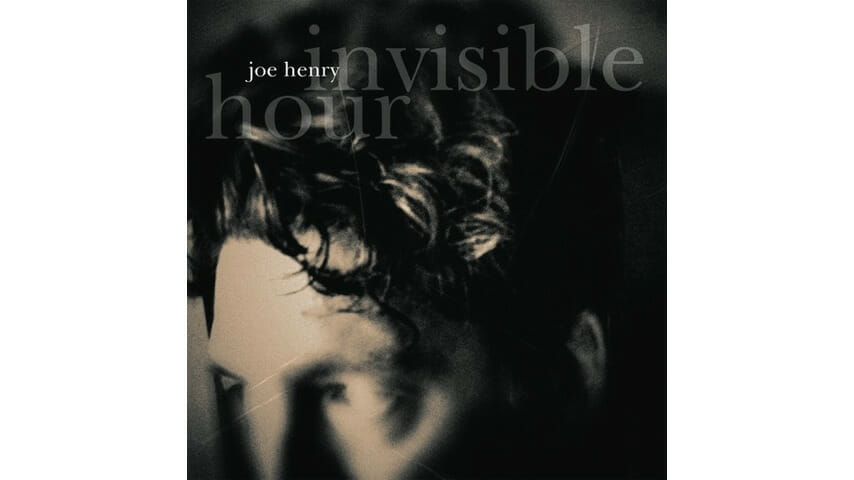

Joe Henry: Invisible Hour

Joe Henry doesn’t write love songs, although love suffuses almost every syllable he sings. He writes marriage songs, which are neither dewy-eyed odes to blossoming romance nor tell-all dispatches of domestic warfare, but rather something far more sly and wise and sweet. Forget the silly arguments about squeezing the tube of toothpaste from the top or bottom. Henry knows that the real work of marriage, and the real joy, involves the collision of two independent, willful, frequently selfish human beings, thrown together and destined to sort it out over the course of years and decades. What happens there—that strange and seductive alchemy that transforms and ennobles human lives, at least in the best of circumstances—cannot be summarized objectively, and perhaps can best be approached through the realm of gritty poetry, in words that bear witness to the scars, but still soar. That’s what Joe Henry has delivered on Invisible Hour, his 13th album.

And make no mistake, Joe Henry is a poet. He plays guitar (and guitar only; no piano on this album) and sings, and does his song-and-dance man shuffle, but more than any other contemporary songwriter, his words are luminous and mysterious, shimmering with the possibility of transcendence. Unlike Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks or Jackson Browne’s Late for the Sky, poetic confessional singer/songwriter albums with which Invisible Hour can be legitimately compared in terms of overriding lyrical themes and extraordinary musical quality, this one doesn’t end in despair and heartbreak. But the emotional stakes are just as high, the psychic wounds are just as great, and the 11 songs here are just as vulnerable and raw. “Our very blood tastes like honey,” Henry sings on the opening track “Sparrow,” and that arresting image, both alarming and life-affirming, sets the tone for the tales that follow.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-