The Holocaust, Art, Chicago & Sickness: A 3,500-Word Interview with My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Mastermind Emil Ferris

"All I wanted to be as a child (and still want to be) is a monster."

Comics Features Emil Ferris

The first volume of Emil Ferris’ debut comic, My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, was scheduled for release last October, timed to coincide with Halloween. But the company that owned the ship carrying the printed books went bankrupt, leaving its cargo in a terrible limbo that delayed the book until this month. In some ways, the hiccup was fitting. Ferris’ book has been anticipated for much longer and undergone multiple iterations. It’s the sort of achievement that requires a certain sense of mission to complete. But it’s here now courtesy publisher Fantagraphics, and it is well worth the wait.

Oversized with a paper binding, My Favorite Thing Is Monsters feels heftier than if it had a board cover, yet ephemeral at the same time. The story draws on EC Comics, Holocaust literature, detective fiction, monster movies, children’s literature à la Harriet the Spy and more, weaving a complex tapestry through the 1960s that surprisingly parallels our current era. Are its monsters a metaphor or a reality? And are the people in it who look like monsters the ones we need to fear? Ferris doesn’t supply simple answers. Instead, her work fuses the style and atmosphere of noir godfather Raymond Chandler with the passionate moral intensity found beating beneath a good episode of Tales from the Crypt. She agreed to unpack some of her book’s themes in an email interview that lasted through multiple back and forths.![]()

Paste: I’ve read that you don’t like to get out much. Is Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window an influence on My Favorite Thing in Monsters?

Emil Ferris: That’s interesting. From the perspective of a disabled recluse, I definitely identify with the voyeuristic approach inherent to the James Stewart character. Not a parallel I’d ever considered but very apt.

Paste: How much time do you spend watching your own neighbors and trying to figure out their stories?

Ferris: While creating the book, I had a studio a while back that was a dozen yards from an el platform. Having no television, I’d regularly take my work breaks at the window and while monitoring the passengers embarking/disembarking, I assigned names and stories to them based on their mien, carriage and general demeanor. There was Colonel Archibald Shlump, Mr. Fast Pants, Circus Sue and Dino the Behemoth, Ronnie Rabblerouser and many, many more.

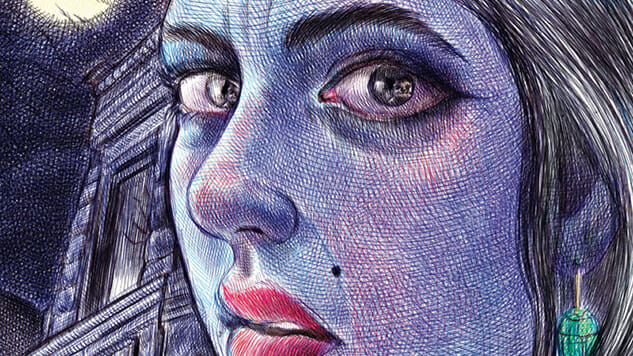

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: Did you base any characters in the book on folks you saw from your window by the el?

Ferris: Apologies! I was so snarky to mention those silly reductive names for the characters I saw. I really did know that there was much more to them than the goofy names I gave them. No, not really based on the el travellers, per se, in terms of characters. This is the part where I’m supposed to say that my characters are not based on anyone in real life…yeah. (Heh!) I read a quote to the effect that we are always writing about ourselves no matter what we’re doing. That may be so.

Paste: What is that amazing textile in the background of your press photo?

Ferris: It’s a vintage silk embroidery made by the Uzbek Suzani from Samarkand. I have a profound interest in embroidery as I have female ancestors on both sides who embroidered their way through great trials. On my mother’s side was a Sephardic Jewish ancestor who, in flight from the Inquisition, created a Colcha (still held by a family member) in the hull of a ship traveling from Spain to the New World (Mexico City/Taos, New Mexico). On my father’s side was my 18-year-old Lebanese grandmother who created vast images in thick lace in order to endure her unhappy and non-voluntary arranged marriage to my 56-year-old grandfather. Sewing a drowning self to the intimate details of a thing in order to be bound to the buoyant greater whole seems to be a familial bent. I think working on this book represented my salvation as an artist and a person.

Emil Ferris Press Photo Courtesy Fantagraphics

Paste: Can you talk to me about why you’re only making your debut as a comics artist now? It sounds like it might have something to do with it being your “salvation as an artist and a person.”

Ferris: I’m in my 50s, and I’ve been making stories with pictures all my life, but this is the first one I’ve shown anyone. Yes, doing a work, telling a story very much represents a way to save my own life and on so many levels. Not sure if I told you about being disabled (profoundly bad scoliosis), and because I couldn’t run I discovered the value of telling stories (ghost/horror stories) in order to have any kids around me during recess. Essentially making this book was the way a very isolated/reclusive person sought to engage with the world and offer something of value.

Paste: So what gave you the kick in the pants to start drawing this book?

Ferris: As a seriously disabled person who had tried again and again to enter the job market and was rebuffed regularly, I knew I would have to create my own way to survive. (While applying for an ad agency job, I was asked—in the event of a fire—if I thought I could carry a computer down a half-dozen flights of stairs and this “saving the life of a computer” was actually implicitly posited as a mandatory ability for an employee!)

So I knew I needed to create something that satisfied my desire to have a positive impact and at the same time might be appealing to an audience. I had studied under Anne Elizabeth Moore, who is a solid believer in the power of comics as a catalyst for social change, so it seemed like a no-brainer. The response I got to the first 24 pages of the book—I was honored by being made a Toby Devan Lewis Emerging Artist Fellow—seemed to confirm to me that this was the correct way to go.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: Talk to me more about your disability. Scoliosis plus West Nile Virus, right?

Ferris: I was born with fairly serious scoliosis and I did not walk at all until I was about two-and-a-half years old. At 10, after years of extreme pain (my crooked spine made my legs different lengths, breathing difficult and it was literally very close to running into my heart) I had corrective surgery that required my being in a body cast for nine months. When I gave birth to my daughter my spine was further damaged.

As a consequence of the birth I had some spina bifida occulta and that was like a restaurant “We’re Open” sign to West Nile virus. So that when I got bitten, the virus hunkered down to dine on my spine. The result was not only encephalitis, but also meningitis and, of course, lower body paralysis and partial paralysis of my right hand. I have recovered from some of it, but not all of it.

Paste: Did you make comics growing up and, if so, did you use a lined-paper notebook like the one this book mimics?

Ferris: I did. I began to suspect that I could communicate this way when my classmates in grammar school and high school, kids who did not like to read, would hijack and pass around my notebooks/sketchbooks for long periods of consideration.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: Did you choose the lined-paper background to evoke childhood?

Ferris: Exactly so! But also to offer a structure against which I could rebel. I received a book as a kid from my aunt (a fabulous New Mexican embroider by the name of Ann Spiess Mills). The book was called My Name is Lion. It was about a Navajo boy who is given a lined notebook and says in response that he is going to defy the lines and draw against them. I loved that when I was a kid, and [My Favorite Thing Is Monsters protagonist] Karen loved it, too.

Paste: Did you draw in those lines? Use a computer? Surely you didn’t work on actual notebook paper?

Ferris: Every drawing is hand drawn with ballpoint pen and the text is made with felt tip pens. This is appropriate to the year which is meant to be 1968. Very quickly I realized that lines would make corrections nigh on impossible, so I created a drawing layer which was set over a notebook layer.

Paste: What brand of ballpoints/felt tips?

Ferris: Bic pens for images. Paper Mate Flair pens for text.

Paste: How did you develop your cross-hatching-heavy style? And why did you stick with it for this (extremely long) book? Doesn’t it take forever?

Ferris: Yes, Hillary. It really does make a case for me being a lunatic. But I love the sculptural possibilities. I love the way each line on its own means something and is loaded with its own expression—full and unique—but the confluence of the lines en masse brings out an even more poignant vision and, hopefully, a truth. I thought about this while viewing the recent Women’s March.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: So is it almost a devotional practice? Like the way Lynda Barry encourages people just to keep the pen/pencil moving?

Ferris: I think I’m a sculptor at heart. I define space, find form, using these swaths of arching lines. That’s the joy of it. Carving out form from the flat page. Creating textures and shadows that simultaneously harbor dark, faintly seen things and expose other things to scrutiny. The technique has a parallel—not just within the historic context of horror comics—but within the very nature of monsters as beings who must remain occult (hidden) and disguised, and yet also fluidly transformative.

Paste: Why veer away from a more traditional panel structure and opt for a more free-form, full-page composition in this book?

Ferris: When I sat down to figure out how to make this story, I knew there were things that I required as an artist/author and things I felt my readers required. It was a matter of freedom and generosity. I needed freedom and I wanted to give the reader the most expanded, articulated and visually dense experience I possibly could. So many things that wouldn’t fit into boxes. Also I sat down to do this and this was the only way I could do it. I knew what the canon was, but it was somewhat hard for me to be that constrained.

So, in a weird act of “faith” or something, I imagined I was in constant communication with my future readers. I was opening worlds that I saw in my head for them and hoping that the visions would catch hold, engage and communicate the story, even though (and maybe even because) it was getting created very much against the lines.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: What’s your favorite medium to work in (i.e., pencils vs. oil vs. whatever; not so much comics vs. animation)?

Ferris: I love oil and in some ways that’s a part of my process with the book. The glazing of a painting in successive applications creates evocative contours, darkness loaded with barely perceptible mysterious images. I can spend great long hours decoding the secrets and hidden symbols embedded in Renaissance oil paintings. I knew Karen felt the same way. I wanted her book to express that love of the occult and arcane things that are all around us.

Paste: Some of my favorite parts of the book are the visits to the Art Institute of Chicago. What are your favorite works in its collection?

Ferris: One that was meant to be in the book but that I did not get permission to use was called, “The Village of the Mermaids” by surrealist Paul Delvaux. So many hidden treats! The other collection that absolutely enticed and engaged me as a kid was also my first lesson in sequential art. It was a wonderfully gory devotional series by Giovanni di Paolo. It traces the imprisonment and execution of St. John the Baptist in stages. Of course I was entranced by the painting of his headless body spraying a mute arc of blood into the pristine city of his martyrdom. (I’ve included those here for your ghoulish viewing pleasure.)

There is a recent acquisition by one of my fave artists, Otto Dix, that I’m scrounging around to find a copy of so that I can show you. It absolutely evokes the whole experience of living in Nazi Germany and does so via a landscape with not a single human form in sight. It is brilliant.

Saint John the Baptist Paintings by Giovanni di Paolo

Paste: Did you grow up in Chicago (and visiting the Art Institute)?

Ferris: Yes, my parents met there as art students and got together and made me and then decided they ought to marry. In a way—considering that my parents weren’t exactly religious or church-attenders—the Art Institute was the high church of their faith. The Louvre was Vatican City for two people whose religion was art, but the Art Institute was definitely their Notre Dame.

Paste: Do you feel like Chicago’s having a cultural moment right now (Kerry James Marshall, Obama, Chance the Rapper, way more)?

Ferris: Absolutely. Chicago has always been an idiosyncratic wonder of a city. Established by a person of color, Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, we know that in its history Chicago has often been the seat of commerce for the entire country, but it’s also been the conscience and the catalyst of the nation. This is an extremely hard-working city, so it is no wonder that artists—such as those you mention—who are capable of full-tilt shlepping distinguish themselves.

Chicago always amazes. Being a Chicagoan is like being loved deeply and loyally by your broke-nosed uncle whose business dealings you must never examine too carefully. I love this city like no other.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: Not only is this book set in the 1960s, but it also feels very ‘60s, like the underground comics of the era. And at the same time not (it’s neither sexist nor doped out!). Discuss?

Ferris: The sexism of the 1960s (and the sexism of its cultural producers within the world of comics) really bummed me out when I was a kid. Inherent in the sexism I sensed this implicitly held belief that women had very little of value to contribute, other than their bodies as objects of male desire or (in Karen’s eyes) as voluptuous sacrifices to monsters.

I knew there was so much more to this that as a child I couldn’t quite grasp yet. Book 2 deals with that much more. It also explores Karen’s confusion around these ardently objectifying portrayals of female beauty as beheld by a feminist-leaning child who knows herself to be lesbian.

Paste: You grew up reading some of those underground comics, right? Which ones? Do you think there are any comics artists that are particularly influential on your work or is that more a role for fine art?

Ferris: I had very liberal parents—exceptionally so, I think. I saw [Ingmar Bergman’s] The Virgin Spring at seven. So I read The Fabulous Furry Freak Bros, Fritz the Cat and other things. I loved the illustrative chops of Robert Crumb and his contemporaries, but I was often dismayed by the spirit of misogyny in the work. I think it was honest, though, an honest telling of what it felt like to be a man in the 1960s, a person with foibles, insecurities, libido and anxieties, and out of regard for that honesty it was possible to see the misogyny in context. It was most understandable when it was confessional, although I could see how the objectification of women’s bodies and the minimization of their personhood was relatively standard fare in comics. I think everyone—men, women, boys, girls—were subtracted from as a result of that misguided social arithmetic.

I remember being utterly engaged with Burne Hogarth’s drawings of Tarzan, Edward Gorey and Aubrey Beardsley (who enjoyed renewed attention during the late ‘60s) all things EC and Mad Magazine. Of course I spent cumulative years of my childhood standing in front of the work of the great masters of etching and lithography. Among them were artists whose work leant, in varying degrees, towards caricature, such as Goya, Dürer, Rembrandt, Daumier and Grosz.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

Paste: The print-makers you mention tend to focus on war and the terrible things we humans do to one another. Do you think the role of art is to help lead us out of that darkness? To expose the terrors of the world?

Ferris: Painter Susanna Coffey said “Beauty is the thing that allows us to wrap our minds around even the worst.” I would add that the generosity of our artists is to robe our most difficult truths in palatable beauty. The catharsis and empathy possible within fiction are potentially life-saving on every level. Often while I was making the book I thought about the role of storytelling in Anka Silverberg’s endeavor to rescue children from a concentration camp and get them to the freedom beyond Hitler’s Germany.

In My Favorite Thing is Monsters, Anka uses myths and stories to equip these children to understand the evil around them and to survive it. I think that humanist/benevolent storytelling is such a willing participant in the effort to rescue the human soul. (It can carry that computer to safety down innumerable flights of stairs!) And that is exactly what we as creative people—as artists, as writers, as thinkers, as whole humans, are able to do when we wish to.

Paste: Part of what makes your work feel like the ‘60s to me is its focus on World War II and the aftermath. It has a more immediate connection to that war and the Holocaust that’s palpable, as opposed to most work made now about that era. Can you talk to me about your own family’s engagement with World War II?

Ferris: To my knowledge, I have two uncles who served in the US military and in some capacity fought in World War II. I was not close with either of them and noted how damaged they both were, ostensibly from their war experience, although I’m not certain of it. No, the real understanding that I personally gained of the war was the result of living in the Chicago neighborhood of Rogers Park, wherein a great number of Holocaust survivors lived. I actively pursued their stories and was fortunate when a few of them opened up to me. I then made it a course of study to research all that I could about the time they’d lived through.

“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” Etching by Francisco Goya

Paste: We haven’t talked about monsters too much. Is that Goya print (“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters”) an important touchstone for you? Do monsters just work as a complex metaphor?

Ferris: Exactly! Yes! Goya was very important to me as a child. This was before I even knew that my family had a connection to the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition or that my grandmother was essentially a Crypto-Jew. I was awed by his work and understood that it was his way to speak truth to power.

I felt a profound empathy in regards to what I call the “personal monster dilemmas” of each creature within the monster pantheon, but this was especially true regarding the Wolf Man. The 1941 movie The Wolf Man was written by Curt Siodmak. Siodmak was a German Jew who left Europe. It’s important to note the use of the pentagram in the movie. The pentagram appears in Larry Talbot’s hand as an evocation of the Star of David. Of course Siodmak had experienced the forcible “branding” and registry of Jews under Hitler. The implication is clearly that the mark indicates an “accursedness” that brings about suffering and even death.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters Interior Art by Emil Ferris

It is extremely interesting to note that the December 9, 1941 opening of the movie was bracketed by two other significant dates. December 8, the first killing operations at Chelmno in occupied Poland; and December, when Nazi Germany declared war on the United States. I’d really been moved by the plight of the Wolf Man and carried that throughout my childhood, but while researching the book I was amazed to discover the close association between the movie’s creator and the Holocaust.

Paste: What percentage of Karen would you say is autobiographical/based on you?

Ferris: Like the saying goes, “These things never happened, but the story is true.” In this case though, there are a great many things within My Favorite Thing is Monsters that are TRUE and DID HAPPEN. How much is me? A great deal. Karen is very much an honest part of me. All I wanted to be as a child (and still want to be) was/is a monster.