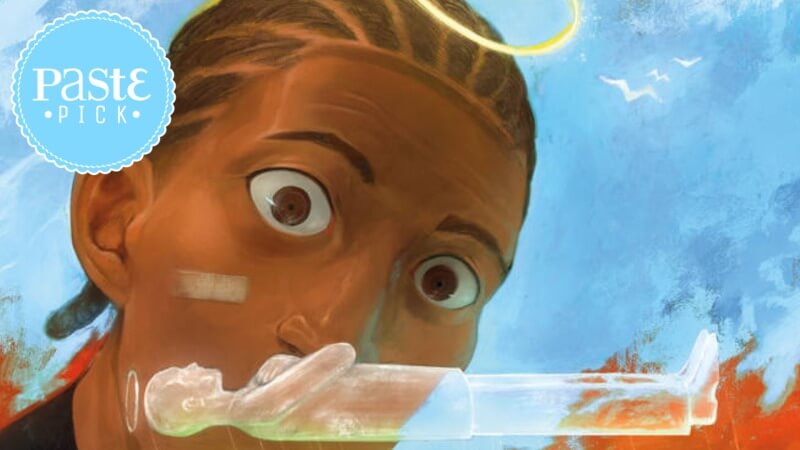

McKinley Dixon Finds His Wings in the Bombast of Magic, Alive!

Paste Pick: The Chicago rapper’s fifth album is a conceptual achievement—not just a story of three young kids whose friend passes away, the monuments they build in his memory, and the lives they’d kill themselves to restore, but a collection of 11 short stories touched by a block-wide echo.

McKinley Dixon is on one hell of a run. Ever since dropping Who Taught You to Hate Yourself? and The Importance of Self Belief back-to-back in 2018, the Virginia-raised, Chicago-based rapper has periodically released the best rap novel of all-time—only to one-up himself again two or three years later on the next. He’s been skyrocketing for nearly half-a-generation, chronicling the poetry of the world like he’s got Frank O’Hara’s eye and June Jordan’s vocab. His processing is a mode of time travel, his songs are disinterested in forgoing brutality for the sake of safety. Songs like “Run, Run, Run” and “Tyler Forever” are sun-dappled, street-corner proverbs—depictions of violence, Blackness, and friendship staged in the literary. And Dixon’s sonic come-up is a feat of its own: The horns that underlined “Circle the Block” seven years ago keep getting more muscular; his flow, once lo-fi and monotone on a track like “The Everyday People,” is louder and closer to the mic. What makes Dixon such a rap bona fide in 2025 is how his tongue is a museum. Listening to his music, you can learn a thing or two about love and consequence, about the line of survival blurred in-between. He tends to Black art by approaching his albums like memoirs.

In 2021, his breakthrough LP For My Mama and Anyone Who Look Like Her denounced martyrdom by bringing everyone in on the riches, be it Teller Bank$, Alfred., Michah James, or Abby T. Dixon wrote for and to the women in his life, about the mortality of his elders in the context of him and his friends just trying to get by (“Chain Sooo Heavy”). His kinfolk are the tastemakers (“make a poet Black”), and the big door prize is feeling alive (“Bless the Child”). Four years ago, Dixon looked at how white art culled from trauma is praised and began unpacking why Black creators who search for accolades from God-playing think-tanks are asked to be sadomasochistic while conversing with their own turmoils. He turned the camera even further inward on 2023’s Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?—an album inspired by the Roots and Dream Warriors, hellbent on outrunning the system, and generous for how much tenderness it finds in the dimmest pockets of living.

Magic, Alive! is McKinley Dixon’s fifth album, and it’s also the biggest risk he’s taken yet—a collection of tracks always flirting with overproduction and clutter. The music is brimming with orchestration; it’s not “everything but the kitchen sink,” but “everything and the kitchen table.” Dixon isn’t afraid to add more voices and hands into his musical soup, and each song is an elixir of jazz-rap, with pockets layered in chain-link grandeur. Every chapter of Magic, Alive! is bigger than him, yet his verses focus on the micro with historical hip-hop citations, literary allusions, and horror films metabolized into heady sonic palettes. Like the illustrations he animates in his spare time, the rarely-pedantic Dixon meticulously sketches expressions of people he both knows and imagines. His lyrical fascinations with mythology are decorated in rare and endangered fits of orchestral patterns; the noisy percussion, mechanical poetry, and blood-boiling strings haunt the magic Dixon is chasing in the epilogue of Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?’s block-bending cynicism but never smear it. As he raps on “Listen Gentle”: “It’s tragic, trying to keep my kindness in my steps with lightning in my eyes.”

Magic, Alive! is a conceptual, allegorical achievement—a story of three young kids whose friend passes away, the monuments they build in his memory, and the lives they’d kill themselves to restore. To preserve the light of a loved one, Dixon assembled a guest list featuring both veterans of his catalogue and green players who’ve been running in nearby circles, including Quelle Chris, Anjimile, Ghais Guevera, Alfred., Teller Bank$, ICECOLDBISHOP, Pink Siifu, Blu, and Shamir. “Watch My Hands” begins in a familiar neighborhood scene: little homies wearing beaters in a hot summer, watching the world “from the back of a bike.” Dixon raps so nonchalantly you can hear him laugh at the head of the first verse and, while the resonance of Eli Owens’ harp glistens, he puffs out his chest: “Be as strong as the concrete, but as fragile as when it and ya knees kiss.” Softness clots in “A Crooked Stick” and its aftermath, when Dixon declares himself “alive through close calls” and meets his own survival and curse defiance with an “I guess.” In the miscellany of jousting saxophones and walloping drums before and after Dixon, Alfred. raps about TikTok dances, Rick Ross ad-libs, and “NPC white noise, blip-blop.”

McKinley Dixon sinks his teeth into the Magic, Alive! story on “We’re Outside, Rejoice!,” as he summons a concrete pastoral again but doesn’t wear out its meaning. There are far too many front doors still unopened on his turf to stop painting the neighborhood just yet. A tint of blue washes over the brotherhood at the song’s core: “I love laying with you here in the grass, feels like it was just us in the worlds that passed.” Dixon speaks in Toni Morrison titles while seeking redemption and clinging to memories the bodies around him have sung into life. “My face inhales the sun, grab your hand with no plan then we run!”