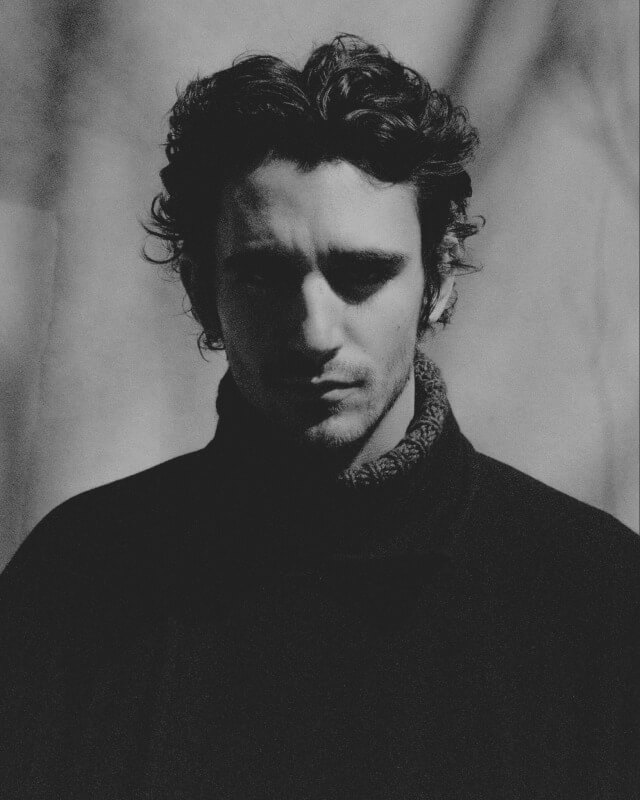

Tamino Embraces the Dawn

The Belgian-Egyptian musician sat down with Paste to discuss writing with urgency, creating intimacy through visuals, and his new album, Every Dawn’s a Mountain.

Photo by Ramy Moharam Fouad

Tamino-Amir Moharam Fouad—known mononymously as Tamino—performs to sold-out crowds around the world, reaps the praises of artists like Lana Del Rey and Radiohead bassist Colin Greenwood, and graces billboards as the face of a new Hermès fragrance campaign. But in his rearview mirror, there’s a scrawny 14-year-old hunkered down at his piano, writing his first-ever song about a girl. Like countless other hymns of lovesick teenagers, it (to paraphrase the man himself) kind of sucked. That was no matter, though. From his first brush with songcraft, the Belgian-Egyptian musician was hooked.

In 2017, barely out of his teens, Tamino released his first single, “Habibi,” a song that, in hindsight, was a thorough preview of what would become the hallmarks of his distinctive artistry: sonic stylings reflecting his Egyptian and Lebanese ancestry, lyrics that channel indescribably intense feeling into tangible imagery, and a voice both virtuosic and visceral. I’ll never forget hearing it for the first time in my senior year—the moody minor chords, feverish poetry, and skyscraping falsetto transporting me from the dry, fluorescent heat of my high school library. After the song ended, I hastily sent myself a text, in part to ensure I wouldn’t forget about the artist who’d granted momentary refuge from the pits of pre-class dread, but also to vent the ever-exhilarating thrill of discovery: “TAMINO!”

Nearly three years later, when I meet “Mino”—as he’s identified in the lower-left corner of my laptop screen—over a video-call in June, he’s between legs of an extensive North American and European tour in support of his haunting third album, Every Dawn’s a Mountain (released in March via erēmia/Communion Records). Even on my slightly blurry screen, the 28-year-old exudes the same poise and style as in photoshoots and in concert, sporting a mint-green collared shirt, a delicate silver chain, and a silver bracelet revealed by the occasional hand gesture—but even so, he isn’t the intimidating presence one might expect. The warm smile he greets me with immediately dispels my nerves, and he wears it often throughout our conversation. Despite being a self-professed introvert, he absolutely lights up when talking about music, graciously receiving and expanding upon my own interpretations of his work. Before I know it, our interview creeps past the hour I’d scheduled.

Tamino calls from his former home in Antwerp, Belgium, where he wrote the earliest fragments that would become Every Dawn’s a Mountain over two years later. Considering his characterization of the album as “a metaphysical altar for what had been lost” in its accompanying biography, I ask if he’s willing to expand upon what, exactly, had been lost that compelled him to compose such a work back when he lived in this same home. He admits that, throughout the press cycle, he’s been hesitant to divulge specifics about that pivotal period, fearing that doing so would water down the record into a “one-dimensional” work for listeners, particularly because the experience of loss is anything but. “I think it really contains multitudes,” he muses, “and even the form of grief, and of letting go—it has taken many forms.” He pauses, before reflecting on how he’s felt the songs “transform” as he’s performed them. It seems only natural that they’d acquire deeper meanings with time—especially as listeners have refracted the aches and awe they hold right back to him by singing along. As a result of sitting with the work alongside his audience, Tamino’s initial guardedness has begun to dissipate: “I do feel a little bit more confident now to give more context,” he says, “and I also realize that a little bit of context is welcome for people.” Anxious not to seem prying, I insist that he shares only what he feels comfortable with. But he briskly waves away my concern: “No, no, no! I really see the importance of it now, and I appreciate the opportunity.”

In the fall of 2023, Tamino relocated across the Atlantic, from Antwerp to New York City. It was far from a hasty decision; since 2022, he had taken numerous month-long visits to the city to confirm he wasn’t making a monumental mistake. In retrospect, he can say the move was inevitable: “It was an ‘I’m already hooked’ kind of thing,” he says. Thanks, in part, to his earlier test runs, it didn’t take him long to adjust to life in Manhattan; he even tells me it feels like he’s lived there far longer than he has. But that is not to say, of course, that uprooting his life and moving 3,000 miles from home was easy. “I had left it behind before, when I moved to Amsterdam when I was 17 [to study music at the Royal Conservatory], but it’s so close to home that it’s different,” he explains.

The move was only one of several major life changes that threw Tamino into what he calls a “state of complete disorder.” Soon before leaving Antwerp, he and his girlfriend of seven years separated. Around the same time, one of his close friends died. “I met him around the same time my relationship with my ex started,” Tamino says. “It was suddenly like these two very big chapters in my life came to an end, and they started at the same time, as well. We’re talking a period of seven years, which, according to many people, that’s like a cycle in your life, where all your brain cells are fully changed, or replaced.” Tamino is a self-professed lover of such “synchronicities”—a more pleasant one he mentions later is that New York used to be called New Amsterdam—although, he clarifies, he’s hesitant to “symbolically draw” connections between these coincidences. “But, I mean, we’re talking about the album,” he concedes, “so, yeah, [that’s] inevitable.” Tamino may not be a critic, but he’s well-versed in teasing out those symbolic connections in his own work, readily examining his art from multiple angles.

This level of care, however, can be a double-edged sword, often resulting in self-consciousness and perfectionism—and endearingly, Tamino is no exception to that rule. About 20 minutes into our conversation, he smiles sheepishly, “I try to avoid my own music as much as possible.” As a fan, I admittedly can’t resist blurting out, “Really?” He shrugs it off. “Yeah, I can get deeply insecure when it comes to finished work. I stand behind it—I stand behind it 100 percent. But it’s hard to…” He pauses, considering. “It depends on my mood, let’s put it like that.”

If Tamino is his own biggest critic, that’s only symptomatic of the thoughtfulness with which he creates and understands his art. As much as he might feel an aversion to his own music, he discusses it freely, with the fervor and artistry of a poet—and, frankly, the thoroughness of a music critic. He’s patient and precise in choosing his words, often translating his thoughts into vivid metaphors (he analogizes the construction of songs to a child’s eager assembly of a Lego set, and compares the refinement stage to the process of painting a full-scale house) and tracing elegant throughlines across the chapters of his life and discography. After I note how the title of his new album relates to that of his last, Sahar—an Arabic word that roughly translates to “just before dawn”—he draws an even closer connection between the records. “Even the last line of the second album is ‘Before I step into darker days,” he points out, alluding to Sahar’s devastating closer, “My Dearest Friend and Enemy.” “I mean, that song was already hinting at a separation and at a struggle that would follow. Looking back on that last song of that album, that last line, the title of the record, I think [the title of the third] is all the more fitting.”

However, Tamino didn’t start writing with the album title already in mind. Instead, the record’s title track—where the phrase is taken from—spilled out of Tamino almost as soon as he realized it was there. “When I started writing, it was like giving birth—like, ‘It’s coming, now!’ Like, ‘I have to give birth to this song right now; otherwise, it’s gonna die,’” he laughs. When he finished the song, the lyric “every dawn’s a mountain” stood out as a natural choice for the song’s title. “At some point in the weeks after, I started contemplating it as a potential title for the album,” he says. “And I did think, like, ‘Oh, yeah, my previous record also was related to dawn,’ and I started seeing a symbolic beauty to that: ‘just before dawn,’ and ‘Every Dawn’s a Mountain.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-