But either way, deep soul used to be popular with the “counter-culturally correct bohemians”—Christgau’s “love crowd”—so we face the same question: What changed? Whiteis doesn’t offer much in the way of explanation. Finally, a genre of music that seems crucial to this conversation—namely, rap—hardly makes an appearance in the book.

There may yet be hope. A 40-year industry veteran interviewed in the book believes, “southern soul…is something that could really make a lot of money for record companies.” The author notes that, “Survival through hard times has been the essence of its message since the beginning,” so maybe Southern soul-blues can weather the storm and come out the other side. After all, Robin Thicke has been all over the top of the charts with a re-working of Marvin Gaye’s 1977 hit “Got To Give It Up.” What’s to prevent someone playing around with old deep-soul ballads and crossing over with them?

If this music hopes to return to commercial prominence as an art form, its artists need to understand why it went out of favor in the first place.

Elias Leight is getting a Ph.D. at Princeton in politics. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and writes about music at signothetimesblog.