Nier: Automata is a Brilliant Takedown of Drone Warfare and the Escalation of Conflict

Warning: This review contains minor spoilers. Nier: Automata is a sassy game, and it would not do it justice to talk about it without explaining how it plays with expectations.

The sequel to 2010’s Nier, itself a spin-off of the Dynasty-Warriors like Drakengard series, Nier: Automata updates the medieval setting of the first game to the distant future, this time taking place after an alien invasion has supposedly forced humanity to the moon, and following humanity’s supposed struggle to take back the Earth using android fighters. Platinum Games takes over from previous developer Cavia, and the story, though taking place in the same world, is removed enough from the first to stand on its own. The eclectic hack-and-slash/bullet hell hybrid combat from the first game makes a return, though this time honed by Platinum’s master hand to create something like a lighter version of their excellent cyborg ninja game Metal Gear Rising. It’s less deep than the usual Platinum game, but bolstered by the customization and wider variety of tactics offered by the RPG and bullet hell framework. And given the two games’ similar subject matter—cyborgs, autonomous soldiers and androids—it serves as a strong complement to the game’s powerful, subversive narrative ambitions.

The setup of humans fighting ghosts from the first Nier has been replaced with a more sci-fi angle of super robots and interstellar combat, but the wider themes of separation between ruling class and pawns that presented themselves in the climax of the first game remain present. In this alien vs human conflict, both sides do not fight directly, but instead by using remote soldiers: highly-advanced, self-aware but small-in-number androids for the humans, and more rudimentary but numerically overwhelming machines for the invaders. As the game begins, players follow android fighter 2B and android intel guy 9S as they seek to reclaim Earth from the machines, who, as their name implies, the androids believe to be incapable of thought or emotion.

Soon enough, however, the player learns the uncomfortable truth to this world. In Nier: Automata, humanity is dead, and their weapons have survived them. This is not to say that the majority of the weapons are all immediately aware of this, however. As 2B and 9S’s story begins, they arrive on a relatively peaceful Earth, where large swaths of their machine enemies seem uninterested in them, almost as if they’ve joined the nearby deer and boars as part of some hybrid biological and mechanical ecology. As they walk past them, 9S comments on how strange it is that the machines don’t attack on sight. However, as they move on, they do eventually encounter hostile machines, and within the first couple hours of their mission, they find out why. Like the androids, the machines themselves face a similar crisis. In Nier: Automata, the alien invaders are dead, and their weapons have survived them.

Here, 2B and 9S face the true hands behind the machines that have been attacking them, human-like machines named Adam and Eve, who due to their design inspiration, are functionally no different from the androids, as they both resemble humanity. Adam and Eve reveal that, like Skynet, the machines have become self-aware, and they have killed the alien invaders that created them. They explain that because the aliens were, at least in their eyes, a static society, they deserved to die. According to Adam, due to the machines’ capability to exponentially escalate their growth, these two in particular having come far enough to be able to choose and take on human form, they felt it necessary to wipe out and take the place of their creators, seeing themselves as a superior race. They’ve since been building a cloud-computing style network of machines, those under their control being hostile. This also explains the peaceful machines—without their alien masters, those not connected to Adam and Eve’s network are free to live as they choose.

Essentially, Nier’s greatest trick is that its HG Wells alien invasion framework is a red herring. Instead, rather than being a war story, this is a post-apocalypse story about a group of masterless anthropomorphized weapons trying to make sense of their orders to fight in a world where the act of war has surpassed its original reasons for existing. The war and its weapons have escalated to the point where intelligent biological life is extinct. Only the weapons remain, and the weapons know little outside of combat. Essentially, by creating armies of drones, biological life has made itself irrelevant.

As the game progresses, 9S and 2B eventually learn that their situation is not as different from the machines as they originally suspected. Though they don’t realize humanity is dead at first, they come to realize their plight at about the halfway point of the game, as well as learn that along with having lost their creators, their physical and mental makeup is also more similar to that of the machines than they would like. Both being a kind of robot, it was apparent to me as a player that “android” and “machine” were already a razor’s edge away from each other as is. The more time the duo spend continuing their journey, the more they realize the distinction between the two factions they’ve relied on to give them meaning their entire life has been entirely arbitrary. An android shouting “God damned machines!” as it slays other mechanical lifeforms cannot escape being hypocritical.

None of this story exists in isolation from Platinum’s hand. Just as director Yoko Taro has crafted a mature story about the dangerous escalation of warfare when weapons such as drones take center stage over people, Platinum demonstrates this with its own Gurren Lagann style expertise at designing flashy and constantly escalating fight encounters. For instance, the first level of the game sees 2B flying through the air in a Raiden style shoot-em-up, taking out enemy fighter jets as she approaches the surface of an enemy factory. There she must fight a large industrial supply-line buzzsaw arm as a mini-boss, before infiltrating further into the factory as she slashes and shoots through hundreds of normal enemies. At the end of the factory, Platinum plays its hand completely, revealing that the entire level the player just ran through is sentient, and has been the final boss of the prologue this whole time. The factory itself rises Godzilla style out of the sea as an enemy mech, and 2B must now fight the level she just completed with just her sword. As the fight progresses, though, her escalation of weaponry also upgrades from sword to jet to Gundam style mecha, to hacking off the enemy’s own fist and using it to whack it in the face, to detonating herself in a Predator-like nuclear explosion to finish it off.

It’s an extremely anime fight scene cribbed from dozens of different media sources, but despite this, it should not be written off as “dumb” simply due to its pulp influences. Rather, it uses the skills in building constantly evolving fights that Platinum has developed with scenes such as Bayonetta vs Jubileus or Raiden vs Metal Gear Ray to neatly demonstrate how the events of the story were able to take place. In inventing drones to do their combat for them, the weapon-level of the human and aliens’ war kept escalating higher and higher until the forces supposedly leading the fighting became irrelevant, and the proxy war had taken the spotlight as a self-feeding ouroboros. It’s mutually assured destruction, but with R2-D2 and half-naked anime girls, and no other developer could have handled it as well.

This is not to say that Nier’s society of weapons are responsible for their existence, however. Though the androids have replaced humanity and the machines have replaced the aliens, they are both still sentient peoples, and are more confused by their origin than evil due to it. When 2B and 9S arrive on Earth, they find that many of the machines not on Adam and Eve’s network have built societies based on humanity’s old world. There’s a kingdom in the forest, and a small pacifist trade village whose chief exports are fuel filters and Nietzsche quotes. According to an unlockable text-log, other unseen machine settlements have tried similar approaches, building all kinds of governments based on humanity. However, whether a dictatorship, monarchy or democracy, all of these governments eventually seem to fail. Some kicked up again after their failures, but the machines simply repeated the same failures again and let their societies crumble a second time, which the log contrasts with humanity’s ability to learn from its mistakes. Essentially, the drones of Nier wish to be something more than instruments of conflict, but as they are weapons, they are bad at aping humanity.

The androids, however, are maybe the closest thing to humans left in this mechanical ecology. With their bodies based on their human creators, they look like humans. They bleed like them. They talk like them, move like them. And as is revealed as they interact with each other more, they desire like them—both heterosexually and homosexually. It seems, deep down, that they feel emotions like humans did, or at least as close as a weapon can get to replicating it. They are humanity’s legacy, and the closest thing to humanity surviving would be for them to take on their creator’s mantle and start their own society on Earth.

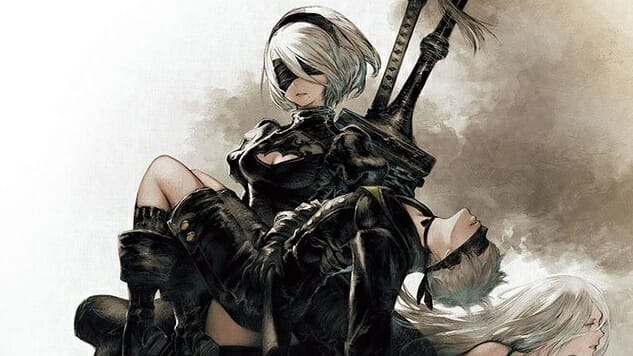

However, they can’t escape the purpose for which they were created. Seeing themselves as humanity’s servants as opposed to humanity’s children, they choose to block out their emotions. They cover their eyes, creating walls between Earth—their birthright—and themselves. Even the costumes that could be easily dismissed as simple fanservice serve a narrative purpose here, as the androids refuse to decorate themselves with colors or patterns, and instead dress in the style of butlers and maids, their austere black-and-white dressage complementing their desire to be seen as things more than people.

To a degree, there’s a reason for this puritanical lifestyle. As with the machines that tried and failed to recreate human governments, weapons—android or not—emulating people isn’t always guaranteed to be successful, and in worst case scenarios, can turn dangerous. For instance, some of the machines wear makeup, and while those who do so in the pacifist village have no difficulty living in peace for the most part, there’s also the case of the machine boss Simone, whose obsession with decorating herself lead her to cannibalize parts from other machines and eventually go insane. Again, weapons are bad at being people, and a community based on them is bound to fail.

With all this in mind, Nier: Automata could be read as a cynical game, about a society where war is pointless, and yet continues to be fought because that is all Earth’s new conflict-born inhabitants know. Where humanity is dead, and its last remaining legacy is so terrified to take its place that it only furthers both of their extinctions. Where factions are arbitrary and intelligent life—mechanical or not—is almost dead. Where the scale of war keeps climbing higher and higher, and makes Earth more and more inhospitable to life with each new escalation. Where every victory is pyrrhic, because all the machines and androids have left are each other and their dwindling numbers, each blow against the other leading closer to an extinct planet. And yet, where all attempts to change this cycle are doomed to fail, as with Simone and the repetitively incompetent machine governments. It’s a world where, maybe, Earth’s fate of going extinct at the hands of its own weapons can’t be avoided, even when a peaceful resolution between its innately violent inhabitants seems right around the corner.

To a degree, this cynical read is true. Director Yoko Taro’s work has always sought to complicate the violence that is often read as a non-issue in games, and his protagonists are typically not good people. On stage during Square Enix’s press conference at E3 2015, Taro explained that “That depiction of violence in games is what I don’t think is right. I think it’s more realistic to have a character defeat or kill an opponent and then sit and have to struggle with the realization that they took someone’s life.” As such, Nier: Automata could easily be read as a warning not to let war get out of hand, not to glorify drones or the increasing scale of conflict as fun, as a supposedly heroic character from another game might when they smile undisturbed after killing someone and say, to quote one of Taro’s examples of the type of games he dislikes, “‘yeah, we beat the enemy!” This bleak viewpoint is certainly a substantial part of the game, as about three of the game’s non-joke endings focus heavily on it. However, as much as I’ve already spoken about in regards to this game, I’ve barely scratched the surface of Nier’s surprises, to the point where I feel comfortable only classifying this review as having minor spoilers in my disclaimer.

In the final twenty minutes of Nier: Automata, during its true ending, the game breaks the fourth wall and lays all its cards on the table in a way I can’t explain in detail without feeling like I’m robbing you. What has up to this point been a largely single-player experience inside a fictional world suddenly leaves the game world and takes on a multiplayer framework set in real life. It’s the most memorable ending to a game I’ve played since Naked Snake vs the Boss in Metal Gear Solid 3, and it is dominated by a single emotion: cheesy, grin-inducing, “I fight for my friends” style resolve. Here, the game directly recognizes the dangerous cycles of inescapable violence and doomed peace it has philosophized on through more subtle theming for about 50 hours, and suggests two solutions: the leaning on experienced perspectives other than one’s own to fill knowledge gaps, and at the same time, the willingness to make real, painful sacrifices to share one’s own unique perspectives to help others fill their own knowledge gaps. Here, the game’s characters and the people playing them are not islands, and where there were no solutions before, a difficult but earned and mutual exchange of care and information among the desperate allows for, if not a new path, at least a second chance.

Nier: Automata is a mature, sophisticated game that avoids the JRPG trap of the narrative, the themes and the play being separate entities. Platinum and Yoko Taro are an expert pair here, harmoniously bringing together dozens of eclectic sources from philosophy to anime to history to real-life war to silly, over-the-top fight sequences into one cohesive whole where not a single part feels unnecessary, and all contribute to the larger message. It is a timely story about our priorities as a society and our continued relevance in an increasingly automated world, told in a clever way that makes meaning out of about four different genres worth of mechanics and yet could still be called elegant. It’s a sharp commentary that could only be done through games, and for now, it is easily the magnum opus of either of its authors.

Nier: Automata was developed by Platinum Games and published by Square-Enix. Our review is based on the PlayStation 4 version. It is also available for PC.

Michelle Ehrhardt is a critic and journalist living in New York City. She has written about games for Kill Screen, Out, Bullet Points and the Atlantic. You can find her on twitter at @chelleehrhardt.