The 100 Best Martial Arts Movies of All Time

Fighting, whether sanctioned or no-holds-barred, is without a doubt the oldest form of competition that mankind has ever engaged in. At times, it has been a necessary tool of survival—kill or be killed—and that proved an extremely effective motivation and crucible for enhancing mankind’s fighting prowess. Technology rapidly came into play and has been seen out to its inevitable conclusion, which removes man from the equation almost entirely. Today, robotic drones are poised to do much of our fighting for us—whether we ultimately end up in a Robot Jox scenario where wars are decided by giant mech battles is a valid (and awesome) question.

And yet, despite all of our sophistication and technology, we still fight by hand as well. Some is driven by necessity. Others fight professionally, and have only continued to expand the complete picture of what a fighter is. Look at the exponential growth in sophistication from the early days of mixed martial arts to how the sport has become in 2015, going from big guys winging punches at one another to a beautiful, scientific system of mixed grappling and striking styles. The audience has never been bigger, because on some level, we love fighting, if only because it reminds us of our most primal roots that have long been shelved and put aside by civilization.

And nowhere is appreciation for the beauty of fighting more apparent than in the wide, storied genre of martial arts cinema. Violence is the selling point of these films, but seeing as that violence is achieved through trickery, stunt work and movie magic, it’s not truly the audience’s bloodlust that drives the industry. It’s an appreciation for the beauty of violence, a reminder of the exceptional abilities derived through training and a celebration of ancient, classical storytelling, in the vein of “Avenge me!” No genre reveres classic themes as this one does, because at their root they speak to us like cinematic comfort food, and they provide excuses for what people have really wanted to see all along: The action.

And so, let us celebrate the martial arts genre from its top to its bottom, old and new. Epic and modest. Comedic and tragic. Grave and absurd, all represented in equal measure. These films contain many wondrous sights: Monks training their bodies to repel bullets. Men with prosthetic iron hands shooting poison darts. Flying heads. Incredibly silly ninja costumes. It’s all here.

But please note: Don’t look for Seven Samurai, Yojimbo or The Sword of Doom here. Although they’re all great films, we wanted this list to focus squarely on our conception of “martial arts cinema,” which has little in common with a great samurai drama by Akira Kurosawa. These films are action-packed fighting spectacles, but above all, they’re just plain fun.

Here are the 100 best martial arts movies of all time:

100. Ninja TerminatorYear: 1985

Director: Godfrey Ho

This is a list of the 100 greatest martial arts films of all time, but at the tail end, let us make a small space for those flicks that are enjoyable but unquestionably of extremely low quality. And oh my, Ninja Terminator is certainly that. Perhaps the single most infamous film in the legendarily cheap career of Hong Kong z-film auteur Godfrey Ho, it displays most of his trademarks—primarily footage from multiple, unrelated movies spliced together to create a sort of “movie loaf” of unrelated fight scenes and nonsensical dubbing. Half of the movie revolves around American actor Richard Harrison seeking a cheap plastic statue that grants super ninja powers, while an unrelated plot features one of screendom’s great badass heroes, “Jaguar Wong,” vs. some guy in a bizarre blonde wig. At this point, you may be thinking “It will make more sense when I’m actually watching,” but you would be fatally wrong. All in all, though, Ninja Terminator is hilariously mangled viewing. —Jim Vorel

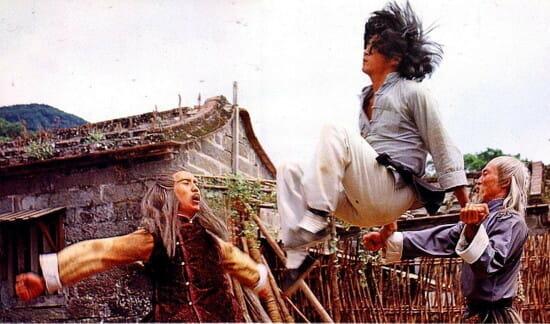

99. Battle WizardYear: 1977

Director: Hsueh Li Pao

By the end of the ’70s, Hong Kong kung fu cinema had reached the apex of its classical period and began to fork paths wildly, hurtling down a road of ever-increasing decadence and, finally, absurdity. One of the main offshoots were films in the vein of Battle Wizard, which combined a hodgepodge of Eastern and Western mysticism and magic into stories that otherwise resemble classic period piece kung fu films. The result is like throwing several movies in a blender and just hitting “puree”—flying wizards hurling lightning bolts, ghosts, monsters vs. the flying fists of proud kung fu warriors. The only way to truly understand is to just witness a few minutes of a film like Battle Wizard. Is that a kung fu-fighting guy in a gorilla suit? Yep. A fire-breathing wizard with extendable wooden chicken legs? Sure. A man swallowing a glowing frog whole? Of course. This is Battle Wizard, fool. —Jim Vorel

98. Ninja III: The DominationYear: 1984

Director: Sam Firstenberg

You will quickly suss out that a lot of the “fun-bad” movies at the bottom of the list are ninja-centric: This is not a coincidence. In the 1980s, ninjas came into the vogue as bad movie villains du jour in both American and cheap z-grade Chinese cinema, even though the depiction had pretty much nothing to do with historical ninjitsu. On the positive side, it gave us Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. On the negative, the likes of Ninja III: The Domination, but few of these films are as campily bad as this one. The story revolves around an aerobics instructor (all women in ’80s films are aerobics instructors) who is possessed by the spirit of an evil ninja who can only be defeated in one-on-one ninja combat. Soon, swords are levitating, exorcisms are happening, and a hapless executive just trying to have a nice round of golf finds himself hunted by bloodthirsty golf ninjas. —Jim Vorel

97. Legend of the 7 Golden VampiresYear: 1974

Director: Roy Ward Baker

Certainly one of the weirdest co-studio crossovers to come out of the ’70s, Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires is the product of veteran Hong Kong kung fu factory The Shaw Brothers teaming up with Hammer Studios, the makers of classic British ’50s and ’60s Frankenstein and Dracula films. In fact, this is actually the final Hammer “Dracula” in their long series, and the only one to (thank god) not star Christopher Lee as the count. Instead, the inane story is about Dracula traveling to rural China, where he takes control of a coven of seven Chinese vampires with desiccated, beef jerky faces. A 61-year-old Peter Cushing returns to the series as heroic Van Helsing to give one more go of it, but because his brittle bones weren’t capable of much more than standing at that point, he’s also backed up by a family of kung-fu brothers with cheap tin-foil weaponry. This led to the film’s hilarious American title: The Seven Brothers and Their One Sister Meet Dracula. Catchy! —Jim Vorel

96. Miami ConnectionYear: 1987

Director: Richard Park

Late ’80s? Check. Motorcycle-riding taekwondo synth rock bands? Check. Ninja drug smuggler gangs? That’s a big check. Miami Connection is one of the most deliriously entertaining and inexplicable films to ever disappear for a few decades before being rediscovered, as it blissfully was by The Alamo Drafthouse in the late 2000s. This alternatingly sincere and conceited vanity project was a labor of love from Y.K. Kim, a taekwondo proponent and motivational speaker who really seemed to believe that his film about positivity, music and severed limbs would help clean up the streets. It most assuredly failed at this, but on the plus side it gave us incredible, genuinely catchy songs like Friends Forever and the spectacle of Y.K. Kim pretending he knows how to play guitar. —Jim Vorel

95. Crippled MastersYear: 1979

Director: Joe Law

“Martial arts” is a sprawling, overarching film genre that encompasses several large offshoots and dozens of very niche micro-genres. How niche? Well, niche enough to support the term “cripsploitation” for movies like Crippled Masters. Unlike other films of the period that often portrayed otherwise able-bodied actors as handicapped fighters, however, Crippled Masters stars two genuinely handicapped people—a man with no arms and a man with no legs. They both play kung fu students who are crippled by their cruel master and train for years before seeking their revenge. I won’t lie to you—it’s a genuinely disturbing flick to watch at times, but there’s some legit physical talent on display. And to answer the obvious question: Yes, the guy with no legs eventually sits on the shoulders of the guy with no arms to form a Voltron-like super fighter. Obviously. —Jim Vorel

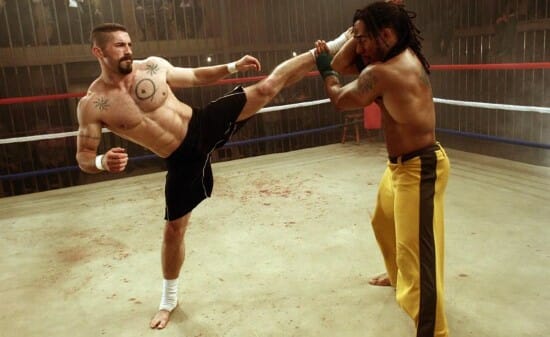

94. Undisputed 2Year: 2006

Director: Isaac Florentine

Ah, direct-to-video martial arts. Few genres are so direct in appeasing their fan-base: There’s no attempted subterfuge about who the audience is here. The men who watch these flicks aren’t watching for the story; they’re watching for the action, and action is the bar by which they’re all judged. In this, Undisputed 2 delivers thanks to its dual stars, Michael Jai White and Scott Adkins. The story is a half-serious attempt at sequelizing the 2002 Wesley Snipes/Ving Rhames prison boxing movie, but in reality this is simply name appropriation by a director who wanted to make a flashy martial arts flick. Michael Jai White plays a boxer fighting for his freedom, but once again: Doesn’t matter. You know what does matter? Spin-kicks. Spin-kicks and broken legs and slow-motion spin-kicks. —Jim Vorel

93. Undisputed 3Year: 2010

Director: Isaac Florentine

As it turns out, the breakout character of Undisputed 2 is actually the Russian villain Boyka, who here takes on the hero role. This sequel makes even less of an attempt to hide its desire to simply be a collection of individual fight scenes, and that actually makes for an even more entertaining exercise in film violence. It features that greatest of martial arts structuring devices: The tournament. Ever since Enter the Dragon, it’s been the premiere way of showcasing random fights without having to muck around with plot, and that’s what this film is all about. The tournament gives Boyka a variety of fighters with different styles to contend against, and we continue to be rewarded with the Undisputed series’ primary export: Absurdly impractical and undeniably beautiful spin-kicks. —Jim Vorel

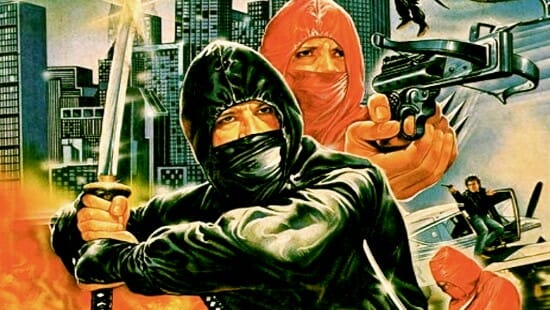

92. Enter the NinjaYear: 1981

Director: Menahem Golan

Have you ever seen someone dress as a ninja for Halloween? Or any ninja costume in general? If so, you pretty much have Enter the Ninja to thank. This is a genuinely terrible film, but a hugely influential and entertaining one as well. It is, in short, the film that firmly established most of the iconic ninja tropes in the West—the stereotypical black, masked outfits, the throwing stars, the katanas. Also notable as perhaps the first of the “This guy’s white, he can’t be a true ninja!” films, which would be copied incessantly for years. It’s also notable for introducing Sho Kosugi to an American audience, the guy who would go on to become the iconic ninja in nearly a dozen other films. Enter the Ninja might well be one of the most imitated films of the entire 1980s. —Jim Vorel

91. Zu: Warriors from the Magic MountainYear: 1983

Director: Tsui Hark

One thing no one can fault Tsui Hark for is his boundless ambition, which is why, next to Stephen Chow, Hark’s contributions to the canon of martial arts films are some of its biggest and most confusingly bloated. Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain may be the ballsiest of all of the Hong Kong director’s epic feats, an attempt to wed the action flicks of his home with the kind of big budget fantasy pieces beloved by Western audiences in the ’80s, and later made ubiquitous by directors like Jim Henson and Wolfgang Peterson. Although practically incomprehensible at times, Zu takes a standard mythological story—that of gods who inhabit a mountain fortress-like home and, in the process of defending that home from a benevolent enemy, take in a wayward but stubbornly idealistic mortal—and stuffs it with enough special effects to choke even the most dedicated workhorse of a fan. Gelatinous skull spirits and metal wing capes and weird asteroids where wiggly souls are reborn: best to let it just happen. That Tsui Hark also tapped into the core of what makes the goofiest martial arts films tick is something that, more than 30 years later, is still a testament to a director who made a film more veteran directors wouldn’t touch with a 10-foot, bamboo, 8-diagram-nurtured pole. —Dom Sinacola

90. American NinjaYear: 1985

Director: Sam Firstenberg

This is what happens when American audiences see Enter the Ninja and ask “Could the ninja be more American? And can we do away with the dubbing?” Still produced by Golan-Globus, it takes the ninja story and gives it a corny American twist—our hero is now Private Joe Armstrong, who “chooses to enlist in the U.S. Army rather than go to prison and finds himself fighting off ninjas on a base in the Philippines.” Ask any Filipino—those islands are rife with ninja. You can’t swing a nunchuck in the Philippines without hitting a ninja, I’m telling you. It was followed by four sequels and an unrelated movie called American Samurai from the same director because hey, why the hell not. You’re gonna want to showcase Michael Dudikoff as much as you can—“HE POSSESS GREAT SKILLS,” after all. —Jim Vorel

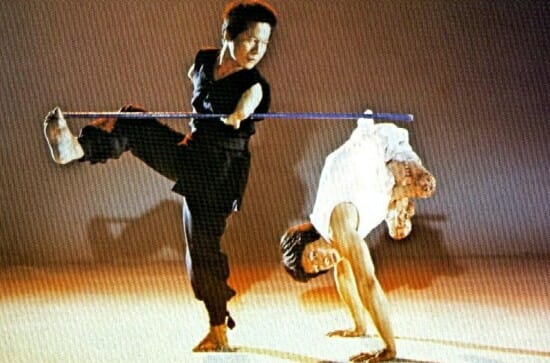

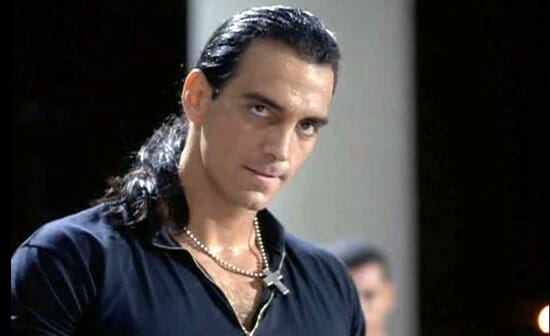

89. Only The StrongYear: 1993

Director: Sheldon Lettich

Many of the films so far have been profoundly ’80s, but Only the Strong is the early ’90s. It feels like the Full House of martial arts films, chock full of positivity, smiling, day-glo colors and life-lessons galore. Showcasing the dance-infused Brazilian martial art of capoeira, it stars future Iron Chef chairman Mark Dacascos as a soldier-turned-teacher who must clean up an exceedingly rowdy class of inner-city ne’er do wells by teaching them self-worth and occasionally by punching them in the face. It’s like an after-school special collided with a kung fu movie. The incredibly oily, metrosexual villain Silverio is particularly memorable—I love that the thing to send him into a rage in the final battle is having part of his luxurious, flowing hair cut off by a sword swipe. Thank god Mark’s students are there to sing a catchy tune and fill him with fighting spirit! —Jim Vorel

88. Mystery of Chessboxing, AKA Ninja CheckmateYear: 1979

Director: Joseph Kuo

Classic Hong Kong kung fu in style but somewhat unusual in its delivery, Mystery of Chessboxing is the sort of film that was churned out of China in the ’70s, many of which are now forgotten. A protagonist seeking revenge for his slain father is the stuff of kung fu cliché, but the flick does manage to stand out for a couple of reasons. First is the odd form of kung fu that the hero learns, which takes its cues from the movements of Xiangqi, also called Chinese chess. Second (and most importantly) is the film’s villain, the epically titled “Ghost-Faced Killer,” who hunts his targets before throwing down a decorative “ghost-faced killing plate” and dispatching them with his trademark Five Elements style. The name is of course the inspiration for Wu-Tang Clan member Ghostface Killah, who also appears on their kung fu song “Da Mystery of Chessboxin.” —Jim Vorel

87. Tai Chi ZeroYear: 2012

Director: Stephen Fung

A 3D spectacle down to its fat nuts and bolts, Tai Chi Zero recognizes no bounds, no lines, and no walls preventing it from being anything—and everything—it wants to be. A breathless mess of steampunk, underground comics, slapstick, farce, historical romance, and top hats, all duct-taped to a restless skeleton of fantasy cinema, Tai Chi Zero has its precisely placed thumbs in pretty much every proverbial pie. A proper heir to Stephen Chow’s broadly imagined kung fu world, Fung is a filmmaker who seems limitless in potential. Stay tuned: his Kickboxer reboot emerges later this year. There’s no doubt he’ll kill it. —Dom Sinacola

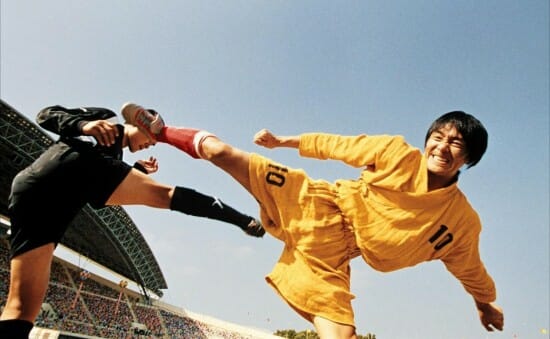

86. Shaolin SoccerYear: 2002

Director: Stephen Chow

Set in an alternate universe where the Three Stooges were down-on-their-luck monks and kung fu nothing more than a silly distraction from more lucrative adult matters, Shaolin Soccer somehow—between impromptu dance numbers, confusing body dynamics, self-help homilies, a whole lot of hilarious screaming, and an utter commitment to CGI—tells a warm-hearted tale about how martial arts is so much more than a way to kick your enemies in the face really hard. It’s a way of life. As such, Stephen Chow shines, suffusing every shot and every bit of visual minutiae with the unbridled excitement of both those who make action flicks and those who adoringly watch them. Though he’d later go on to perfect his madcap brand of big-budget, beat-em-up fantasy, Shaolin Soccer is nearly perfect as an example of a martial arts film that seems to exist on its own space-time continuum. —Dom Sinacola

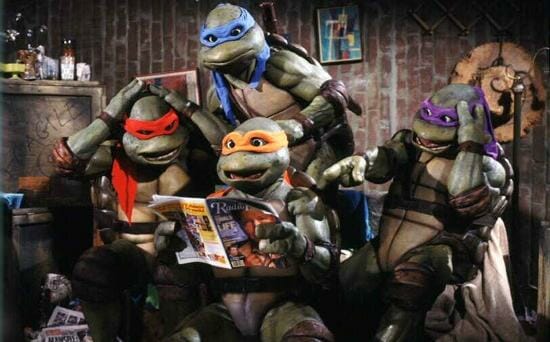

85. Teenage Mutant Ninja TurtlesYear: 1990

Director: Steve Barron

Akin more to a creeping chambara flick or a meditative piece of kung-fu canon than cash-grabbing kids’ fodder, the first live-action attempt at a Ninja Turtles movie now seems—after decades of reboots and big-budget spectacles geared at children but tailored to functionally no one (as any movie Michael Bay produces typically is)—a movie worthy of its workmanlike martial arts action. Once you get past the explicitly turtle-based finishing moves (like the shell-smushing knock-outs) and the Domino’s Pizza plugs, what’s left is a brooding narrative and surprisingly extended, unadorned fight scenes. Although Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is still staunchly a product of its time (featuring a young, greasy Sam Rockwell as “Head Thug,” no less), it’s also a handsome, even appealingly gritty film, shot with sepia filters and samurai silhouettes, and threaded throughout by the kinds of panoramic melees that all these years later M. Night Shyamalan attempted with The Last Airbender and then failed. Look especially to the brawl in April’s family’s antique shop to witness how four grown men in turtle costumes—that have gotta weigh a ton—combatting a bunch of ninjas can best serve director Barron’s unexpected talent at flushing out visual space in order to make a dead premise feel—seriously—lived in. Plus, this marks the only time you’ll ever find Corey Feldman on a list like this. —Dom Sinacola

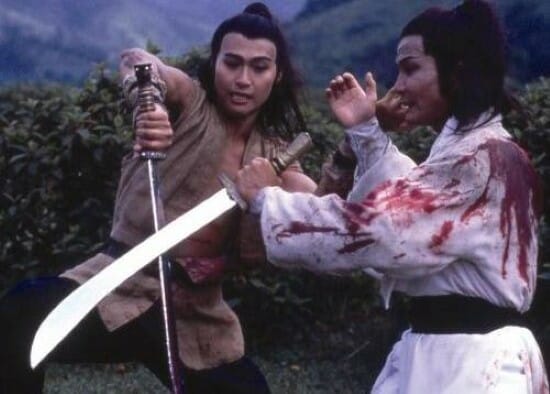

84. Sword Stained With Royal BloodYear: 1981

Director: Chang Cheh

This is the first film on the list both directed by prolific kung fu auteur Chang Cheh and starring the Venom Mob, but there will be several more. The Venom Mob were a group of Shaw Brothers martial artists who rose to fame in the late ’70s and became some of the biggest stars in their business for several years. Sword Stained With Royal Blood is one of their minor classics, but displays many of the classic trademarks, with beautifully choreographed action sequences, wonderful athleticism and a mix of different physical styles. The story is a bit of a sprawling coming-of-age tale about an exiled young boy who must train in kung fu and one day confront his father’s betrayers—classic kung fu stuff. Expect flying swords and acrobatics galore. —Jim Vorel

83. The Bride With White HairYear: 1993

Director: Ronny Yu

As much romance as martial arts, The Bride With White Hair is nonetheless filled with ultra-stylized, gory, head-scratching mayhem. In some sense, it has a Romeo and Juliet tinge of doomed lovers, if those lovers had the ability to fly and attack people with prehensile hair. The title character is a young woman who undergoes a terrible transformation when rejected by her lover, using her newfound powers to seek out those who have wronged her. The whole thing is shot in a very gauzy style with cold colors and odd, unnatural lighting that makes it feel like an especially vivid nightmare. It’s a film that waffles between silly melodrama and even sillier action at the drop of a hat, which is something one can often find in the wuxia martial arts subgenre where this at least partially resides. It’s difficult to define, but wuxia films typically feature this sort of mix of historical swashbuckling and romance over the training and fistfights of other martial arts movies. —Jim Vorel

82. The Paper TigersYear: 2021

Director: Bao Tran

When you’re a martial artist and your master dies under mysterious circumstances, you avenge their death. It’s what you do. It doesn’t matter if you’re a young man or if you’re firmly living that middle-aged life. Your teacher’s suspicious passing can’t go unanswered. So you grab your fellow disciples, put on your knee brace, pack a jar of IcyHot and a few Ibuprofen, and you put your nose to the ground looking for clues and for the culprit, even as your soft, sapped muscles cry out for a breather. That’s The Paper Tigers in short, a martial arts film from Bao Tran about the distance put between three men and their past glories by the rigors of their 40s. It’s about good old fashioned ass-whooping too, because a martial arts movie without ass-whoopings isn’t much of a movie at all. But Tran balances the meat of the genre (fight scenes) with potatoes (drama) plus a healthy dollop of spice (comedy), to similar effect as Stephen Chow in his own kung fu pastiches, a la Kung Fu Hustle and Shaolin Soccer, the latter being The Paper Tigers’ spiritual kin. Tran’s use of close-up cuts in his fight scenes helps give every punch and kick real impact. Amazing how showing the actor’s reactions to taking a fist to the face suddenly gives the action feeling and gravity, which in turn give the movie meaning to buttress its crowd-pleasing qualities. We need more movies like The Paper Tigers, movies that understand the joy of a well-orchestrated fight (and for that matter how to orchestrate a fight well), that celebrate the “art” in “martial arts” and that know how to make a bum knee into a killer running gag. The realness Tran weaves into his story is welcome, but the smart filmmaking is what makes The Paper Tigers a delight from start to finish. —Andy Crump

81. EquilibriumYear: 2002

Director: Kurt Wimmer

In Equilibrium, Taye Diggs plays a future fascist law enforcement officer named Brandt, and near the climax of the film, Brandt gets his face cut off. That’s his whole face, impeccably separated from his head, hair- to jaw-line. This follows a kind of lightning-quick, future samurai sword fight in which Christian Bale’s character, the heroically named John Preston, has singlehandedly massacred his way, gun in one hand and sword in the other, through one law enforcement officer after another, determined to wrench humanity from the binds of a totalitarian state that has outlawed—you guessed it—feelings. Much like Taye Diggs’ face, Equilibrium is quite pretty in its action, very symmetrical. But also like his face, the fact that I just gave away a meaty part of the climax should be easily disconnected from whether or not you should still watch Equilibrium. You should: it’s all as simultaneously bonkers and well-mannered as the moment in which Taye Diggs’ face slides off the front of his head like salami from a meat slicer. —Dom Sinacola

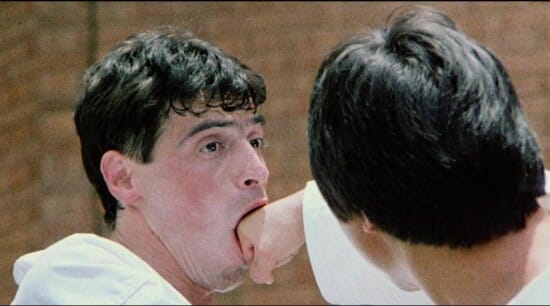

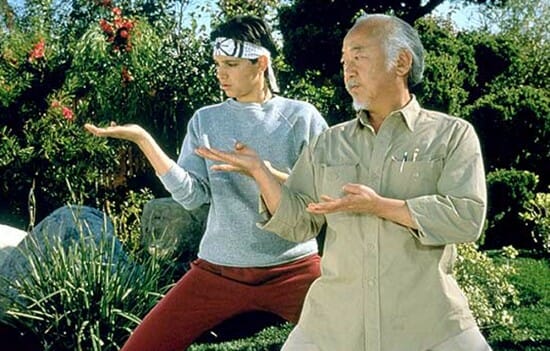

80. The Karate KidYear: 1984

Director: John G. Avildsen

Ralph Macchio’s crane-legged Karate Kid would become an icon of the ’80s, as would Pat Morita as Mr. Miyagi, the sensei who trains the bullied Daniel LaRusso in martial arts. Although many of the scenes can feel a little worn and trope-laden, that’s mostly due to how much the film has been copied in the years since its release. It was the sort of feature that defined karate to an entire generation of young kids and must have inspired countless dojo openings and yellow belt ceremonies. It also features one of the great villains of ’80s cinema in the merciless Cobra Kai coach, Sensei John Kreese: “Sweep the leg, Johnny.” —Josh Jackson

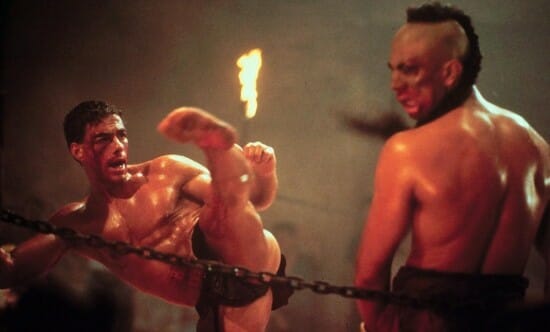

79. KickboxerYear: 1989

Director: Mark DiSalle and David Worth

Like an unofficial sequel to 1988’s Bloodsport—but more a refining than a new adventure for that movie’s Frank Dux (Jean-Claude Van Damme)—Kickboxer is meatier, meaner, and sweatier than its comparatively tame predecessor. In the course of two years, Van Damme had starred in four action films, his less dependable two (Black Eagle and the confounding Cyborg) sandwiched between a pair of nearly identical films that pretty much soldered Van Damme’s fully-formed cinematic persona to his blocky, unblemished, well-bred Belgian forehead. It could be said that every Van Damme movie is pretty much one Van Damme movie, but Kickboxer claims that this idea isn’t such a bad one. If time is just a flat circle, let us relish the moment that Van Damme’s mutantly macho Kurt Sloane high-kicks the smarmy grin off the face of psychotic rapist Tong Po (Michel Qissi)—over and over and over again, as if it were only the first time. —Dom Sinacola

78. The Cave of Silken WebYear: 1967

Director: Ho Meng Hua

The “martial arts” genre has room for all kinds—serious and light-hearted, mature and family friendly. The Cave of Silken Web is technically supposed to be the latter, but wow, is it surreal to watch. A take on the famous “Journey to the West” story (which will come up again on this list), it’s about a monk on a long journey with his protectors, who include a pig man and the “Monkey King,” who looks pretty much as you would expect. The villains are spider demons who take the guise of attractive women and scheme to achieve eternal life by eating the pure flesh of the monk. There’s even a musical number by the spider women about how they can’t wait to eat this guy—pretty damn weird stuff, but oddly compelling. Like many other Shaw Brothers films of the period, the production values are actually pretty high and the color photography really pops. —Jim Vorel

77. Best of the BestYear: 1989

Director: Bob Radler

A hilariously sincere American cheese-fest, Best of the Best is essentially Cool Runnings, except the stakes are a life-and-death martial arts tournament against that evil foreign superpower we all love so much: Korea. It’s a story about an American team of martial artists thrown together from the dregs of society—“they’re a ragtag bunch of misfits!” There’s the street fighter from Detroit, the guy who’s a cowboy for some reason, the grizzled veteran/widower, and, of course, the young kid seeking vengeance for the death of his brother at the hand of the Korean leader, who, I shit you not, wears an eyepatch while fighting. The ending in particular is pure schmaltz: Rather than give in to hate and kill his opponent in the ring, our hero lets Team Korea win to keep his honor. And then the Koreans apologize, hand the Americans their medals, and everyone hugs it out. With James Earl Jones as the coach who yells stuff! —Jim Vorel

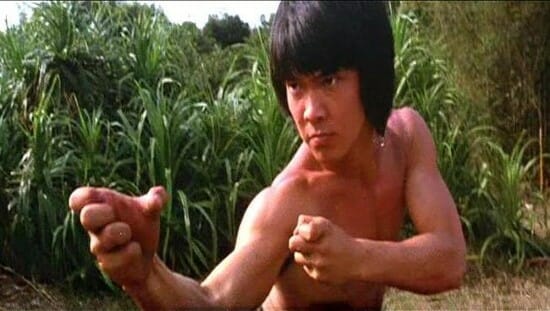

76. Dragon LordYear: 1982

Director: Jackie Chan

By 1982, Jackie Chan was fairly well known to Hong Kong audiences as an ascendant performer who, along with the likes of Sammo Hung, was introducing a new dimension of comedic martial arts films. An absolutely superior athlete and stunt coordinator, he had already starred in more traditional kung fu comedies such as the original Drunken Master, and was now experimenting with expanding his stunt action sequences in a period setting. The fanatical director brought an insane work ethic to projects such as Dragon Lord, which quite honestly features one of the more silly, childlike premises in the genre’s history: Chan’s character gets mixed up with a bunch of thugs after the kite he’s flying accidentally gets away from him and lands in their headquarters. It’s absolutely absurd, but the stunt work is Chan at his hyperkinetic best. —Jim Vorel

75. Dragon: The Bruce Lee StoryYear: 1993

Director: Rob Cohen

The details of Bruce Lee’s life tend to be contentious, and his philosophies interpreted to serve the ends of whomever is examining them, but Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story does a good job of simply celebrating the life of the most famous martial artist of all time. Jason Scott Lee is inherently likable as Bruce, in a story that spans from his childhood to his time in the United States and breakthrough on American television in The Green Hornet. The film is unfortunately tinged with tragedy, both from Lee’s death at 32 and that of his son Brandon at 28 on the set of The Crow, only two months before its release. Nevertheless, it was received well and manages to come off as more of a loving tribute than an attempt to profiteer on Lee’s name. —Jim Vorel

74. Dance of the Drunk MantisYear: 1979

Director: Yuen Woo-ping

Sequel structure wasn’t all that well-defined in kung fu cinema, and it was sometimes difficult to tell which films were supposed to be direct references to others, especially for American audiences. Case in point: Dance of the Drunk Mantis is essentially a sequel of sorts to the classic Drunken Master, not because Jackie Chan’s character is in it but because of the returning Yuen Siu-tien, who played his master, Beggar So. Turns out, this guy ran out on his family, and he returns to find a new, adoptive son called “Foggy.” When a challenger shows up using an imposing “Drunk Mantis” style and threatens Beggar So, Foggy has to learn an entirely new style of kung fu referred to as “sickness boxing” to counter the movements of the unpredictable, drunk-style fighters. It’s a classic showcase of drunken kung fu movements , which always strike a beautiful balance between bawdy humor and delicate ballet. —Jim Vorel

73. The Last DragonYear: 1985

Director: Michael Schultz

The Last Dragon is the funniest martial arts movie you’ve likely never seen, an outrageous blend of kung fu and blaxploitation movie tropes fused into the tale of Bruce Leroy, the titular last dragon. Underappreciated in its day as a hilarious satire on multiple genres, the film has now become a bona fide cult classic, especially for the amazing villain Sho’Nuff, the self-proclaimed “Shogun of Harlem.” There’s no other way to say it: Sho’Nuff is one of the greatest film villains of all time. As a style icon and source of one-liners, few can compare. There’s absolutely nothing serious about The Last Dragon, but for students of the genre it’s a magical diversion for a movie night with friends. —Jim Vorel

72. UnleashedYear: 2005

Director: Louis Leterrier

In his second go directing a script penned by futurist action maestro Luc Besson, Louis Leterrier strikes absurd gold by telling the story of a street-fighting orphan (Jet Li) who’s raised by the mob to be an attack dog. Wrapping an ageless Li’s neck with a dog collar and watching the veteran Hong Kong star medievally pound the living daylights out of one unfortunate henchman after another, Letterier casts Bob Hoskins as the mob boss behind Li’s enslavement; Hoskins, bless him, is totally devoted to the boundless evil his Irish character affords him, making Jet Li’s fight—literally—for his freedom a truly odd thing to behold. In classic Besson fashion, unrelenting fight scenes are punctuated by painful schmaltz, but what compensates for a lagging middle section—in which Li learns how to be a real person from a too-well-suited Morgan Freeman (playing a wise, old blind man…seriously)—is Li’s surprisingly touching charm as the socially awkward but physically unmatched bearer of tragic circumstances. Of course, in the wrong light, the whole thing could’ve been an offensive fluke, but the absolute commitment of everyone involved elevates Unleashed to the status of overlooked, undeniably bat-shit action classic. —Dom Sinacola

71. Clan of the White LotusYear: 1980

Director: Lo Lieh

Clan of the White Lotus is pure, vintage kung fu, and excellent, archetypal film that is only bumped down the list slightly because it’s practically a remake of the earlier Executioners from Shaolin in most respects. The great Gordon Liu stars as a monk out for revenge (naturally), but it’s really the villain, Priest White Lotus, who steals the show. Portrayed by director Lo Lieh, he projects such a perfect sense of menace and sheer invincibility that Liu has to train in multiple new and inventive styles to even stand a chance. It’s a great film of progression, as the repeated battles between the two show the evolution in Liu’s technique as he attempts to assail the stone wall that is White Lotus. Visually, it looks exactly like what a novice would picture in his or her head when someone says “kung fu movie.” —Jim Vorel

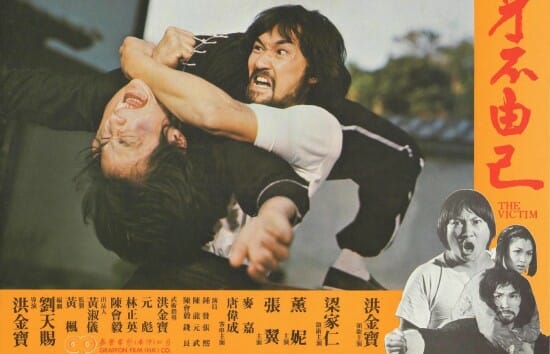

70. The VictimYear: 1980

Director: Sammo Hung

Kung fu movies can sometimes come off as weirdly compartmentalized between humor and really dramatic, serious action. Such is the case with Sammo Hung’s The Victim. In typical Hung fashion, he plays a comedic character named “Fatty” who indentures himself to a brave martial artist after the guy bests him in combat. Fatty is merely a sidekick/comic relief, however—his master is the film’s true protagonist, and his own story is much more melodramatic, revolving around the woman that both he and his adoptive brother, a gang leader, desire. When she commits suicide in an attempt to end the fighting and keep everyone safe, they end up in an epic, knock-down, drag-out kung fu battle that ends with a rather spectacular finishing move—a pro wrestling-style giant swing. It’s an especially gritty, hard-hitting confrontation. —Jim Vorel

69. Last Hurrah For ChivalryYear: 1979

Director: John Woo

Before he was iconically known for the likes of Hard Boiled and the “gunkata” genre, director John Woo dabbled in classical kung fu and wuxia pictures. Many of the themes are the same, though—killers for hire, deception, organized crime and revelations about who is really working for whom. Here though, instead of cops and robbers it’s swordsmen and kung fu masters. Last Hurrah For Chivalry is definitely a film that leans on its stuntwork and choreography rather than any story of particular interest, but lovers of stage combat will certainly appreciate the fast and furious swordplay. The slashing sound effects are beyond ridiculous, but that’s to be expected, and the creative use of props elevates these swordfights to a sublime level. —Jim Vorel

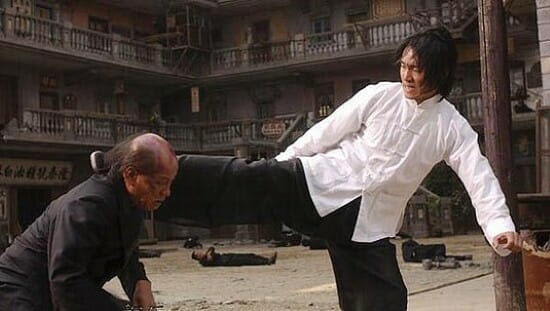

68. Kung Fu HustleYear: 2004

Director: Stephen Chow

Stephen Chow is probably the biggest name in martial arts comedy since the days of Sammo Hung, and Kung Fu Hustle will likely remain one of his most well-regarded films both as a director and performer. Gleefully kooky, it combines occasional song and dance with extremely exaggerated kung fu parody in telling the tale of a young man who ends up overthrowing a large criminal organization, the “Deadly Axe Gang.” This is not a complex film—rather, it’s simply intended as popcorn entertainment at its most absurd. The action has no basis in reality, being closer to a real-world depiction of Looney Tune physics. The characters are broad pastiches and references to famous actors from the genre’s history abound. With comedy that teeters decidedly on the juvenile or inscrutable side, it’s a film that some will dismiss off-hand, but Chow’s style has always and will probably always be “entertain first, make sense later.” That’s what he does, and he does it better than anyone else. —Jim Vorel

67. 2 Champions of ShaolinYear: 1980

Director: Chang Cheh

Another Venom Mob film by Chang Cheh, except this one comes with a Shaolin twist. It’s one of the few Venom films to star burly Lo Mang as the primary hero, although he still perishes at the end as he seemingly always does in their films. The plot revolves around two warring clans: the honorable Shaolin fighters and the deplorable Wu Tangs, who use seemingly magical throwing knives that bend the hell out of the laws of aerodynamics. A convoluted series of alliances and allegiances are forged and tested, leading to a final fight that goes full Hamlet and kills pretty much everybody. It’s bloody good fun from the Shaw Brothers with a well-balanced variety of action elements and styles that don’t run too strongly in any one direction. —Jim Vorel

66. Mr. VampireYear: 1985

Director: Ricky Lau

This flick will, within moments, have you checking your drink to be sure you haven’t been drugged. Responsible for first bringing the so-called jiangshi subgenre into vogue, Mr. Vampire is an utterly bizarre but compellingly original creation that blends a classic kung fu movie with horror and elements of ancient Chinese folklore/mythology. The vampires in question (there’s more than one) are the Eastern variety of “hopping” vamp, which move by holding their arms straight out in front of them and jumping around with little bunny hops. Oh, and you can repel them by holding your breath. The movie is a cinematic fever dream, which a few seconds of the trailer, with its flying heads and hopping vampires, should make abundantly clear. —Jim Vorel

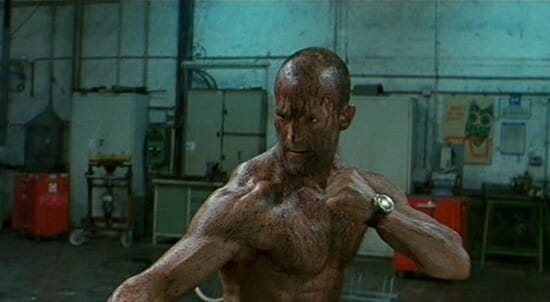

65. The TransporterYear: 2002

Director: Louis Leterrier

Before The Transporter, Jason Statham was more cockney thug than lithe action beast, but after The Transporter came the frenetic shitstorm of Crank, followed by War, which pitted him against none other than Jet Li—so we can pretty much thank Louis Leterrier for believing in Statham’s martial arts prowess enough to give him both the right playground to inhabit and the license to take it apart. Imagine him a gruffer cousin to Jean-Claude Van Damme, just as given to finding himself shirtless, but more apt to preserve his mopey loner status—at least until some beautiful upstart maiden enters his life and throws herself at him. In that sense, Statham’s Frank Martin is the ideal distillation of Eastern martial arts archetypal heroes into the glossy neons of a Western action spectacle: soundless, sexless and merciless, his physicality leaves no room for personality. Watch only the scene in which Frank tip-toes on bicycle pedals through an oil slick, roundhousing every dumb face in his impressive radius to propel body after body away on inky skids, to witness a lovable killing machine portrayed in as empirical—as perfect—a way as we can ever expect out of The Transporter’s more traditional Asian forebears. —Dom Sinacola

64. BloodsportYear: 1988

Director: Newt Arnold

There are tomes to be written and classes to be taught on the perplexing existence of Bloodsport, but perhaps the film is best summarized in one moment: the infamous Scream. Because in these 40 seconds or so, the heart and soul of Bloodsport is bared with little concern for taste, or purpose, or respect for the physically binding laws of reality—in this moment is a burgeoning movie star channeling his best attributes (astounding muscles; years of suppressed rage; the juxtaposition of grace and violence that is his well-oiled and cleanly shaven corporeal form) to make a go at real-live Hollywood acting. Although Bloodsport is the movie that announced Jean-Claude Van Damme and his impenetrable accent to the world—as well as serving as the crucible for (seriously) every single plot of every Van Damme movie to come—it’s also a defining film of the decade, positioning martial arts as certifiable blockbuster action cinema. Schwarzenegger and Stallone? These were beefy mooks that could believably be action stars. Van Damme set the bar higher: his body became a better and bloodier weapon than any hand-cannon that previous mumbling, ’80s box-office draws could ever wield. —Dom Sinacola

63. Sister Street FighterYear: 1974

Director: Kazuhiko Yamaguchi

Sister Street Fighter is the second sequel to Sonny Chiba’s The Street Fighter, and in truth it may actually be more exciting, if not more iconic. Chiba appears in the film in a supporting role instead of as his Terry Tsurugi character from the first two films, but the actual star of the show is Sue Shiomi as Tina, a young woman searching for her missing brother, a drug agent who goes missing while investigating a criminal organization. It’s a classic team-up as Chiba and Shiomi’s characters infiltrate the organization and set up a final battle with the villain, who uses a claw weapon in seeming imitation of the villain from Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon. Simply a satisfying story with a fittingly high body count, it features a wide array of martial art styles in the villain’s stable of hired killers, which make for an action-packed conclusion. —Jim Vorel

62. Kung Fu PandaYear: 2008

Director: John Stevenson

Kung Fu Panda isn’t just a good movie—it’s a good kung fu movie. The title isn’t pandering, because the film truly respects its source material. Jack Black’s character may as well be Sammo Hung or Jackie Chan in one of his early roles. All of the classical elements are there—an obnoxious pupil who becomes a fighting machine. A team of (literally) animal-based martial artists with varying styles. An unbeatable, rampaging villain in the vein of the Ghost-Faced Killer from Mystery of Chessboxing. And a secret technique that the hero needs to learn in order to conquer that villain. It’s a funny, vibrant film as easily enjoyed by children as adults, and one that the adult viewers should feel no embarrassment for enjoying as much as they do. If you like classical martial arts filmmaking, Kung Fu Panda is probably the most faithful animated twist on the genre that anyone has pulled off so far. Too bad the same can’t be said of its overblown sequels. —Jim Vorel

61. Man of Tai ChiYear: 2013

Director: Keanu Reeves

It’s still a phrase that lodges in the throat: “Director: Keanu Reeves.” But for anyone who left John Wick loose-limbed and exhausted due to the sheer grace of Reeves’ action chops, it should come as absolutely no surprise that the man—the one and only Neo—can direct the fuck out of a martial arts movie. With little frills, barely a plot, a Tai Chi phenom in Tiger Chen (who also served as Reeves’ teacher and, for Kill Bill, Uma Thurman’s stunt double), a strong woman character who seems smarter than all the ’roided-out dudes beating each other senseless surrounding her, and Reeves’ ever-present sonic mangling of the English language, Man of Tai Chi is pretty much exactly what the title suggests: an exhilarating, inertial obsession both with movement as art as power and with those who wield it inimitably. Testament to Reeves’s intelligence as a self-didact who just wants to do right by those folks who put their trust in him over the course of his many-decade career, Man of Tai Chi is exactly what you most hoped for when you first saw who directed it. That it’s awesome is surprising—and it’s even better for that. —Dom Sinacola

60. Kiss of the DragonYear: 2001

Director: Chris Nahon

Jet Li was a Hong Kong superstar who came across the sea to America, likely with hopes of a Jackie Chan-like career trajectory in his mind. However, after a few poorly received American films such as Romeo Must Die, it became clear he probably wouldn’t be that sort of crossover star. Kiss of the Dragon brought things back down to Earth a bit, in a John Woo-style feature starring Li as a Chinese intelligence agent hunting for a drug lord in Paris. Of his American films, it probably relies the least on CGI or wirework, although some is clearly evident in what is likely the film’s most famous moment—when a pinned-down Li kicks a pool ball out of the pocket and again in mid-air to disarm a gunman. The rest of the action is fast-paced and violent, mixing gunplay and a greater than average prevalence of broken necks. —Jim Vorel

59. The Prodigal SonYear: 1981

Director: Sammo Hung

Another film directed by Sammo Hung, Prodigal Son reins in the comedy for once to present a unique story about privileged children and the price of true knowledge. Yuen Biao stars as Chang, the son of a wealthy man who believes himself to be a kung fu master. However, because he lacks any real skill, his father has clandestinely been bribing all of his opponents to lose. When the ruse is revealed, Chang must join up with a traveling circus troupe and its Wing Chun-employing leader to learn true kung fu. It’s a more mature turn from Hung, who co-stars as one of Chang’s tutors, and the action choreography is expansive, free-flowing and beautiful. With that said, the guy with no eyebrows still sort of creeps me out. —Jim Vorel

58. The Raid 2: BerendalYear: 2014

Director: Gareth Evans

Nearly five years in gestation, The Raid 2 feels like the exact kind of movie that Gareth Evans has always dreamed of making. Or…scratch that: this is the kind of movie that every fan of martial arts cinema has always dreamed of watching—the pure and unhindered manifestation of brutal hand-to-hand action shot with unrepentantly magnanimous scope. Where the original film exposed the world to a rapid-fire form of Indonesian martial arts called Pencak silat, The Raid 2 made that style of fighting the only key to survival in a society on the verge of total nihilism. Expanding from an occupied office building to the whole of the criminal underworld, The Raid 2 takes the surviving characters from the first film and pushes them toward a tragic and/or exhausted end. Practically every scene is the result of filmmaking bravura, but perhaps the most trenchant is one in which hero Rama (Iko Uwais), barely holding himself together after hours of fighting, walks slowly back through the now-quiet graveyard of defeated bodies he left in his wake not long before. It’s a humbling moment, that the calm after the storm is just a sad reflection on all the pain inflicted during the storm itself. Self-aware and yet unstoppable despite that, The Raid 2 is a new standard for action cinema. —Dom Sinacola

57. KnockaboutYear: 1979

Director: Sammo Hung

Knockabout is like the perfect template of a Sammo Hung movie: Simple, crowd-pleasing, good-natured and infinitely rewatchable, like martial arts comfort food. Hung directs and co-stars as a “fat beggar,” very much in the vein of Drunken Master’s Beggar So, without the intoxication. Really, though, Knockabout is truly the Yuen Biao appreciation film—one of the “Seven Little Fortunes” that included Jackie Chan and Hung, Biao is beloved by genre fans but not nearly well known enough to the wider world, which is a real shame. Like Chan, his lithe athleticism and comedic chops make him instantly likable, but in terms of physicality he might be an even more acrobatic (if not intimidating) fighter. Here, he’s training with Hung in order to hunt down the man who killed his brother (fresh idea!), but hey, it gives us an excuse for some great training sequences featuring monkey style kung fu and the amazingly acrobatic jump rope sequence. It’s the kind of thing you never see in modern martial arts films, and this kind of pure athletic showmanship is sorely missed. —Jim Vorel

56. Red CliffYear: 2008

Director: John Woo

When we think of John Woo, we tend to think of gun ballads and Chow Yun-Fat. We’re not wired to think of large-scale portrayals of warfare, much less period dramas set during the end of the Han Dynasty. Magnolia split the film more or less in twain for its U.S. release; you won’t find the full 288-minute version on Netflix Instant, but Red Cliff feels complete even with roughly half its content rotting on the cutting floor. This is a towering film, one that’s filled with allusion and metaphor, stratagem and scheming, sentimentality and philosophy, and eye-popping battle sequences that afford Woo plenty of room to harmonize historical accuracy with the signature flourishes that make him an action maestro. —Andy Crump

55. The Invincible ArmourYear: 1977

Director: See-Yuen Ng

The plot of The Invincible Armour is a bit on the inscrutable side, revolving around assassination and people being framed for various crimes, but none of that really matters because the majority is spent indulging in some cheesy kung fu goodness. The key technique here is “iron armour,” a method of hardening and toughening the body to shrug off blows. There’s lots of great training sequences and montages of both the heroes and villains employing these techniques, whether it’s dipping themselves in boiling water, headbutting spiked balls on chains or simply reclining onto spear points, which the trailer reminds us is “exciting and fantastic!” The fact that the villain’s single weak point turns out to be his groin makes for an especially hilarious conclusion that literally involves his junk being crushed …TO DEATH! Accompanied by helpful visual metaphors. —Jim Vorel

54. Snake in the Eagle’s ShadowYear: 1978

Director: Yuen Woo-ping

The directorial debut of influential director/choreographer Yuen Woo-ping, Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow was also one of Jackie Chan’s first starring roles, predating his star-making turn in Drunken Master. Chan plays an orphan adopted into a kung fu school, where he is abused and beaten up by the teachers and students regularly until a beggar teaches him snake-style kung fu. He then becomes a champion/defender of the school before being roped into a plot by eagle-claw kung fu practitioners to kill off all the snake-style users. In short, it’s classic kung fu stuff, very much about battles between iconic styles—mantis-style users also show up for a fight at one point. Chan hadn’t quite gotten into his comedic period yet, and it’s fascinating to see the young performer (24 years old at the time) at his physical best, but still sitting on plenty of untapped potential. —Jim Vorel

53. ShaolinYear: 2011

Director: Benny Chan

It’s pretty rare that one can look back on the history of a genre, pick out a classic style of film, and say, “Let’s lovingly recreate it as it would have been made in the modern era.” Look at horror: How well did that work for Van Helsing or The Wolfman? But Shaolin somehow manages to pull that off, a modern revitalization of the classic “Shaolin temple” film subtype. It integrates tropes, such as a man on the run begging entry into the temple, with the expected training sequences established by The 36th Chamber of Shaolin. But it also gets the best it can from its modern effects budget, and features Jackie Chan in the most sensible way one can use him in the 2010s, which is as fluid comic relief. This is the kind of premise that could have simply felt like nostalgia or a cash-grab, but is pulled off with excitement and reverence in equal measure. —Jim Vorel

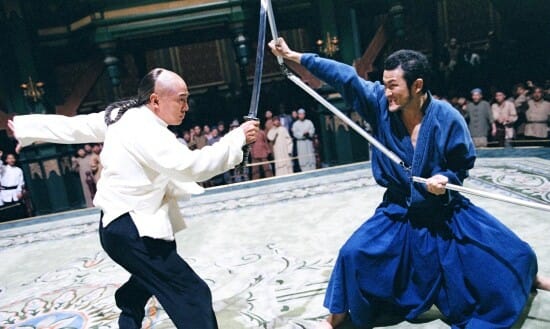

52. FearlessYear: 2006

Director: Ronny Yu

After his somewhat underwhelming Hollywood period, Jet Li returned to Hong Kong to pull off his last great historical kung fu film, Fearless. One can tell that the story of Huo Yuanjia, a martial artist who triumphed over a variety of international fighters at a time when China’s national identity was flagging, is an important one to him. Fittingly, Li imparts one of his best acting performances to the film, which tells the tale of how Yuanjia learned his skills and realizes he must stand up for his nation’s reputation. The film ends with a great, tragic fight sequence as Yuanjia takes on an honorable Japanese swordsman but is simultaneously poisoned by scheming aristocrats. The choreography is beautiful but appreciably restrained in reality, which was rare to see in a high-budget film in the years following Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. —Jim Vorel

51. ChocolateYear: 2008

Director: Prachya Pinkaew

Chocolate is a pretty odd premise that succeeds because the action is just so good. One might summarize it thusly: “It’s like Rain Man, except with more muy thai.” As in, the lead character is an autistic savant, except instead of counting toothpicks, her talents mostly lay in kicking people in the face. Casting is critical to its success; lead Yanin “Jeeja” Vismistananda is an ostensibly adorable waif, which makes her appear as a most unlikely butt-kicker. After a childhood spent mnemonically absorbing martial arts movies, however, she turns into a tool of vengeance unleashed upon the gangster threatening her mother. The fight scenes are over-the-top ridiculous but thankfully wireless, which makes for a stylish, exuberant film. —Jim Vorel

50. Executioners From ShaolinYear: 1977

Director: Lau Kar-leung

If you remember the story of Pai Mei, the white lotus, that David Carradine tells to Uma Thurman around the campfire in Kill Bill, then you essentially know the story of this film. Tarantino’s double-film is filled to the brim with references to classic kung fu cinema, not least of which is Gordon Liu’s Pai Mei character, who is an absolutely iconic villain in Executioners from Shaolin. A true monster, he butchers the monks of the Shaolin Temple with his nigh-invincibility, and is only brought down eventually by characters who have trained for decades specifically to find his few vulnerabilities. Pai Mei’s mastery of his bodily functions, referred to as “internal kung fu,” make him one of the most imposing villains in the history of the genre, and make this film a classic element of the genre’s lore. Bonus: Gordon Liu appears as a badass monk in the beginning who sacrifices himself against a small army of fighters to help his Shaolin brothers escape. —Jim Vorel

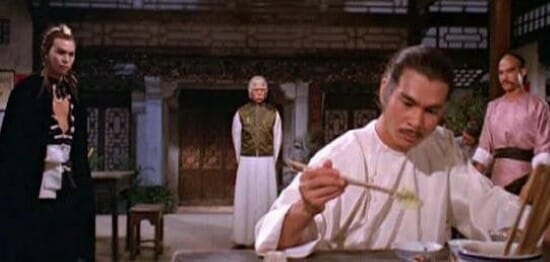

49. 3 Evil Masters, AKA The MasterYear: 1980

Director: Chin-Ku Lu

This is a film that feels a bit smaller in scope that some of the other Shaw Bros. epics on the list, with a smaller overall cast of characters and a bit less pageantry, but the story and action are both wonderful. The plot concerns a kung fu school being taken over by the titular three evil masters, each of whom has weird, distinctive stylistic flourishes. The protagonist is your typical young pupil who needs to learn a variety of techniques if he’s going to set things right at the school. A variety of dependable, familiar performers appear, particularly Chen Kuan Tai, who has a great early scene where he fights all three of the evil masters at once. I particularly love the guy in green, who uses his long braid of hair as a whip throughout the fight. Dude smashes through a table with his hair! Watch that clip and simply appreciate the long, uninterrupted take that begins at 3:30, it’s a thing of beauty. —Jim Vorel

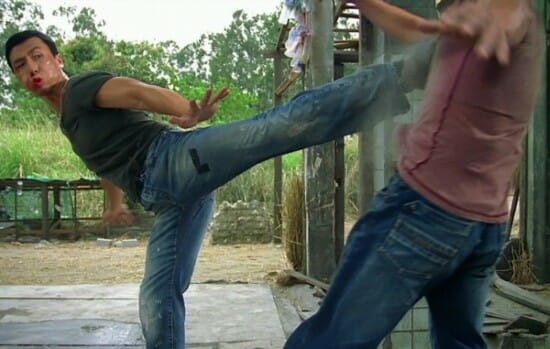

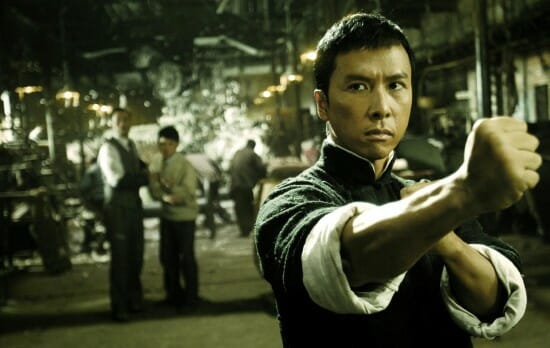

48. Kill Zone – SPLYear: 2005

Director: Wilson Yip

“SPL” stands for San Po Lang, three characters from Chinese astrology that, depending on their alignment in the heavens, can foretell both good and evil tidings. So proceeds Kill Zone, a prototypical Hong Kong crime flick that, like any salient martial arts hybrid post-2000, devolves into the shady moral gray of umpteen different action genres to prove a point about the malleable nature of our modern moral compass. Namely: all signs point to nothing—no hope, no love, no redemption; violence only begets more violence, and every action has an equal but opposite reaction. It’s no major revelation plot-wise, but when director Yip pulls in veteran Sammo Hung to, despite the girth of age, weave circles of devastation around thugs half his age, everything feels exactly as it should. Then, cue Donnie Yen, who will later play the definitive Ip Man, here a whirlwind of limbs in a brutal knife vs. baton alley fight. In its final moments, Kill Zone’s scorched earth policy leaves only the innocent alive; maybe this is how every martial arts movie should end. —Dom Sinacola

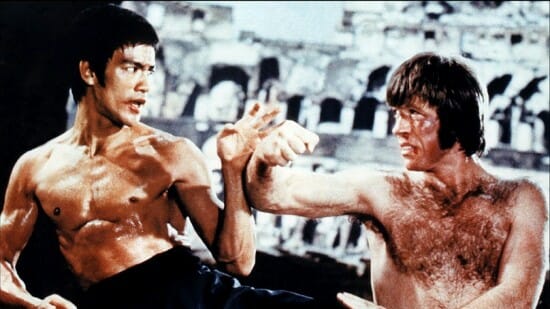

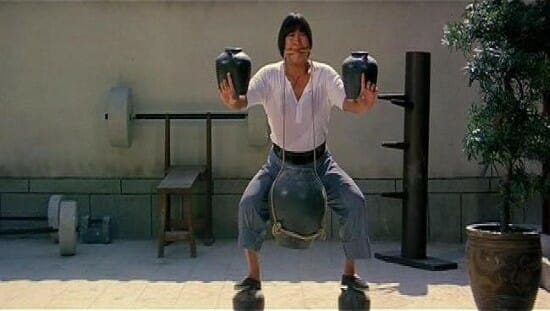

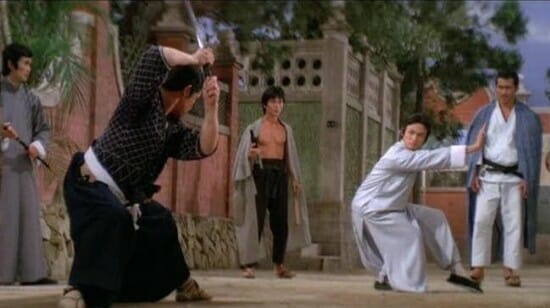

47. Way of the Dragon, AKA Return of the DragonYear: 1972

Director: Bruce Lee

Way of the Dragon stands as the only film that Bruce Lee ever finished directorial duties on, passing away before he could complete The Game of Death or the co-credit he might have shared on Enter the Dragon. It stands, therefore, as perhaps the most accurate and complete piece of work that Lee personally envisioned, a story about a Hong Kong fighter who travels to Rome in order to protect a family restaurant being threatened by the mob. As one would expect, it has some great fights, but nobody has quite the same presence on camera as Lee. If there’s one thing most viewers would take away from this one today, it’s the fact that this film contains one of the holy grails of martial arts battles: Bruce Lee vs. Chuck Norris, the final opponent, which takes place among the ruins of the Roman Colosseum. That classic fight is no doubt worth the price of admission alone—just feel the tension as both of them warm up and crack their knuckles before the battle begins. —Jim Vorel

46. Five Fingers of DeathYear: 1972

Director: Chang-hwa Chung

Enter the Dragon is often the martial arts film cited as being the start of the kung fu craze in America, but in reality it was Five Fingers of Death that kickstarted the genre in the U.S. a year earlier as an unexpected drive-in hit. As such, the dubbed version at least is a little more naive in its presentation and attitude toward the martial arts, treated with a sort of aloof, mystic reverence. At it’s core though, there’s an excellent story here, starring the great Lo Lieh as a young pupil who shuffles between masters as he attempts to learn the necessary skills to defeat a local tyrant and win the hand of the girl he loves. It proved extremely influential—once again, Kill Bill borrows elements here, in particular its instantly recognizable battle music, which was itself lifted from the 1967 TV series Ironside. Perhaps most importantly, films like this one paved the way for martial arts cinema to soon explode into crossover popularity in the U.S., with Bruce Lee as the standard-bearer. —Jim Vorel

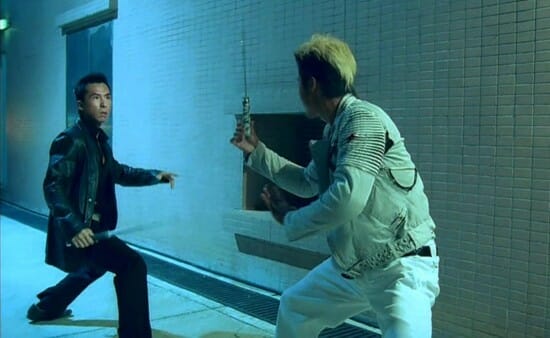

45. Flash PointYear: 2007

Director: Wilson Yip

Flash Point could probably have gotten away with spending its whole running time simmering through its central cat-and-mouse crime yarn, so long as it still ended with Donnie Yen and Collin Chou beating the tar out of each other. Theirs is a brawl for the ages, a knock-down, drag-out scrap between two titans of the martial arts genre that holds back nothing in the brutality department. Luckily for us, Wilson Yip makes the rest of Flash Point just as propulsive and exciting as its climax, but the film’s real draw lies in seeing its two biggest stars lock horns in one cataclysmic struggle. —Andy Crump

44. Journey to the West: Conquering the DemonsYear: 2013

Director: Stephen Chow and Derek Kwok

Every list of this nature needs a lot of Chow. Although the Hong Kong director’s Western breakthrough, the bonkers Shaolin Soccer, gives you a good idea of what’s on the director’s mind, the even bonkers-ier Journey to the West is a better place to start. Monumentally popular in China, breaking all-time box office records (even beating out Transformers 4, so you know this shit means business), Journey is based on a Chinese literary classic of the same name, but saturated with Chow’s now infamous wit, slapstick and barely containable glee at the possibility of fantasy filmmaking. Every scene is an elaborate tour de force of stunts and battles and exaggerated athleticism—just like every scene in every film of his to come before—but Journey takes that extra step to imbue its traditional genre tropes with grotesquerie and phantasmagorical imagination, transforming a pretty basic story about one monk’s path to enlightenment into Terry Gilliam’s wet dream, replete with pig monsters and monkey spirits and steampunk and practically everything in between. So much more than a martial arts flick, this feels like a super-gifted filmmaker doing exactly what he was born to do. —Dom Sinacola

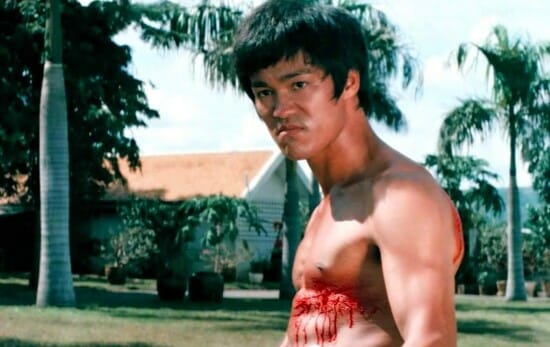

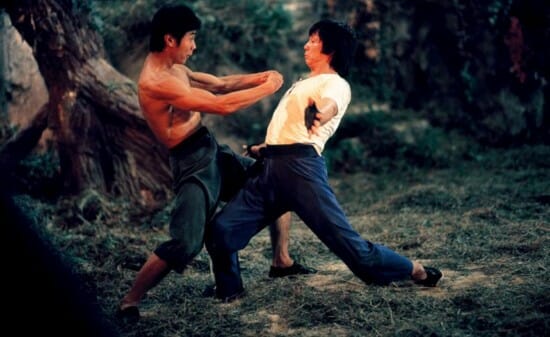

43. The Big Boss, AKA Fists of FuryYear: 1971

Director: Lo Wei

This is where it all started for a young man named Bruce Lee, his first starring vehicle in a Hong Kong action movie. Set in contemporary time, this isn’t some Shaolin temple period piece but a pretty grimy, modern crime movie that just happens to feature some martial arts. James Tien was ostensibly supposed to be the film’s star power, but it was clear that Bruce Lee had a magnetism that made him lightning in a bottle—you can’t look away when he’s on screen. The action isn’t quite fully developed, but you can just see the raw, seething potential in him, both as an actor and the most famous martial artist who’s ever lived. The film is more than a little goofy and its low-budgetness can make it a little bit tougher to watch today, but it’s worthwhile to see the birth of the legend. —Jim Vorel

42. The Brave ArcherYear: 1977

Director: Chang Cheh

The Brave Archer is a true martial arts epic by Chang Cheh and the Shaws, taking full advantage of a large budget and access to expansive, lavish sets. Long and sprawling, it’s pretty hard to sum up in only a few sentences, but suffice to say it centers around a young man played by the great Alexander Fu Sheng who searches for several parts of a mystical kung fu manual while also competing against another suitor for the affections of a woman he has loved his whole life. There are dozens of characters, and the film feels a bit like a “best-of” genre piece, with many recognizable faces who pass through and play bit parts. Probably best-suited to viewers who are well-steeped in the kung fu genre in particular, it’s an iconic adventure film that spawned multiple sequels before the tragic death of Fu Sheng in a car crash at only 28 years old. He was truly a talent taken before his time, but The Brave Archer stands as a testament to his skills as a performer. —Jim Vorel

41. The MatrixYear: 1999

Director: Andy Wachowski and Lana Wachowski

There is not much to say about the film that made cyberpunk not stupid, or that made Keanu Reeves a respectable figure of American kung fu, or that finally made martial arts films a seriously hot commodity outside of Asia. The Matrix is—next to the Wu-Tang Clan—what proved to a new generation that martial arts films were worth their scrutiny, and in that reputation is bred college classes, heroes’ journeys, and impossible expectations for special effects. While there are plenty better, there is no movie in the canon of martial arts films bigger than The Matrix, and even today we still have this film to thank for so much of what we love about modern kinetic cinema. This is our red pill; everything else is an illusion of greatness and everything else is an allusion to what the Wachowskis accomplished. —Dom Sinacola

40. Legendary Weapons of ChinaYear: 1982

Director: Lau Kar-leung

This film is a bit of a storytelling Gordian knot, but all of the interconnected plots means tons of colorful characters and combat. The main plot revolves around a group of “spiritual boxers” martial artists attempting to train their bodies to resist the bullets of Western imperialist guns. These villains are also hunting down former members of the group who have since admitted that stopping a bullet by flexing your abs probably isn’t possible. The real attraction is the incredible array of styles: Ti Tan the impenetrable monk played by Gordon Liu, Maoshan “magic boxers” and more. And as if that’s not enough, you also have the reason for the title: This film highlights the styles and uses of traditional Chinese weaponry better than any other on the list. There’s 18 different weapons in total that are featured, many during the epic final scene where the hero and villain cycle through all of the legendary weapons as they probe the strengths and weaknesses of each bit of armament. It’s one of the only scenes of its kind, and it’s magnificent. —Jim Vorel

39. Dragon Gate InnYear: 1967

Director: King Hu

An influential film that one might call the birth of the modern wuxia epic, Dragon Gate Inn was actually made in Taiwan, despite being set in historical China. It’s a story of family, as several orphaned children of a deposed general are on the run from a band of hired killers. As they flee for the country’s borders, a trap is waiting for them at the Dragon Gate Inn. But when a brother-sister team of martial artist allies arrive, they help even the odds for the refugees. The action is stylish and heavy on the swordplay. I’ve always been amused by this scene in particular, when a bevy of four swordsman try to overwhelm the old master by running around him in a circle in order to disorient him. —Jim Vorel

38. Wing ChunYear: 1994

Director: Yuen Woo-ping

Michelle Yeoh would become well-known six years later with the release of cross-cultural smash hit Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, but she was a star in martial arts cinema from the 1980s onward, and Wing Chun is one of the best overall star vehicles for her great physical (and comedic) talents. Tonally, it’s sort of an unusual film, as much romantic comedy as it is martial arts movie, but without sacrificing the gravitas of the action sequences. It manages to be both charming, as the story of a country woman protecting her village, and a thrilling collection of set-pieces largely practical in their special effects. It’s hard not to fall in love a little bit with Yeoh by the end—she’s as beautiful as she is talented. —Jim Vorel

37. Riki-Oh: The Story of RickyYear: 1991

Director: Lam Nai-choi

Adapted from a Japanese manga and one of the few films on this list that should definitely not be watched in its original language, Riki-Oh is a hallucinatory smorgasbord of flying viscera and exploding bone fragments—either a deadpan attempt to translate gratuitous comic book violence to the screen, and thereby comment on the kind of jading culture perpetuated by martial arts media, or just a movie made by a seriously crazy person. My bet’s on the latter, and only that, because there is palpable, irrepressible glee in the punching open of an obese man’s stomach, or the vice-like obliterating of another man’s skull, or how, when another fighter blocks Ricky’s jab, that poor guy’s fist splinters into a fine red mist spritzed between shards of ulna. It is all—all of it—just totally fucking insane: watch with your friends, laugh with your friends, cheer with your friends when, at the very end, Ricky—spoiler alert—through the sheer power of his inhuman awesomeness, punches down a 30-foot concrete wall. Because that happens. —Dom Sinacola

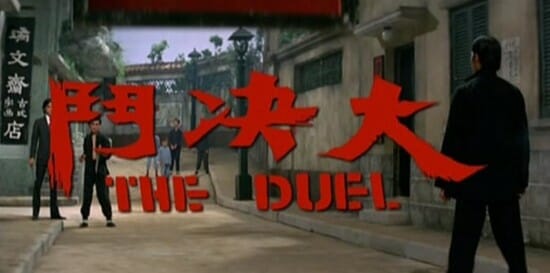

36. The DuelYear: 1971

Director: Chang Cheh

In the U.S., this early Chang Cheh feature was known as Duel of the Iron Fist, and although badass-sounding, it’s blatantly inaccurate, as the amount of traditional kung fu in this film is on the light side. Rather, The Duel is something more unique, a moody and well-acted crime drama that still has tons of bloody martial arts action sequences, many of them being knife fights. The film features perhaps the two biggest stars of the day, Ti Lung and David Chiang, as the participants in the titular duel, and this was a pretty big deal. Both had typically played heroes in the past, and both had been paired together as allies. For the Chinese audience, seeing the two of them finally come to blows in a duel to the death was a bit like watching Macho Man Randy Savage turn against Hulk Hogan and break up the Mega Powers. David Chiang alone kills nearly 100 people in this freaking movie. —Jim Vorel

35. Come Drink With MeYear: 1966

Director: King Hu (with Sammo Hung)

With a female protagonist (Cheng Pei-pei) at the head of an army of warrior women and the Shaw Brothers’ stamp early on in the production company’s run, Come Drink With Me not only broke the wuxia mold, it practically created it. Without the film, there would have been no Kill Bill (Quentin Tarantino has even been rumored for years to have a remake in his docket); in fact, without this film’s meager success in the U.S., later bolstered by the Weinstein Brothers commitment to bringing martial arts classics to cult-inclined Western audiences, there are few other films of its ilk that would have ever been embraced outside of China and Hong Kong. Achingly tender in moments, with fight scenes that more resemble sophisticated, choreographed dance than realistic brawls, the influence of Come Drink With Me can’t be overstated. Even if you’ve never seen it, when you think of martial arts film, you think of something akin to this. —Dom Sinacola

34. Swordsman 2Year: 1992

Director: Ching Siu-tung

Colorful, complex and engaging, Swordsman 2 is a great star vehicle for a young Jet Li and perhaps the best Chinese wuxia movie of the ’90s in the classical sense. It’s a sweeping historical drama with a rather confusing plot, but suffice to say there are multiple clans vying for possession of a scroll—total macguffin stuff, really. It’s a great excuse to get a bunch of martial artists together and let them have at it in really dramatic, superpowered, ham-handed ways: I love when the ninjas show up and attack the camp at night by hurling both throwing stars and SACKS FULL OF SCORPIONS at their opponents. There’s tons of flashy swordplay as you would expect in a great wuxia film, and lots of wire-aided fight scene craziness. Martial arts fans tend to praise films almost exclusively for realism and real acrobatics, but Swordsman 2 is a great example of the mystical artistry that good wire-work does bring to the film when used to set a visual aesthetic properly. —Jim Vorel

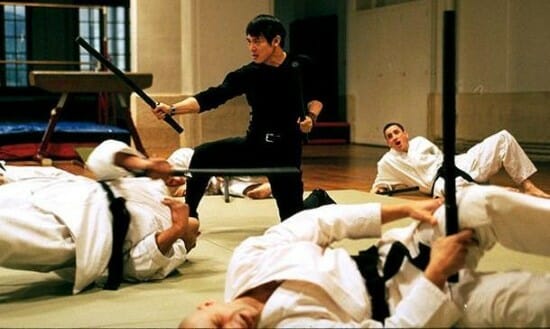

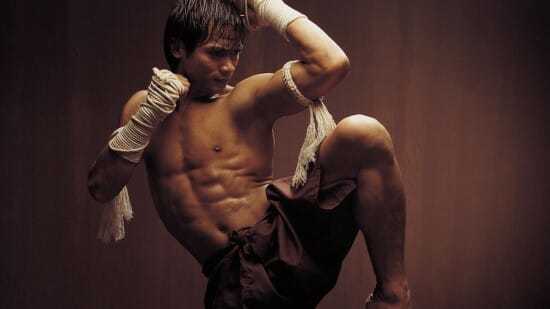

33. Ong-Bak: The Thai WarriorYear: 2003

Director: Prachya Pinkaew

After a decade-long trend toward ever more prominent wire work and special effects, Tony Jaa’s 2003 Thai star vehicle Ong-Bak was a return to insane stunts (all performed by Jaa himself) and hard-hitting action. Featuring an utter lack of both wire-fu and CGI, Ong-Bak is a jaw-dropping viewing experience. Although the story is little more than an excuse to trek across Thailand (both Bangkok and the countryside) in a constant stream of crazy chase sequences and even crazier fights, the film is so unashamed of being exactly what it is and nothing more that one can’t help but smile and fully resign to being blown away by some of the most impressive displays of martial arts—and physicality in general—to hit the screen in the new millennium. —K. Alexander Smith

32. The Raid: RedemptionYear: 2011

Director: Gareth Evans

When future generations look back upon the beginning of the 21st century and seek a way to understand the claustrophobia and fear that defined so much of our popular media of the time, let them look upon The Raid and weep. Essentially one extended action set-piece, paced with super-human precision to both incite and then maximally exploit one’s heightened dopamine levels, The Raid leaves no headspace for hesitation—once you’re in, you’re at its mercy, and the film’s only relief awaits at the top of an apartment block ruled by one of Jakarta’s scrappiest, psychopathic-iest crime bosses. The Raid is what martial arts cinema looks like in our young century: bleak, dystopian and hyper-violent. This is brutality at its barest. —Dom Sinacola

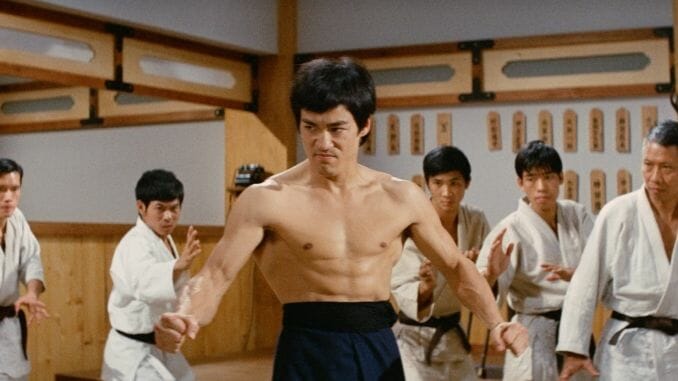

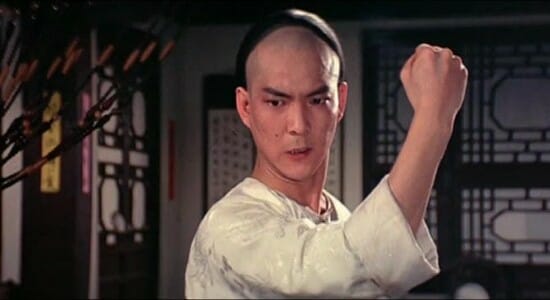

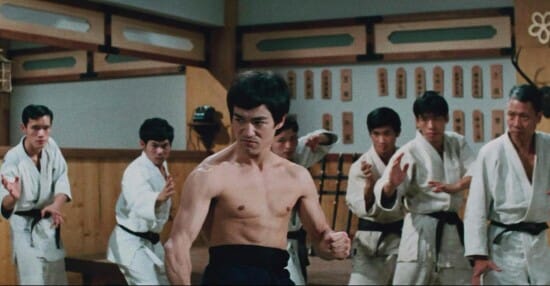

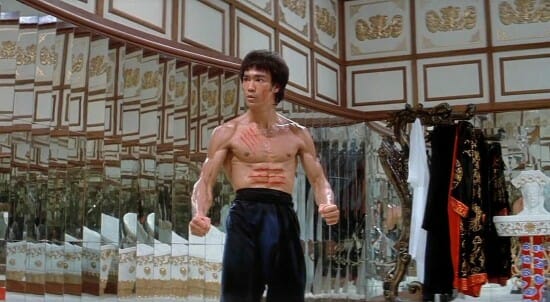

31. Fist of Fury, AKA The Chinese ConnectionYear: 1972

Director: Lo Wei

Bruce Lee’s second feature is a definite upgrade over the rawness of The Big Boss, sporting a bigger budget, better production and a story more important to Lee’s values. His character, Chen Zhen, becomes a Chinese folk hero when he stands up to the invading Japanese occupiers—especially in the classic scene where he breaks a sign permitting “no Chinese and no dogs” in the local park. This is the film where Bruce Lee truly arrived in a fully formed state, and if there’s a precise moment when that happens, it’s the classic dojo fight where Chen shows up at the Japanese training facility and absolutely goes to town on everyone inside. It’s iconic, like so many Bruce Lee moments. Do you know how you can tell just how iconic he is? Literally every piece of clothing he wore in a film has become a visual symbol for decades to come, whether it’s a simple white shirt, or this film’s navy blue suit, or of course the yellow tracksuit from The Game of Death. That’s how you know the guy is a legend. —Jim Vorel

30. Mad Monkey Kung FuYear: 1979

Director: Lau Kar-leung

Another Lau Kar-leung classic for the Shaw Brothers, Mad Monkey Kung Fu is just an inherently likable film that deftly balances feats of athleticism with broad humor. Hsiao Ho, a martial artist who does not get the recognition that he deserves, stars as a young street urchin and thief who is taken in by a street entertainer who performs alongside a trained monkey. He learns kung fu from his new teacher, and combines it with the monkey’s movements in some great training sequences. Eventually, he must use his new style of monkey kung fu to seek out a local brothel owner who is holding a young woman hostage. Hsiao Ho is wonderfully expressive in the role, and his acrobatics in particular are top-notch. He plays the part of the long-suffering, then overconfident, then humbled student perfectly. —Jim Vorel

29. The Street FighterYear: 1974

Director: Shigehiro Ozawa

Trivia blurb: The Street Fighter was the first film to ever receive an X-rating in the U.S. strictly for violence—a full 16 minutes had to be cut out to get an R-rating. Damn! This is the film that made a star of Sonny Chiba, who you will again recognize as the wizened sword-maker Hattori Hanzo in Kill Bill. He plays a truly unique protagonist in this film, an anti-hero who is far more “anti” than hero, most of the time. A hired killer, his character, Terry Tsurugi, has pretty much nothing that one would call a “moral code,” but the audience is moved into his favor when the villains who are trying to employ him instead decide to have him rubbed out. Truth be told, Chiba isn’t the most compelling actor in the world here, but man does he just have the look. The rage and intensity in his face goes a long way, and they got mileage out of it for multiple sequels. You can’t deny that the film is a classic. —Jim Vorel

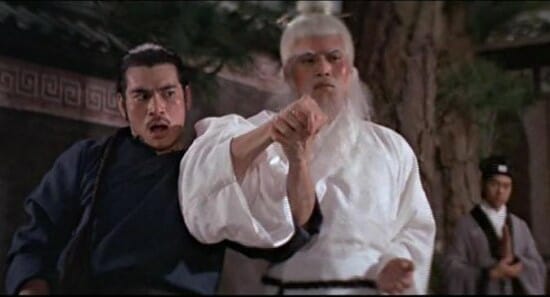

28. Magnificent ButcherYear: 1979

Director: Yuen Woo-ping

Magnificent Butcher has the slapstick and bawdy humor that one usually expects from a Sammo Hung star vehicle, but it also knows how to be deadly serious at the same time, which makes it rather unique. Hung stars as a literal butcher who has learned the ways of kung fu from folk hero Wong Fei-hung, played here by the truly magnificent Kwan Tak-hing, who was 74 at the time but puts on an incredible physical performance. The calligraphy scene in particular is legendary—a rival master comes in to challenge Wong Fei-hung, who defends himself with skill and humor while simultaneously completing a piece of calligraphy It’s in an awe-inspiring display. Butcher Wing, meanwhile, reunites with his long-lost brother and must help him rescue his kidnapped wife. The film may feature Sammo Hung’s best overall one-on-one fight scene against Lee Hoi San, really showcasing the portly performer’s acrobatics. Sammo Hung really was one-of-a-kind. —Jim Vorel

27. Warriors TwoYear: 1978

Director: Sammo Hung

Wing chun is a very influential style of martial arts when it comes to film, but it might be surprising for martial arts fans to know that true, traditional wing chun is actually quite rare on screen. Warriors Two, a modest, straightforward story of a young man training in martial arts to protect a town, is one of those few films well-regarded as featuring quite a lot of authentic wing chun, in the style which master Ip Man would have taught to a young Bruce Lee. It’s a small-scale film featuring director Sammo Hung in a supporting role, but the stars of the show are Casanova Wong as the hero and especially his master, Bryan Leung. Leung, who has appeared in numerous kung fu roles and continues to perform to this day, is affectionately known to fans as “Beardy,” but this happens to be one of the rare roles where he’s quite beardless. —Jim Vorel

26. Rumble in the BronxYear: 1995

Director: Stanley Tong

Here’s a weird factoid: Jackie Chan was 41 years old in 1995, when Rumble in the Bronx succeeded in making him an American film star. He’d already been a star in China for more than a decade, but can you think of any other martial artists who turn into a big deal for the first time after their 40th birthdays? The irrepressibly youthful Chan plays a Hong Kong cop who comes to New York for a wedding and gets sucked into a criminal underworld. It wasn’t Chan’s first American film, but it was the one that finally synthesized the trademark Chan dynamic: Fast pace, lots of physical comedy and death-defying stunt work. Don’t look for compelling acting here, because Rumble in the Bronx is as cheesy as they come. Do look for classic stunts, like Chan leaping off a building and onto a fire escape with no wires or nets. Or the epic fight in the villain’s headquarters and its hilarious use of props, especially refrigerators. —Jim Vorel

25. Wheels on MealsYear: 1984

Director: Sammo Hung

Wheels on Meals is a silly, silly movie, but damn, is the action amazing. As far as trios go, it’s harder to get better than Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao and Sammo Hung, although Hung’s role in this one is minimal. Rather, it all comes down to some incredible fight scenes featuring Chan and Benny “The Jet” Urquidez, a real-life American kickboxing champion who makes the perfect dance partner for Chan in several high-octane brawls. Their final confrontation isn’t just a great scene, it might be the best one-on-one fight scene of Chan’s career, and Benny The Jet is just as good as Chan. In fact, it’s The Jet who pulls off one of the coolest fight scene feats I’ve ever seen, the supposedly unintentional (and unfaked) “candle kick,” where a missed spin kick generates such force that it blows out all of the lit candles on a candelabra several feet away. You really have to see it to believe it. Oh, and there’s also a story about a kidnapped girl, but the kicks are far more interesting. —Jim Vorel

24. The GrandmasterYear: 2013

Director: Kar Wai Wong

Kar Wai Wong will indefatigably make anything elegant, and so it’s a given that The Grandmaster is a gorgeously paced historical epic told in patient piecemeal. A loose chronicle of the nascent legend of Yip Man, the film skirts the line between noir-ish tragedy and chiaroscuro thriller, rarely leaving room to discern the difference. From an opening set-piece that will leave you wondering why any other director since would ever bother capturing rain droplets in slo-motion, to one masterfully orchestrated balsa-wood-tower of martial arts prowess after another, there is little left to say about Wong’s directing other than the cliché: this is balletic action filmmaking—heartfelt and beautiful but never so far removed from the brutality of the action at hand that it romanticizes the pummeling of so many hapless foes. There are penalties to these punches and consequences to these kicks—there should be little doubt that The Grandmaster is not just a masterpiece of its genre but one of Kar Wai Wong’s best. That Netflix is only streaming the dumbed-down American version shouldn’t keep you from enjoying what brilliance is on display, but by all means, seek out the Chinese original. —Dom Sinacola

23. Martial ClubYear: 1981

Director: Lau Kar-leung