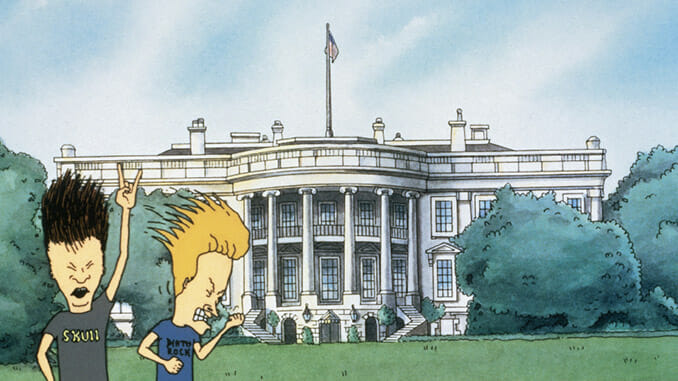

25 Years Later, Beavis and Butt-Head Do America Still Bears Witness to a Country Going Down

Images courtesy of Paramount Pictures Movies Features Beavis and Butt-Head

Twenty-five years ago, Beavis and Butt-Head Do America premiered to a then-record-breaking $20M-plus and number one at the box office in its titular country. More than that: It topped Scream’s first weekend and Jerry Maguire on its slow ascent to a melodramatic $153M worldwide, all during the height of the holiday season. The first title under MTV Films’ animation arm, Do America touted a respectable—if modest compared to even that of a small Disney operation (i.e., The Great Mouse Detective’s $14M)—budget of $12M and remained, like the six seasons of TV series preceding it, under the direction of creator Mike Judge. For the first time, our vertically symmetrical, barely literate teenagers, pituitary glands beaming and engorged, will venture from their vaguely Southwestern suburb of Highland to cross, to truly see, this big and beautiful nation. For a brief moment in time, for one winter eve, audiences in the United States felt connected to Beavis and Butt-Head—felt held, understood, truly done by them.

All Beavis and Butt-Head want, in order of priority, is to score, and then to get their TV back, the latter the reason they venture from their couch at all. It’s never really addressed whose couch it is, because Beavis and Butt-Head go largely unsupervised, their moms never around, their dads non-existent, the adults they know all for the most part ineffectual and openly hostile, and school apparently optional. The couch is also where they sleep—upright like John Merrick the Elephant Man, lest the weight of their enormous skulls suffocate them when lying down—next to one another, best friends who share physiognomy and one day, they hope, a consenting sexual partner.

In 1992, Mike Judge introduced his creations with a short in which Butt-Head murders a frog with a baseball bat. He called it “Frog Baseball.” From there, Judge has preserved an amoral purity to the pair: Voicing both, as well as most characters, Judge poises Beavis and Butt-Head as American teenage boys obsessed with archetypal American teenage boy shit, like sex puns and metal music videos and processed cheese, by default the unadulterated, unmitigated products of archetypal American teenage boy shit, raised by TV and ignored by whatever social safety net wasn’t already dismantled in the late ’90s. They live in a small town full of people who detest them; their bodies do not show evidence of balanced, home cooked meals. Any silence they fill with the white noise of their giggles, like pubescent bats stumbling into and sounding out the contours of their world. Beavis and Butt-Head was an instant sensation for MTV as it slowly shifted into shows less directly related to music, even more impressive given the barely four years between cable TV and movie premieres. Judge had conjured characters who spoke directly to real American values: Solipsism, arson, shitting, jacking off everywhere, harassing veterans, malnutrition and talking about having sex. We watched Beavis and Butt-Head watch TV. There was no greater entertainment.

Mike Judge is obviously the only man who understands Beavis and Butt-Head. In ancient-looking BTS fodder—included with the new Beavis and Butt-Head Do America 25th anniversary Blu-ray release (heh, “release”)—the film’s animation director (the first time Judge has ever had someone in that title due to the luxuries of a movie budget) says as much. (Heh, “erector.”) Studio executives repeatedly attempted to interfere, to re-cast the voices of Beavis and Butt-Head with A-list actors or to even mount a live-action production, but Judge’s workmanlike attitude toward all creative endeavors seemingly appeased them. If Beavis and Butt-Head Do America still looks intuitive and lived-in, it’s because it’s mostly hand-drawn—an anomaly we’ve all but erased from our cultural awareness—and because Judge figured out how to logically expand the show’s palette for a physically larger screen. If Bill Frizzell’s score better suits a blockbuster film, it’s because he called up Elmer Bernstein, composer for Airplane! and Ghostbusters and Spies Like Us (among many), to learn how to walk the disappearing line between parody and homage. If you’re wondering if “they” just don’t make ’em like they used to anymore, it’s because they don’t: Do America represents a studio animated film born from creative decisions made by only a very few, steered by a single, inimitable artistic (heh, “dick”) vision.

But (heh) the movie’s shallow pleasures run deep (hehe). Even the film’s title, a simple play on the Debbie Does porn series, becomes a one-note pun that drives the film’s main plot. Looking for their stolen TV, stopped from stealing a high school’s TV by mewling teacher Mr. Van Driessen (also Judge), Beavis and Butt-Head wander to a seedy motel, where a towering sign informs them that color TVs await inside each room. First they break into a room where their school Principal McVicker (also Judge) appears to be receiving a spanking from a woman in elaborate lingerie. They laugh and think this is “cool.” They leave unpunished. Next they break into another room where the conspicuously scummy Muddy (Bruce Willis, who agreed to the film only if a small crew flew to Willis’s Idaho ranch to record), a bottle of cheap whiskey already to the dome, mistakes them for hitmen he’s hired to “do” his wife. Immediately, they agree, refusing to question the arrangement, looking forward to finally scoring and having enough money to buy a new TV—“with two remotes,” Beavis reminds Butt-Head. So goes the majority of exchanges Beavis and Butt-Head have with other human beings:

Muddy: You gotta watch out cuz she’ll do you twice as fast as you do her.

Butt-Head: (wide-eyed) Whoa! …huh huh… cool.

On the way to the airport, where Muddy will drop them off so they can fly to find the person they’re supposed to do, Muddy looks to the boys as the sit in the backseat, catatonic as they tend to appear:

Muddy: Any questions?

Butt-Head: Uh…does she have big hooters?

Muddy: (grins) Haha, yeah she does …Hey, you guys are funny. Let’s drink on it, huh?

Thus begins their journey to do America: To experience it, to fuck it, to kill it. Put on a plane as if by providence, they act completely unaware of what they’re doing or what air travel is. They stare vacuously at their seatbelts; as soon as the plane takes off, Beavis screams that they’re all gonna die, and Butt-Head gets out of his seat to grope the flight attendant. They almost cause the plane to crash. They go unpunished. They meet the woman, Dallas (Demi Moore), whom they’re supposed to do, but realizing there’s more than one way to interpret a basic verb, she embroils them unwittingly in a criminal conspiracy, convincing them to get on a bus to cross the country to Washington D.C., giving her a chance to safely recover the “X-5 Unit” (a stolen biological agent) from where she’s secretly sewn it into Beavis’s shorts. They meet a kind old woman (Cloris Leachman) and continue with her and her tour group onward, avoiding the authorities, doing more and more of America.

Beavis and Butt-Head are innocents because their ignorance knows no bounds. Their egos are prelapsarian, somehow untouched by thousands of years of evolution, the perfect archangels to bear witness to a failing empire five years before 9/11 and almost a quarter century before the Capitol riots. They aren’t trying to deface national monuments or offend nuns or disregard the grandeur of the United States of America, laid out before them in all its bounty, but they are doing those things, and in all cases it’s very funny, especially because it absolutely does not matter that they do those things. In Virginia, they cause “the worst highway disaster in this nation’s history” but walk away and board the bus conveniently waiting for them, which drives around a silhouette on the side of the road crying for help over a motionless, prone body. Rancid kicks in on the soundtrack. They walk into every private corner of the White House unabated. Butt-Head hits on Chelsea Clinton; Beavis masturbates in the camper of his neighbor Tom Anderson (also Judge), eventually getting Tom arrested by the FBI, his head caved in by the butt of a gun and the aforementioned masturbated-in camper—which he was using to vacation with his wife in D.C., to see the great Capitol he’s spent his whole life defending, the mobile home he’s worked hard to buy so he can finally “do” America the right way—further destroyed by federal agents. “Cool,” Butt-Head says, watching all the militarized gear lined up and ready to brutalize some citizens. Yes, it is cool that Tom Anderson, this dedicated war veteran, is not only rewarded for his patriotism with violence and oppression, but punished for the chaos Beavis and Butt-Head wantonly embrace. God knows how many homes or businesses were wiped (heh) out when Butt-Head unintentionally opened the Hoover Dam, how many working class lives were subsumed under his need to push a button that he thought had something to do with cranking one out. And instead of taking responsibility for the devastation wrought in their wake, Beavis and Butt-Head get to meet Bill Clinton, who makes them honorary ATF agents. “Heh …We’re in the Bureau of beer and fire and cigarettes, heh,” Beavis clarifies. Bill chuckles.

Accordingly, worldbuilding—the bread and butter of TV-to-movie feasts—doesn’t matter. “My first name is Butt,” Butt-Head tells a stranger, in much the same way Solo explains how Han (Alden Ehrenreich) got his last name. This information exists for itself, not as part of a broader constellation of mythologies, but only because it brings light to this dark world that Butt-Head goes by his full name, and that also his first and last names are hyphenated. It could make sense that a teenage boy who lives with his other functionally orphaned best friend goes by his hyphenated first and last names because he knows nothing else, because this child named Butt had no one to tell him he could be called anything else, but the details surrounding Butt-Head’s name have nothing to do (heh) with scoring or getting TV back.

Eventually, lost in the middle of the desert, on the precipice of death, Beavis and Butt-Head do meet their fathers, the elder Head voiced (under a pseudonym) by David Letterman. Though they share a meal, and a few cool stories about boning women in Beavis and Butt-Head’s hometown are revealed, nothing comes of it besides an impressive fart explosion. The dads leave before Beavis and Butt-Head wake up, abandoning them once again. None of it really matters anyway, and the two survive the wasteland, another generation just like the last, living to do America for yet another day.

Twenty-five years later, wandering into the White House or through the airport carries much weightier historical precedence than it did—fear and anxiety fully subsumed into the fabric of our quotidians—but not much else has changed. Masculine, hormonal wads still roam this land, defining it, conquering it, not even realizing what they’re getting away with. There is nothing more American than blindly storming into something, then fucking it up, then never taking responsibility for any of it. Beavis and Butt-Head Do America chronicles that endless sowing followed by that utter lack of reaping. “I poop too much…then I get tired,” Beavis tells the old woman. This is the most he understands about consequences. And this is what happens sometimes when you’re doing America. Not to all men, just some. More than you’d think, though. It’s OK. It doesn’t matter.

Dom Sinacola is a Portland-based writer and editor. You can follow him on Twitter.