Stealth games can feel pretty artificial. Though the genre is meant to simulate the sort of behavior a real person might exhibit—investigating a strange noise off in the distance, ignoring a barely noticeable shape in a room’s periphery—turning these actions into game mechanics requires rigid systems. Stick too close to reality and a player will be hunted across entire levels by guards who refuse to shrug their shoulders and return to their posts after spotting an intruder. Model natural bodily ticks, like glancing over a shoulder, and the action becomes too unpredictable. To make videogame stealth enjoyable, it’s necessary to codify human behavior—to render the erratic with a computer’s logic.

Bithell Games’ Volume is about this struggle. Its attempt to merge the organic and artificial shapes not only the game’s aesthetic, but its storyline and mechanical design, too. This isn’t a new concern for Bithell. His previous game, Thomas Was Alone, developed a cast of emotionally-driven characters out of puzzle-solving artificial intelligences drawn as utilitarian geometric shapes. Volume goes a step further, setting itself in a dystopic England where technology and unchecked corporatism have exerted a stranglehold on humanity. In its world, people have been subjugated, pressed under the thumb of a totalitarian government’s technocratic order.

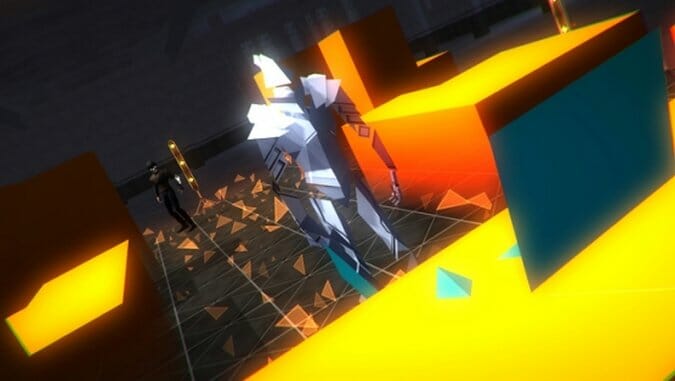

Protagonist Robert Locksley puts the plot in motion by subverting this, breaking into a military training center—dubbed a Volume—capable of turning a warehouse into a virtual representation of nearly any environment. After hijacking the Volume’s AI, Locksley begins running through digitized versions of the homes and offices of England’s corporate elite. By broadcasting himself sneaking around, outwitting guards, and grabbing floating gems meant to represent the upper classes’ money and secrets, Locksley hopes to inspire viewers to follow suit in the real world. He wants to provoke a people’s revolution by reversing his government’s means of control.

The story is meant to play as a kind of cyberpunk update of the Robin Hood legend, reworked for an era where the oppression of an aristocratic Sherriff of Nottingham is more suitably represented by a law manipulating business like Volume’s Gisborne Industries. What’s most striking about the game, though, isn’t its well presented yet fairly familiar take on corporate greed, but its decision to represent the underdog potentialities of the internet as the Sherwood Forest its heroes strike from.

As Locksley gains a fan following by successfully stealing from simulacrums of Gisborne associates’ homes—conveyed as a neatly segmented series of 100 levels—his popularity escalates in proportion to the danger he places himself in. Viewers from across poverty-ridden future England tune in to watch as Locksley shows just how possible it is for people like him to overthrow the system they seem bound to.

In game terms, this is all conveyed through bits of voiced dialogue and snippets of text found during play. In each of Volume’s sparse, fluorescently lit levels, the player guides Locksley past guards—whose field of vision is represented, early Metal Gear Solid style, by colored “awareness” cones. He grabs gadgets, slips past enemies, and collects the gems required to activate an exit. Though the game and its plot appear pretty rote over the first dozen or so levels, Volume increases in complexity as it continues. New items are introduced gradually, Locksley discovering tools like a limited-use invisibility field, enemy-stunning blackjack, and distracting noise-makers.

Each of the levels is an exactingly designed movement puzzle, the right angles of their corridors crafted to encourage specific solutions. Since being spotted is almost impossible to recover from—Locksley can try to slip the alerted guards by crouching around a corner, constantly relocating as they search—failure is a constant. Volume tries to compensate for this by generously distributing checkpoints throughout the levels, but Locksley’s vulnerability can still make for frustrating moments of repeated trial and error. Luckily, the game is more interested in increasing its level variety than difficulty. New gadgets force the player into new ways of thinking rather than simply testing their reflexes. (That said, it’s only a matter of time until some enterprising Frankensteins use the included level creation tools to craft nearly unbeatable monsters.)

Because the challenge stays reasonable enough throughout, Volume’s stealth systems remain satisfying and, most importantly, a consistent echo of the game’s narrative. The player, as human as the downtrodden English hoping to free themselves from Gisborne, is constantly overcoming the artificiality of the virtual environments, clockwork guards, and, of course, the cold logic of the stealth genre itself. As the plot unfolds, smartly considered parallels begin to emerge between the player’s input and the actions of the game’s heroes. By the time the story has finished, Bithell Games’ preoccupation with finding the humanity in our technology makes an awful lot of sense. In videogames—and in the computers we use to play them—we can find a lot more warmth than we see at first glance. It takes a thoughtful developer to make this argument and a pretty clever one to use a stealth game to deliver the message.

Volume was developed and published by Bithell Games. Our review is based on the PC version. It is also available for the PlayStation 4, PS Vita, and Mac.

Reid McCarter is a writer and editor based in Toronto. His work has appeared at Kill Screen, VICE, Playboy, and The Escapist. He is also co-editor of SHOOTER (a compilation of critical essays on the shooter genre), runs Digital Love Child, and tweets @reidmccarter.