As the Great Depression hit Hollywood and beyond, the booming silent era of the 1920s morphed in both sensory technology and theme, generating the best movies of the 1930s. Talkies, even some in Technicolor, navigated responses to hardship that reveled in high escapism, genre symbolism and the strict idealism of Soviet socialist realism. The 1930s were a time of screwballs, musicals, Universal Monsters and the looming conservative crackdown of the Hays Code.

Some movies from the 1930s remain household names today, classics for nearly a century like The Wizard of Oz and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Some remain the most influential movies of their type, like King Kong and It Happened One Night. Others that may have fallen out of contemporary conversation require revisiting. You might be surprised how deeply the work of Jean Renoir, Charlie Chaplin, King Vidor, Yasujiro Ozu, and many more still resonate almost 100 years later.

Here are the best movies of the 1930s:

60. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)Director: Frank Capra

Similar to All The King’s Men (and not just because it’s incredibly old), this film chronicles the tale of Jefferson Smith (Jimmy Stewart). He’s the leader of a Boy Scout troop before being recruited to the Senate by a team that believes he’ll do whatever he’s told—specifically, allow the building of a dam that will make said team rich. But unlike All The King’s Men, the main character isn’t corrupted by politics, but rather defies and decries the corruption. Directed by Frank Capra, Mr. Smith has major sentimental overtones and desire for a fantastical world, as Stewart’s character displays a fortitude and integrity we wish all politicians had.—Nathan Spicer

59. The Prizefighter and the Lady (1933)Director: W. S. Van Dyke

The light romantic comedy stylings of this film are livened up by the star appearances of several celebrity prizefighters of the period. Myrna Loy plays a fashionable nightclub singer and gangster’s moll toying with the heart of Max Baer, the real life heavyweight champion. With the legendary Jack Dempsey as a referee and Baer’s real opponent Primo Carnera in the ring, it’s difficult not to play a game of “spot the celebrity” as you’re watching. In spite of the fact that at one point, Baer attempts to do some singing, this is a thoroughly entertaining, if patchy, old Hollywood movie. —Christina Newland

58. Riders of Destiny (1933)Director: Robert N. Bradbury

After the box office failure of Raoul Walsh’s major studio epic The Big Trail in 1929, a movie intended to make the young John Wayne a Western star, the budding actor dusted off his chaps and fled to smaller independent studios to hone his craft. For the next decade, until John Ford resurrected him in 1939 as a bona fide screen presence in Stagecoach, Wayne became a matinee idol in numerous entertaining though mostly forgettable B-movie oaters. Riders of Destiny, his first of many for Monogram Pictures, is notable for a number of reasons. Among them—it marked Wayne’s first performance as a singing cowboy, and the movie’s action sequences are brilliantly choreographed by the legendary stuntman Yakima Canutt, who also plays one of the villain’s henchmen in the picture. As with many of these so-called Poverty Row Westerns of the 1930s, Riders of Destiny is a brisk narrative and high on sensational plot twists. Villains are dastardly, in this case a corrupt savage capitalist played by Forrest Taylor, who intends to steal all of the water from surrounding ranchers, charging them an exorbitant fee for its use. And our hero is stalwart and true, here played by Wayne. What makes this singing cowboy more interesting than all of the yodelers who would appear on screen afterward is a simmering violence and darkness within him. None of it is laid on too thick; Wayne’s character is ultimately true blue and on the side of goodness. But neither Gene Autry nor Roy Rogers would ever sing about the “blood a-runnin’” just before showdown. A minor though significant entry in Wayne’s filmography. —Derek Hill

57. Iron Man (1931)Director: Tod Browning

Tod Browning—a director of the 1930s far more legendary for his monster movie creations (Dracula, Freaks)—turned his attention to the boxing ring in this early sound film. Starring two very famous actors of the era—Lew Ayres and Jean Harlow—this film reveals the pitfalls of the successful fighter, grown arrogant and idle with his wealth. While Iron Man is a fairly straightforward and par-for-the-course boxing drama, the talented cast elevates the material—Harlow was the perfect gold-digging moll, and had been a prizefighter’s squeeze in real life. —Christina Newland

56. Ninotchka (1939)Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Greta Garbo’s emotionless bureaucrat personifies the then-young Soviet machine in Ernst Lubitsch’s pre-war classic—at least until she learns to love both a man (Melvyn Douglas) and the freedom of the West while stationed in Paris. It can be a little surprising to see how early our conception of Russian Communism was fixed in popular culture—the jokes often revolve around Russians who can’t believe the mundane creature comforts of the West, which remained a fixture of Cold War anti-Russian comedy into the early 1990s. Still, Garbo is transfixing in her first comedy, backed by genuine romance in her flirtations with Douglas. —Garrett Martin

55. Kid Galahad (1937)Director: Michael Curtiz

This is fairly run-of-the-mill Warner Brothers fare of the Depression era, right down to the spinning newspaper headline montages and cigar-chomping promoters. Michael Curtiz (of Casablanca fame) directs the story of a good-looking, cornfed fighter whose career is taken on by a well-heeled manager (Edward G. Robinson) and his sympathetic girlfriend (Bette Davis), but through his wholesomeness, eventually appeals to his manager’s better nature. It may be a touch predictable, but it’s hard not to like any film starring Bette Davis, Edward G. Robinson, and Humphrey Bogart—snarling at each other in smoky rooms and chomping on cigars in rough old gyms. —Christina Newland

54. The Old Dark House (1932)Director: James Whale

Given the name, you’d be forgiven for assuming that this long-forgotten and then rediscovered James Whale classic had created the genre we colloquially refer to as “old dark house” movies, but in reality, the Frankenstein director seems to have been making a sly commentary on the familiar Hollywood tendency toward endless repetition. In reality, old dark house films replete with burglars, monsters and secret passageways had been all the rage in the American film industry through the 1920s and the end of the silent era, but as with so many other genres the arrival of sound created a talkie revival, with The Old Dark House as a new ur-template: One part parody and one part sincere thriller, expanding upon the elements of films like The Cat and the Canary while attaching major stars of the day (Boris Karloff, Charles Laughton) to a familiar story. The classic tropes are all there: A dark and stormy night; a group of strangers in a mansion; mistaken identities; disfigurement; a family secret. Elevating those elements is Whale’s considerable directorial talent, employing the same Expressionist-inspired use of darkness and shadow so often praised in the better-known Frankenstein or Bride of Frankenstein. The Old Dark House, in fact, seems like a film tailor-made for Whale’s beautifully atmospheric black-and-white visuals, all the more impressive now with modern restoration. —Jim Vorel

53. La Chienne (1931)Director: Jean Renoir

If there’s anything about La Chienne that could use tweaking, it’s the ending, or the endings, which occur in a procession of climaxes and resolutions that each trick you into thinking the film is about to end. Most films, even very good ones, could stand to be a few minutes longer. La Chienne could stand to be a few minutes shorter. Let’s be fair, though: La Chienne is the second sound film of Renoir’s career, the first being On purge bébé, a 46-minute comedy about a constipated baby, made five years after the commercial failure of 1926’s Nana. He made other films between Nana and La Chienne, but La Chienne feels like an essential component of his recovery post-Nana and a testament to his mastery of craft. It took him only two movies to get the swing of sound as an element of cinema, though La Chienne employs it so skillfully you’ll be gulled into thinking he’d been making sound films for years beforehand. La Chienne is a beautifully made (if protracted) film about horrible, ugly people, a story of jealousy, greed and deceit that’s shot with the incomparable skill of one of the medium’s true legends. It’s a snapshot of Renoir’s movie history, the moment when Renoir truly became Renoir. By extension it’s also a snapshot of the whole medium’s history, an example of how sound can change a picture, and a lesson in film school well worth attending. —Andy Crump

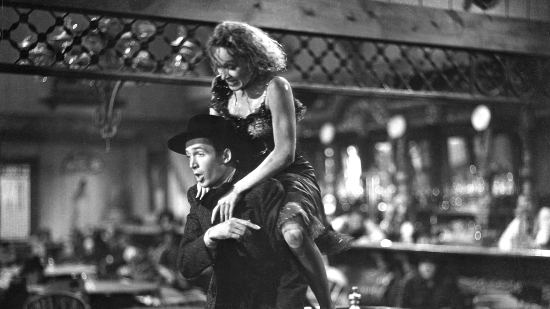

52. Destry Rides Again (1939)Director: George Marshall

Blazing Saddles obsessives: You owe it to yourself to watch Destry Rides Again. There are some obvious connections, like how in Blazing Saddles, Madeline Kahn seems to lift her sultry yet chronically fatigued German saloon entertainer pretty much directly from Marlene Dietrich’s Frenchy, a firecracker who can certainly hold her own in a barroom brawl. (Quite a progressive character for a 1930s Hollywood Western.) Then there’s director George Marshall’s light, slapstick-inflected touch with a Western 101 premise—new sheriff (Jimmy Stewart) rolls into a rowdy town to set it straight—which helped make Destry Rides Again a massive hit, as well as set a new tone, drawing a delicate line between parody and tense drama, for the genre without jeopardizing the audience’s grounded connection to his characters. (The fact that it revitalized Dietrich’s then-dead career is the cherry on top.) Look to the film’s many fight sequences, full of outrageous yet carefully choreographed chaos, and it’s hard not to see the scene in Blazing Saddles where we’re introduced to Rock Ridge. (All that’s missing is an old woman getting beat up while complaining, “Have you ever seen such cruelty?”) Marshall delivers an infectious atmosphere of fun, while Dietrich and Stewart employ their natural charms in service to some dynamite chemistry. —Oktay Ege Kozak

51. A Christmas Carol (1938)Director: Edwin L. Marin

There have been more than 20 adaptations of the Charles Dickens classic holiday morality tale, but only one (Bill Murray’s Scrooged) clearly tops this early talkie from MGM. A familiar tale that helped turn the Christmas season into a time of social charity and humanitarianism, this is a genuine holiday classic.—Staff

50. The Awful Truth (1937)Director: Leo McCarey

One of the best comedies of 1930s Hollywood, The Awful Truth feels fresh more than 80 years after its release, most likely due to director Leo McCarey’s love for cultivating an improvisation-heavy set and keeping his actors on their toes. Even though his film was based on a hit Broadway play, McCarey constantly threw out chunks of the script and made up new scenes on the spot, which disoriented his cast to the point that stars Irene Dunne and Cary Grant became paranoid and anxious about the quality of their performances, since they were rarely allowed to spend enough time rehearsing their lines and getting to the bottom of their characters. This got to a point where Grant tried to get out of his contract because he thought his performance was going to be an embarrassment. This anxiety was exactly what McCarey sought from his actors, which infused this whimsical tale of a couple (Dunne and Grant) on the brink of divorce, sabotaging each other’s romantic interests, with manic immediacy that created some unforgettable lines and gags. Consider a scene where Dunne’s character awkwardly dances in front of Grant and his character’s love interest, making a fool of herself. The comedy of the scene comes from the character’s utter lack of finesse, an unmitigated feeling Dunne derived from being told to perform the dance on the spot. Even though it’s not as memorable or groundbreaking as Make Way For Tomorrow, McCarey’s other 1937 production, The Awful Truth is prime ’30s screwball, thanks largely to the strong chemistry between Dunne and Grant.—Oktay Ege Kozak

49. Sylvia Scarlett (1935)Director: George Cukor

Before Bringing Up Baby, before The Philadelphia Story, Cary Grant fell for Katharine Hepburn as a boy in Sylvia Scarlett. It’s directed by George Cukor, who was at that point the unofficial social director of gay Hollywood. Obvious transmasculine resonance of The Boy Kate aside, there’s also Cary Grant’s fabulous vocal drag as he slides in and out of a Cockney accent and deeper into a wonderfully bewildering T4T, con-artist-on-con-artist vibe. (Kate kisses Dennie Moore, too, just to keep the score even.)—Daniel Mallory Ortberg

48. Westfront 1918 (1930)Director: G.W. Pabst

Is Westfront 1918 the better-made Pabst film or is it just better preserved? Compared to Kameradschaft, the 2K restoration of Pabst’s trench warfare reenactment looks downright pristine, and even then it’s still cobbled together using a duplicate negative. Maybe praising Westfront 1918’s crisper image quality isn’t fair when we’re talking about movies necessarily stitched up using the spare parts our international film archives have in their possession. But Kameradschaft and Westfront 1918 are different movies not only in terms of the quality of their restorations, but in terms of their purposes. Kameradschaft nearly counts as a feel-good movie, though it takes place primarily beneath the earth, in the dark, where all is engulfed by flames. (The Hell motif isn’t easily missed.) Westfront 1918 takes place within a different kind of Hell, wherein you’re stuck in a ditch with comrades, lobbing explosives at enemies who occasionally turn out to be your allies. If you’re lucky enough to go home, you’re actually not lucky at all, because “home” has morphed into a barren pit of starvation and hopelessness. There’s no reprieve from the soul-sucking awfulness of war, not even in the arms of your wife, mostly because her arms are full of the butcher and his meat. (Not actually a play on words, but close enough.) Kameradschaft ends with a warm, life-affirming celebration. Westfront 1918 ends with literal madness and heartbreaking regret. Both films are rooted in actual events, but Westfront 1918’s vision of war’s boundless ruin ultimately feels all too real. —Andy Crump

47. The 39 Steps (1935)Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Before Alfred Hitchcock came to America and made some of the greatest thrillers ever, he had a lucrative filmmaking career in England, including many films American audiences still haven’t seen. One of his finest was The 39 Steps, where a man attempts to help a secret agent, but once the agent dies, the man is suspected of murder and goes on the run. While it may sound similar to other Hitchcock films, like North By Northwest, The 39 Steps is one of the most perfect combinations of Hitchcock’s shocks and bitingly witty scripts.—Ross Bonaime

46. The Water Magician (1933)Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Better known for his later films like Ugetsu, Japanese master Kenji Mizoguchi found his voice early on. He crafted this bleak romance with a rich sense of people and place—in this case a troupe of touring performers in provincial Japan. Irie Takako is captivating as the title character, a performer trying to pay her long-distance love’s college tuition, during good times and increasingly bad ones. Japanese silent film includes the tradition of the benshi, a live storyteller who would describe details of the story and recite dialogue while music played. It makes for a unique—if sometimes overly wordy—way to experience a film. —Jeremy Mathews

45. Dracula (1931)Director: Tod Browning

At this point, director Tod Browning’s Dracula has become such an indelible cornerstone of pop culture that it’s nearly impossible to view the film separate from its iconic standing. Yes, the film is a classic for a reason, but how does it really stand up? Let’s start with the obvious—Bela Lugosi is phenomenal in the title role, oozing charisma with an ever-present undercurrent of menace. As a studio, it’s Universal’s greatest shame that, despite perfecting his Dracula on stage throughout the late 1920s, Lugosi only secured the role after some heavy lobbying and the departure of several potential actors. In fact, the lone downside to Lugosi’s towering presence is that, when he’s not onscreen, the movie becomes significantly less interesting. That’s not the fault of the cast, who all turn in decent performances, but it’s like a talented college basketball player playing one-on-one with Michael Jordan at his prime—even the best are bound to look amateurish by comparison. Besides Lugosi, the other MVP of the film is cinematographer Karl Freund, who complements Lugosi’s presence with a shadowy, Gothic look that would go on to haunt moviegoers’ dreams for decades afterward. And while the much-celebrated Spanish version of Dracula unquestionably made bolder creative decisions, it’s Lugosi’s performance that elevates this production from an effective adaptation to a cultural landmark. —Mark Rozeman

44. Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933)Director: Mervyn LeRoy, Busby Berkeley

Sharply hilarious, pre-Code musical Gold Diggers of 1933 is one of the best representations of choreographer Busby Berkeley’s over-the-top majesty. The Depression-set fantasy (about financing a production, marrying rich and simply making it through the day) is filled with glamour and vulgarity—and actual currency. The “We’re in the Money” number is so catchy and coin-filled that you’ll be jingling long after the movie ends. Aside from the lavish and intensive soundstages, its humor and game cast (Ginger Rogers solos like a star) help set it apart from Gold Diggers of 1935 and Gold Diggers of 1937, both of which also feature geometric and inventively vaudevillian work by Berkeley. An extravaganza atop a career’s worth of extravaganzas.—Jacob Oller

43. The Champ (1931)Director: King Vidor

King Vidor, critically beloved director of silent and early sound Hollywood, had a critical and commercial success on his hands with this Academy Award-winning film. Penned by well-respected female screenwriter Frances Marion, The Champ is an archetypal tale of a floundering has-been fighter (the legendary Wallace Beery) stuck in the bottom of a bottle. In an attempt to live up to the devotion of his young son (Jackie Cooper), who is on the verge of being taken away by his estranged mother, the broken-down Beery fights one last battle to prove his worth. A poignant film on the father-son bond and the powers of forgiveness, The Champ went on to inspire a whole series of similar redemption narratives in ’30s Hollywood. —Christina Newland

42. The Nail in the Boot (1932)Director: Mikhail Kalatozov

Now famous in cinephile circles for lush visual works like The Cranes are Flying (1958) and I Am Cuba (1964), Mikhail Kalatozov’s reputation might go back further if Stalin’s regime hadn’t repressed his films. His rural documentary Salt for Svanetia (1930) and war drama The Nail in the Boot were both banned for favoring “formalistic aestheticism” over “dialectical materialism.” Luckily, the films survive and we can now see this story of a soldier failing in his mission because of poorly-made footwear in all its formal and aesthetic glory. Both the army sequences and, somehow, even the courtroom scene at the end burst with passion and flare. —Jeremy Mathews

41. My Man Godfrey (1936)Director: Gregory La Cava

Gregory La Cava’s My Man Godfrey is kind of like a proto-Le Dîner de Cons—or Dinner for Schmucks—except that My Man Godfrey is really good and neither the latter nor the former film measure up to it. La Cava’s inroads to skewering the upper crust is through the upper crust itself: The film takes its outsider protagonist, Godfrey “Smith” Parke (William Powell), who’s not an outsider at all but a man in exile from high society’s bosom, and inserts him into circumstances where he’s the sanest, sharpest man in the room. Rich people are wild. That’s the film’s subtext, or just its text, because Godfrey’s charges, the members of the family Bullock, are either completely out of their gourds or stuffed headfirst up their own asses. They’d have to be, perhaps, to mistake him for a vagrant when he’s actually a member of the elite class just like they are. They’d also have to be observant and considerably less self-absorbed to make these fine distinctions. La Cava has fun with the scenario, as does Powell, and as does the rest of the cast, in particular Carole Lombard, playing young Irene, who falls head over heels for Godfrey, blithely unconcerned with his disinterest, and Gail Patrick as the daffy Mrs. Bullock, full of unfettered, dizzying joy. Dizziness, of course, is a requirement. Films like My Man Godfrey, screwball joints that move at a laugh-a-minute pace, demand the exhaustion of their viewers, and La Cava wears us out as surely as he delights us. —Andy Crump

40. Drácula (1931)Director: George Melford

It’s crazy to imagine a film being shot multiple times, with different casts and in different languages, today but this was once common practice. Thus was born the Spanish version of Universal’s classic Dracula. It features an entirely different cast—no Bela Lugosi as Dracula or Dwight Frye as Renfield—but filmed on the exact same sets, with the same script. The Spanish crew was literally filming at night, after the English-language crew had gone home for the day. It’s remembered today because of the visual transformation it undergoes: Director George Melford ultimately proved much more active and experimental than Tod Browning, the director of the English-language version, which imbues the Drácula with significantly more interesting and challenging cinematography. Many shots that are simply static in the Browning Dracula (which is a bit of a stuffy movie, although extremely important historically) are given a new lease on life in the Spanish version. The performances are also solid, although unsurprisingly they’re nowhere near as iconic as Lugosi. Watching the Spanish version, you can’t help but wish for a third version of the 1931 Dracula—starring Lugosi and Frye, but directed by Melford. With that combination, perhaps it would be Dracula and not Frankenstein hailed as the crown jewel of the original Universal monster series.—Jim Vorel

39. Swing Time (1936)Director: George Stevens

For better and worse, RKO musical Swing Time, the duo’s sixth film of nine together at the studio, represents best the tenure of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire’s partnership. An international box office success, about the troubled courtship of kindhearted gambler Lucky (Astaire) and hardheaded-until-she-isn’t dance instructor Penny (Rogers), Stevens’ spectacle for his two icons features a breathtaking dance with Astaire’s only cinematic set piece ever performed in blackface (ergh) and a joke/crucial narrative point having to do with cuffs on mens’ trousers that is so dependent on fashion mores of the 1930s—not to mention, so important to the success of our whole love story—one might wonder retroactively if the bottoms of mens’ pants were intended to be a more plangent metaphor buried within an otherwise stupid plot. They weren’t—because nothing is that deep in Swing Time. But such is the stuff of the immense surface pleasures of the film, of its ravishing sets shot magnanimously by David Abel, of its snowbound urban din conveying all kinds of warmth and texture, of the ways in which the characters are unable to express their big feelings in small words, so their whole world conspires to showcase the synchronicity of their bodies in motion. It takes about 25 minutes for all the pieces to align to give us our first musical number, but once it begins, far be it for any of us to question the calibration—the preternatural space-time precision—with which Astaire and Rogers are deployed. For many, this may be their first encounter with the two stars’ films; no one expects the Mr. Bojangles homage until they do. Regardless, Swing Time’s endured for its skin-deep bliss, and even today we’re unable to look away. —Dom Sinacola

38. Vampyr (1932)Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer

While wandering the countryside, a naïve young man with a propensity for the occult stumbles upon a castle where he learns that the owner’s teenage daughter is slowly descending into vampirism. Upon seeing the village doctor trying to poison the girl, the boy intervenes and complications, naturally, ensue. Notable as being one of the few early vampire movies not even passingly based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Vampyr nonetheless brought very little joy to its creator, legendary Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer (The Passion of Joan of Arc). Forced to shoot the production in three different languages (French, German and English), Dreyer’s first sound film experience was a proverbial trial by fire. To add salt to the infuriating production, the film was released only after some fairly heavy censoring. The reception was no less brutal, with critics delivering scathing reviews. As the years have passed by and an appreciation for Dreyer has grown, however, so has an appreciation for the film, with many modern critics citing its subversive take on sexuality to be years ahead of its time. Shot with the delicacy and elegance of a dream, Dreyer quickly plunges the viewer into an expressionistic hellscape of shadows and dread. Though it may be a bit slow for some audiences, even with a sparse 73-minute runtime, Vampyr is a intense mood piece that picked up where Nosferatu left off. —Mark Rozeman

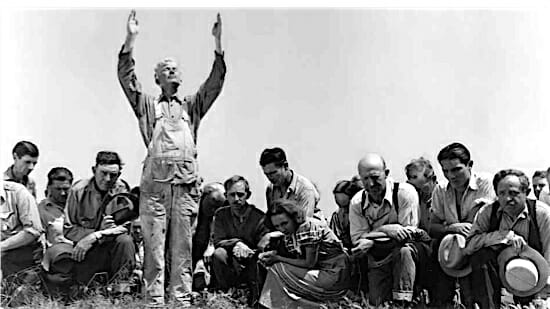

37. Our Daily Bread (1934)Director: King Vidor

King Vidor, one of the most respected filmmakers of silent and early sound Hollywood, caused a stir in Depression-era U.S.A. with this remarkable Communist parable. In this celebration of the power of the collective, Vidor imagines a group of unemployed Americans coming together to dig an irrigation ditch and thus enrich their farm with healthy wheat crops. It’s not exactly the most commercially thrilling material, but it’s a sincere and idealistic little story of homespun hard work and the triumph of the “little guy.” Vidor always worked with bold visuals in mind, and Our Daily Bread delivers in that regard—offering an almost avant-garde montage sequence part of the way into the film. —Christina Newland

36. Kameradschaft (1931)Director: G. W. Pabst

Kameradschaft starts suddenly, as these things do: Deep beneath the earth, in a mine located on the border separating Germany from France, itself divided into two distinct sections based on nationality, a fire smolders. The French build walls around it to contain it, but you can’t contain fire with brick forever. Eventually, the mine explodes and collapses, trapping French miners in droves, their families on the surface watching smoke billow from the mine in helpless awe. Kameradschaft is one of the form’s early disaster movies, and like contemporary disaster movies it hones in on humanity uniting in the face of common catastrophe. (It’s also based, if loosely, on an actual disaster, the Courrières mine disaster of 1906.) The Germans put together a team to save the day, convincing their bosses and their countrymen that intervening is simply the right thing to do. Borders don’t matter. Tensions between nations don’t matter. Risk to life and limb doesn’t matter. (Wittkopp [Ernst Busch], the German miner leading the effort to rescue the French, proclaims that they’d come to his aid if the shoe was on the other foot.) But those tensions have to be established before any thrilling heroics take place, whether in a game of marbles between bickering sons of French and German border guards or in a beer hall misunderstanding. The tensions chafing both countries are palpable. The note of humanity on which the film ends, which is more like a full-blown symphony, reveals them as wastefully petty. It’s a cathartic moment that still applies more than eight decades after its release. —Andy Crump

35. Land Without Bread (1933)Director: Luis Buñuel

Ever since the Maysles and Frederick Wiseman and D.A. Pennebaker became direct cinema heroes in the 1960s, cinéma vérité has become something of a default method for documentary filmmakers—the less mitigated the experience, the more illuminating the truth. But the further one digs into the form’s origins, the more an ethnography like Luis Buñuel’s Land Without Bread begins to rear its suspiciously exaggerated head. An exploration of the Las Hurdes region in Spain, where inhabitants are steeped in such poverty that the idea of “bread” is alien to them, Buñuel’s account is part travelogue, part surrealist parody of the kinds of over-exoticized travelogues of the time. In attempting to describe the extent of the region’s scarcity (where one practice is to take in random orphans in order to claim the government welfare that accompanies them), Buñuel spares no brutal detail, setting out to make these peoples’ lives seem as excruciating as possible. Undoubtedly over the top, yet terribly stirring, the film claims that one doesn’t have to look far to find a compelling documentary subject—sadness and devastation can be found right in your backyard. —Dom Sinacola.

34. Dragnet Girl (1933)Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Yasujiro Ozu isn’t generally thought of as a gangster film director, but that’s not the only thing that makes Dragnet Girl so interesting. Ozu pays tribute to the American genre, but doesn’t strictly adhere to it. He creates a weird hybrid setting that’s like an American Japan, and populates it with characters facing genuine moral dilemmas. Working with high stakes, Ozu makes a film that’s more urgent in plot than his familial dramas, but no less artful. —Jeremy Mathews

33. The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)Director: James Whale

Egregiously omitted from most “best sequel” discussions, this darkly inventive would-be love story may well be the finest of the golden-age Universal monster movies. With its extravagant Gothic aesthetic and timeless Hollywood mores (“We belong dead!”), the film is the face of an era and a fearsome inspiration to many that followed.—Sean Edgar

32. The Blood of a Poet (1932)Directors: Jean Cocteau

Jean Cocteau’s surreal avant-garde masterpiece about the burden of artistic creativity lays out, with dizzying glimpses of grace and terror, the bitter yet honest facts about our creations. Mainly, that they might be more in control of us than we are of them, and that, if we’re lucky, they will outlive us to breathe new life onto themselves. Cocteau’s tricky use of in-camera effects to create fantastical dream logic imagery, like a hand that gains a mouth or a mirror that works as a portal to an artist’s subconscious mind, is a treasure trove for fans of David Lynch’s work. Especially if the final season of Twin Peaks was your bag, you pretty much owe it to yourself to check out The Blood of a Poet. —Oktay Ege Kozak

31. Trouble in Paradise (1932)Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Lubitsch’s masterpiece about class, status and seduction focuses on two thieves who fall in love while masquerading as nobility throughout Europe. Made before the Hays Code, it’s a boldly sensual film, with a sexual charge to much of the dialogue and a frank depiction of romantic mores—in fact, once the code was adopted in 1935, the movie was effectively banned from rerelease until the late ’60s. Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins play refined crooks who try to swindle a wealthy widow played by Kay Francis, with romantic and sexual complications arising from Francis and Marshall’s growing relationship and the presence of Francis’s other suitors. It’s a smart, seductive film, with a gorgeous ambiance and a script that sees through the bluster and artificiality of the social hierarchy. It’s also still funny to this day. —Garrett Martin

30. Son of Frankenstein (1939)Director: Rowland V. Lee

Deciding which of the classic Universal Monster movies should be featured on this list proved an incredibly difficult proposition. Notably absent is James Whale’s 1931 classic Frankenstein. Why? Well, despite what you may have heard, Frankenstein may very well be the third best film of its own series, surpassed not only by the well-recognized Bride of Frankenstein but also by the much less appreciated Son of Frankenstein as well. Director James Whale and original Dr. Colin Clive have moved on, the latter replaced by classic Sherlock Holmes portrayer Basil Rathbone as our new protagonist, Wolf Frankenstein, who returns to his father’s ancestral castle only to find that the legendary monster isn’t quite as dead as he’s been led to believe. Bela Lugosi, of all people, enters the series as the first Frankenstein character called “Igor” (although it’s actually “Ygor”), a ghoulish caretaker who claims to literally be undead—hanged by the villagers and sustaining a broken neck, but somehow not dying. His master plan: To use Wolf’s scientific knowledge to resurrect the monster (Boris Karloff, one final time) and then use the monster as a tool of vengeance to hunt down the men who hanged him. With cavernous, opulent sets in Frankenstein manor, Son of Frankenstein is a lush, prestigious-feeling production that boasts masterful performances from Rathbone, the one-armed inspector (parodied in Young Frankenstein) played by Lionel Atwill and especially from Lugosi, who is at his absolute best in a role that is far more nuanced than that of Dracula. With its gorgeous, gothic visuals and expanded run-time, Son of Frankenstein is the secret crown jewel of the entire Universal Monster series. —Jim Vorel

29. The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939)Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

The same year that saw American cinema classics Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz released gave us legendary Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi’s sublime masterpiece of Japan’s “monumental style.” In The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum, with Imperial Japan at its most jingoistic, the director has quietly retreated from the looming threat of bellicose nationalism, choosing instead to craft an exquisite cinematic monument to traditional kabuki theatre. Mizoguchi’s camera is a wonder—moving with the same elegance and aching patience of kabuki—and the Criterion team’s restoration and 4K transfer is stunning, the best that could be struck from reclaimed positive and negative prints of the 1939 film. Nearly 80 years later, Chrysanthemum reveals itself to be as subversive in regards to gender as it is so politically, with a heartbreaking story of one woman’s unrequited sacrifice sure to leave viewers shaken. —Chris White

28. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)Director: Lewis Milestone

Such was the impact of Lewis Milestone’s pacifistic WWI drama: When the film was first released, Variety wrote that the League of Nations should show it around the world “until the word ‘war’ is taken out of the dictionaries.” Not surprisingly, the fascist regimes of Germany and Italy banned the movie—they feared the influence of its anti-war message, and, 90 years on, the pulverizing power of the film is obvious. All Quiet on the Western Front is ferocious, a Pre-Code deglamorization of war that, some nine decades ago, arguably made the final point on the profound horror of the trenches. The heroes of this tale start out as schoolboys, young Germans urged to the front by their professor, but—without the film ever sparing much time to contemplate just what’s happening—before long the class of ’14 are whittled down to just one veteran boy soldier, a witness in his teens to all the myriad ways men can die. Just out of the silent age, Milestone made a noise that can still be heard loud and clear. —Brogan Morris

25. – 27. The Marseille Trilogy: Marius (1931); Fanny (1932); César (1936)Directors: Alexander Korda; Marc Allégret; Marcel Pagnol

Marcel Pagnol’s trilogy can seem a bit tame in comparison with all the influential iconoclasts and film auteurs on this list, but starting with Marius, an adaptation of Pagnol’s stage play, the Marseille Trilogy should be viewed as a trailblazing trio of films in their own rights—films that would provide some of the very standards against which later directors would so gleefully rebel. Immensely evocative in settings both physical (Marseille harbor) and emotional (the relationships between the main characters, requited and not), Marius, Fanny and César take the viewer on a journey that, while a bit melodramatic at times (and of the times, cinematically), both soothes and delights in its capturing of quirks, fancies and flaws that are all too human.—Michael Burgin

24. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933)Director: Fritz Lang

Psychologist Stanley Milgram’s landmark study Obedience To Authority suggested human beings are easily led to do horrible things, especially when a domineering figure is calling the shots. Years earlier, director Fritz Lang came to a similar conclusion with his masterful The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933). By the time Lang made Testament he’d been incorporating the figure of evil authority into many of his films. He contributed to script development for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and went on to explore the theme in Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler (1922), Metropolis (1927) and M (1931). But for Testament, Lang revived the figure of Mabuse, expanding the role of the twisted überman, whose mad genius and hypnotic power prove irresistible even to medical science. The film begins with Mabuse confined to an asylum, spending his days in a catatonic state and scribbling his plans for an “empire of crime.” As his blueprint for anarchy begins to come to life in a string of illegal acts, the dogged Inspector Lohmann (Otto Wernicke reprising his colorful role from M) is called in to crack the case. Lang’s sly incorporation of elements from another great German commentary on totalitarianism, Dracula, makes his intensions all the clearer (including hypnotism and the clear parallel to the lunatic Renfield in the role of Hofmeister). It’s no surprise Joseph Goebbels immediately banned the film, causing Lang to flee Germany and the Third Reich. One of the great fascist cautionary tales ever committed to film—and it doesn’t hurt that it’s also an endlessly entertaining potboiler. —Tim Sheridan

23. City Lights (1931)Director: Charles Chaplin

In his later years, Charlie Chaplin was known for bringing pathos into his comedy whenever he had the opportunity. City Lights is the movie where he earns every bit of it. While its structure resembles Chaplin’s usual picaresque format, there’s more of a deliberate purpose as the tramp tries to help a poor, blind flower girl, played adorably by Virginia Cherrill. Harry Myers also deserves a mention for his performance as the millionaire who’s generous when he’s drunk and can’t remember his good deeds when he’s sober.—Jeremy Mathews

22. Only Angels Have Wings (1939)Director: Howard Hawks

Only Angels Have Wings has all of the markings of a long line of great Howard Hawks films. The snappy dialogue pops and is fast-paced, the women are independent and strong, the visuals are the best around and the experience is only which the likes that Howard Hawks can deliver. There is no shortage of great films by Hawks, but with Only Angels Have Wings we can see a bridge between his films of the ’30s with what was to come throughout the next two decades. Quentin Tarantino referred to Hawks’ Rio Bravo as the great “hang-out” film, although Angels is a close second. The characters feel like people we’re in the same room with, as if we’re in Dutchy’s bar having a drink with the gang. Life simply seems to go by while the piano pounds away. Cary Grant and Jean Arthur provide fantastic performances, although Thomas Mitchell’s “Kid” Dabb might be the greatest joy to watch, and Rita Hayworth in a breakout performance is no less engaging. You can just feel this film—every fiber of it comes alive.—Nelson Maddaloni

21. Duck Soup (1933)Director: Leo McCarey

Although some critics would argue that Duck Soup’s pacing make it inferior to other films in the Marx catalog, the film’s incredible one-liners and the brothers’ great on-screen chemistry make it one of their most clearly beloved films. The audience sees Groucho’s spitfire mouth in its prime as Rufus T. Firefly, a newly appointed leader of the struggling country Freedonia, and it’s as much a solid chunk of hilarity as it is a satire of government and politics of the time. Harpo and Chico are incredible in their secondary parts as spies, showcasing their hold on slapstick and physical comedy that’s most pronounced in Harpo’s hilarious, near-blank facial expressions throughout. —Tyler Kane

20. Happiness (1934)Director: Aleksandr Medvedkin

To watch a Soviet silent comedy, you must be prepared for some zany surreality. I don’t know how or why, but from My Grandmother (1929) to The House on Trubnaya Square (1928) to The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924), these U.S.S.R. laughers reliably go off the rails, then tie the rails in a knot for good measure. With Happiness, Aleksandr Medvedkin delivers plenty of oddity as a hapless farmer struggles to find his place in society, even after his horse-wife finds hers. But Medvedkin also reigns the film into a better-shaped and tighter-focused narrative than most of his contemporaries, making this the most successful work of the genre. —Jeremy Mathews

19. Bringing Up Baby (1938)Director: Howard Hawks

The textbook example of a screwball comedy, Bringing Up Baby finds Cary Grant’s hilariously uptight paleontologist Dr. David Huxley struggling to keep his life together when the flirtatious agent of chaos that is Katherine Hepburn’s Susan Vance comes crashing into his life. Add in shenanigans involving a baby leopard, a collapsing brontosaurus skeleton and some deftly executed pre-MPAA sexual innuendos and you have not only one of the best romantic comedies of all time but one of the funniest American movies ever made. —Mark Rozeman

18. Freaks (1932)Director: Tod Browning

Tod Browning used actual circus performers in this story of a gold-digging trapeze artist who deviously cons a dwarf and exacts the revenge of his malformed friends. Resurrected by the Ramones (Gabba gabba hey!) and U2 (“All I Want Is You” video), the film still shocks and scares three-quarters of a century later, thanks to a menacing climax and a gloriously macabre ending. —Sean Edgar

17. Zero for Conduct (1933)Director: Jean Vigo

Sometimes called the Patron Saint of French Cinema, Vigo died at 29 from tuberculosis having directed just one feature and three shorts. There’s no other figure in film like him, and despite his minuscule output, Vigo went on to inspire many directors from Francois Truffaut to Lindsay Anderson. His masterpiece was Zero for Conduct, which tells the story of a boarding school revolt, beginning with an explanation of why the students feel rejected and leading up to an extraordinary series of scenes in which they take control. Vigo’s jokes create the narrative, and the film is freewheeling and whimsical. At the same time it’s tightly plotted and each scene serves a direct purpose. Rarely have children been directed so well, and Zero for Conduct’s absurdist tendencies never get the better of its underlying points. The film’s end in particular is spectacular and memorable, both in the stylistic boldness of the way it’s filmed and the way it confounds narrative expectations. Zero for Conduct is absolutely brimming with life. —Sean Edgar

16. King Kong (1933)Director: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack

There had been monster movies or “creature features” before Kong, but it became the key reference point for that entire film demographic from the time of its release until the genre underwent an atomic-age reimagining with the likes of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in 1953 and Them! in 1954. Likewise, it set the bar on its special effects at such a high level that in many instances, shots and sequences from King Kong weren’t suitably duplicated for decades to come. Much of the credit belongs to pioneering stop-motion animator Willis O’Brien, who was inventing new techniques on the set of Kong on a daily basis, laying a foundation for an entire field of visual effects that are still being refined by studios such as Laika today. Those techniques were likewise carried on and further refined by O’Brien’s arguably more famous protégé, Ray Harryhausen, who used them to great effect in the second golden age of the monster movie, from the 1950s through the 1970s. Kong, though, stands as an unparalleled achievement for its time—far grander and more ambitious in scope than most anything you can compare it to back then. On one hand it’s a rollicking adventure film, with a classic “journey into the unknown” plot that is still being recycled for modern monster installments like Kong: Skull Island. At the same time, though, it was likewise an interesting experiment in genre-blending—an FX-driven adventure-drama film with horror elements and no clear-cut, traditional “antagonist.” Carl Denham might fit the bill, but he’s better described as a naïve dreamer with stars in his eyes, oblivious to the ethical quandary of shanghaiing a huge beast to display in the middle of New York City. Kong, meanwhile, is a misunderstood creature, operating on the sense of self preservation he learned in a home where he’s only ever known a daily fight for survival against a neverending stream of monsters. The film’s empathy for Kong, and its condemnation of the hubris that led to his ascent of the Empire State Building, are what helped make the story such an emotionally affecting classic. —Jim Vorel

15. It Happened One Night (1934)Director: Frank Capra

Frank Capra’s screwball romantic comedy established the quintessential format for the lighthearted American romantic movie: Base it around a couple of stars with a great on-screen connection (even though Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert apparently didn’t get along too well behind the scenes), add some witty banter and a bit of raciness, and you’re most of the way there. The greatest contribution of It Happened One Night was likely in allowing Colbert’s comedic sensibilities and capability as a character to shine just as brightly as Gable’s—in that, it’s a surprisingly progressive film for its day. She, of course, gets the most famous and influential moment, when she shows up the know-it-all Gable by showing a little leg to successfully hitch a ride. That one moment has echoed through the romantic comedy genre ever since.—Jim Vorel

14. Angels With Dirty Faces (1938)Director: Michael Curtiz

Jimmy Cagney, Pat O’Brien and Humphrey Bogart star in this early entry in the noir canon, a surprisingly restrained morality play about two childhood friends whose lives take different yet intersecting paths. During their youthful delinquent days in Hell’s Kitchen, Cagney’s Rocky took the rap for a railroad car robbery after saving the life of his pal Jerry (O’Brien), who subsequently got away—he “couldn’t run as fast as I could,” Jerry laments guiltily. Years later, Rocky is out of juvey and back into crime—along with his new associate, lawyer/heavy Bogart—while Jerry has become a man of the cloth. The priest is doing his best to discourage the neighborhood’s street kids, AKA the “Dead End Kids” and “Bowery Boys” of several film series, to learn from his mistakes. Instead, the fledgling hoodlums idolize Father Jerry’s former BFF, who eats up the attention. What distinguishes Angels With Dirty Faces from its earlier, clear-cut gangster peers (e.g., The Public Enemy) is an emotional, redemptive thread, along with the focus on forces, both internal and external, upon the characters’ fates. A social conscience and introspection elevate what in lesser hands than Michael Curtiz’s would be a contrived melodrama. That, and a smartly paced production led by performances from O’Brien and, particularly, Cagney, whose charismatic turn—check that up-for-interpretation climactic reckoning—landed him his first Best Actor Oscar nomination. —A.S.

13. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)Director: David Hand, William Cottrell, Wilfred Jackson, Larry Morey, Perce Pearce, Ben Sharpsteen

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was by no means the first major animated film, but it was the first full-length cel animated feature, and every animated feature afterward is its scion. Before Snow White, “cartoons” were simply part of the filler and previews one might see before an actual feature. Disney’s animation team showed what could be accomplished with an entire staff of talented artists working for an extended period on a united goal, and the film’s massive box office success proved that animated features were a valid and potentially lucrative business. Regardless, “animated film” implied an entirely different meaning in the post Snow White film industry.—Jim Vorel

12. The Lady Vanishes (1938)Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Pretty much predating every trope you’ve ever come to expect out of a genre that gets its name from keeping the audience keyed-up, The Lady Vanishes is both hilariously dated and a by-the-numbers primer on how to make a near-perfect thriller. Far from Hitchcock’s first foray into suspense, the film follows a soon-to-be-married woman, Iris (Margaret Lockwood), who becomes tangled in the mysterious circumstances surrounding the titular lady’s disappearance aboard a packed train. No shot in the film is extraneous, no piece of dialogue pointless—even the ancillary characters, who serve little ostensible part besides lending complexity to Iris’s search for the truth, are crucial to building the tension necessary to making said lady’s vanishing believable. The film is a testament to how, even by 1938, Hitchcock was shaving each of his films down to their most empirical parts, ready to create some of the most vital genre pictures of the 1950s.—Dom Sinacola

11. L’Age D’Or (1930)Director: Luis Bunuel

Just like it is with Un Chien Andalou, it’s futile to draw any form of a cohesive narrative structure out of Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel’s fever nightmare takedown of respected social norms. From the moral emptiness of the bourgeoisie, Bunuel’s favorite subject, to a giddy ridiculing of the Catholic church, the point of L’Age D’Or is to extract strong visceral reactions out of the oppressively controversial images that Dali and Bunuel throws at us. Uncut cinematic surrealism like this is better consumed in shorter bursts, Un Chien Andalou’s 16-minute runtime a perfect specimen, so L’Age D’Or’s one-hour runtime tests out patience at points. Yet as the final collaboration between two of the most formidable surrealist artists of the 20th century, its place in film history is indisputable. —Oktay Ege Kozak

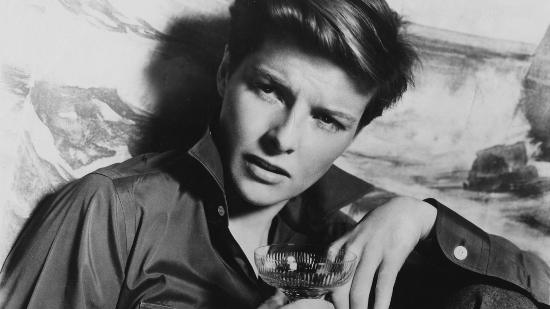

10. Young Mr. Lincoln (1939)Director: John Ford

John Ford—embodiment of the American ideal; institutional director favorited by hardened cinephiles, casual film lovers and old-school auteurs like Sergei Eisenstein alike—does not cater too obliviously to the iconography of Abraham Lincoln (played by Henry Fonda as if Lincoln could’ve been the most charming union organizer any budding socialist has ever seen). Instead, Ford studies the moral mettle of Lincoln from a functional perspective: How does someone become a beloved member of a community? How does a homey sense of logic carve out the crucible of justice? Which pie was better, the apple or the peach? In Ford’s film, which rides the rails of both biopic and a sort of ur-text for a true-crime procedural, Fonda’s Lincoln both occupies each frame and limns it, serving as the literal centerpiece for a courtroom drama while defining how the many personalities of a burgeoning Illinois town come together to decide the proper way forward. An early scene, in which Lincoln decides the fate of a feud between a farmer and a tenant, the two men seeking legal guidance from young lawyer Mr. Lincoln orbiting Lincoln’s desk, cinematographers Bert Glennon and Arthur C. Miller keep the camera anchored to Lincoln’s long legs, which Fonda casually props up often throughout the film, plopping down on desk and chairs and assorted posts. It’s as if the filmmakers know that Lincoln’s presence—physically, but also more than physically—defines the space in which the future President reclines. The crux of every argument, every ethical dispute, revolves around the man’s body. Criterion’s HD transfer transforms these carefully-blocked scenes into a sumptuous depth of field, eking out every inch of every shabby room Lincoln stretches within. It’s breathtaking stuff, even as the film ends with the trepidation towards the kind of larger-than-life people we’re intent on—with the political world as transparently mutable as it is and history as fungible as it is—re-evaluating today. —Dom Sinacola

9. The Wizard of Oz (1939)Director: Victor Fleming

One of the first movies many can remember as inspiring thoughts of true magic, The Wizard of Oz scampered on the heels of Disney’s Snow White like Toto trotting down the Yellow Brick Road. Encouraged by that fantastical animated movie’s success, The Wizard of Oz brought Oscar-winning songs, a bouncy score, a truly committed villain and inspired effectwork to a live-action Technicolor fairy tale. Like Snow White, its savvy and straightforward wonder is timeless and essential—whether you caught a theatrical re-release or one of its traditional TV airings, you got swept up in the transformative power of its sepia-to-rainbow colors and the youth-to-adult anxieties at its dark core. From its status as a Judy Garland epic of the queer canon to its lasting testament to Margaret Hamilton’s sacrifice as the Wicked Witch of the West, from its earworm tunes to its confident redefinition of L. Frank Baum’s world, The Wizard of Oz could do it all. It welcomes interpretation, yet offers a cheerful surface. It terrifies and delights. It is an American fable writ large, sparkly, expensive, torturous and deceptively cheerful; The Wizard of Oz remains the quintessential fantasy epic of Hollywood.—Jacob Oller

8. Modern Times (1936)Director: Charles Chaplin

If time is a flat circle, then Modern Times is like a flat sprocket—the travails of the Little Tramp navigating a mechanical world being so incessant and repetitive that elements like luck and hope only serve to spur along Chaplin’s farce even though they hold little grip on his characters’ futures. Not much changes for the Little Tramp throughout: He tries to survive, and yet the institutional system craps him back out to where he started, desperately hungry and penniless, left with nothing to do but try again. This was also Chaplin’s last go as the Tramp, and it’s easy to imagine that, throughout the film’s many misadventures—joined by equally good-natured partner in crime, the gamin (Paulette Goddard)—as he gets sucked up and sublimated into the modern industrial machine, this “disappearance” was kind of by design. It’s a weird way for Chaplin’s beloved character to go out, but so is the many ways in which Chaplin shows how the modern industrial machine becomes part of the Tramp, too. He may get squeezed through a giant, sprocket-speckled apparatus, becoming one with its schematics, but so too does the assembly line—with all that twisting, wrenching and spinning—impress itself onto the Tramp, leaving him unable after a long shift to do anything but waggle his arms about as if he’s still on the assembly line. It’s no wonder, then, that the President of Modern Times’ factory setting bears a striking resemblance to Henry Ford: Chaplin, who toured the world following the success of City Lights, witnessed the conditions of automobile lines in Detroit, how the drudgery of our modern times weighed on young workers. The Great Depression, Chaplin seems to be saying, was the first sign of just how thoroughly technology can kill our spirits, not so much discarding us as absorbing our individuality. Modern Times, then, is a film with a conscious far beyond its time, a kind of seamless blending of special effects, sanguine silent film methods and radical fury.—Dom Sinacola

7. The Lower Depths (1936)Director: Jean Renoir

Set in a filthy flophouse, Maxim Gorky’s harrowing 1902 drama, The Lower Depths follows the interactions of a group of forgotten and utterly desperate Russians who have sunken into the dark night of the soul. While Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 version is a fairly faithful adaptation reset in Japan’s Edo period, Jean Renoir took a very different approach when crafting the screenplay for his 1936 adaptation. Renoir’s tweaks to Gorky’s work belie a downright socialist agenda, subtly poking fun at bourgeois society. His thief (played with debonair charm by Jean Gabin) has the air of a Robin Hood about him, as he befriends a down-on-his-luck aristocrat (the great Louis Jouet), who later serves as a wry observer to the self-delusion practiced by denizens of the almost cozy-looking flophouse. Renoir also adds a fat, lecherous bureaucrat in the person of a building inspector and has his landlord frequently point out that he’s “the boss,” a title that is most interesting considering his fate. And where Kurosawa undercuts a moment of happiness with shocking cynicism, Renoir tempers his darkest moment with romantic optimism. It speaks volumes about the two artists and makes for fascinating viewing. —Tim Sheridan

6. The Grand Illusion (1937)Director: Jean Renoir

Made in the build-up to an even greater war, Jean Renoir’s WWI POW drama is a sincere call for unity between nations. The call would go unheeded of course, but 80 years filled with clashes and violent disagreements later, Renoir’s message prevails: class, nationality and creed are meaningless before our shared humanity. Just a decade on from the first talkie, Renoir made what today appears a strikingly modern film: naturalistic performances and dialogue, smooth camera movements and, most importantly, complex character dynamics. Every character in the film, through desperate circumstance, becomes allied with another from a walk of life they otherwise would never traverse. Most interesting is the relationship between the aristocratic de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) and von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim): They are French and German, prisoner and warden, but, as if two rare creatures forced to occupy the same cage, a friendship forms through mutual recognition that they may be among the last of their kind. Renoir’s depiction of an entire society through allegory is genius, his empathy almost superhuman. The Grand Illusion kills with kindness—it fulfills its duty as an anti-war flick not by showing battlefield horrors, but simply by asking: how can we be enemies when we have so much in common? —Brogan Morris

5. Stagecoach (1939)Director: John Ford

And just like that, with one swift zoom shot, John Ford gave John Wayne his breakthrough role and reintroduced American audiences to the man who would become one of their most lasting movie icons. Two Johns, making it happen. Stagecoach isn’t exactly a John Wayne movie, despite John Wayne being in it; this was before the days of The Searchers, of She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, of The Quiet Man, even of Hondo, movies that each helped shape Wayne’s persona and forge his screen legend bit by bit. In Stagecoach, he’s just a man with a rifle, a mission of vengeance and a soft spot for a prostitute named Dallas. Rather than the tradition of Wayne, the film belongs to the tradition of strangers on a journey; it’s about an unlikely and incongruous grouping of humans banding together to make it to a common destination. They ride a dangerous road, but Ford’s great gift as a filmmaker is his knack for making peril buoyant and entertaining, and in Stagecoach he does both effortlessly.—Andy Crump

4. Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931)Director: F.W. Murnau

F.W. Murnau’s final film before his tragic death underlines just how capable he was of adapting from one style to the next. Stepping away from Hollywood, he collaborated with famed Nanook of the North documentarian Robert J. Flaherty, who wrote the screenplay with Murnau and directed the opening scene. Murnau documents the lives and culture of Indigenous Pacific Islanders while also weaving a tragic love story. The quietly harrowing final sequence ensures that the film will never stop lingering faintly in the mind.—Jeremy Mathews

3. The Rules of the Game (1939)Director: Jean Renoir

When Rules of the Game, Jean Renoir’s angry satire against the disregard and contempt the bourgeoisie displays for the working class, was first shown to an audience, a man who heard of the film’s supposed communist message tried to light a fire. Later, Renoir said that if someone is willing to burn down a theatre to destroy your work, you must have done something right. Renoir brilliantly hid his brutally honest takedown of ruling class sociopathy under a thin veneer of a soap opera romance between the rich. Under this gaudy gold-plated surface of civilized behavior, expensive dinners and manly quail hunts, lies a moral rot that abandons all human dignity in favor of crude hedonism. If you’re looking for an artistic guide to understanding how we got to this abysmal point of income inequality, look no further.—Oktay Ege Kozak

2. I Was Born, But… (1932)Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Yasujiro Ozu spent his career making wonderful films about the dynamics of families and relationships, but this one may do its job more adorably than any of his others. It uses a couple of achingly cute kids to examine the compromises of adulthood and the disillusion of growing up. When two brothers realize that their father isn’t the big shot in real life that he is in the house, they lash out with petulance, feeling they’ve been lied to. The comedy comes with a delicate understanding of its characters and the importance of realizing when you’ve hurt someone more than they’ve hurt you.—Jeremy Mathews

1. M (1931)Director: Fritz Lang

It’s rather amazing to consider that M was the first sound film from German director Fritz Lang, who had already brought audiences one of the seminal silent epics in the form of Metropolis. Lang, a quick learner, immediately took advantage of the new technology by making sound core to M, and to the character of child serial killer Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), whose distinctive whistling of “In the Hall of the Mountain King” is both an effectively ghoulish motif and a major plot point. It was the film that brought Peter Lorre to Hollywood’s attention, where he would eventually become a classic character actor: The big-eyed, soft-voiced heavy with an air of anxiety and menace. Lang cited M years later as his favorite film thanks to its open-minded social commentary, particularly in the classic scene in which Beckert is captured and brought before a kangaroo court of criminals. Rather than throwing in behind the accusers, Lang actually makes us feel for the child killer, who astutely reasons that his own inability to control his actions should garner more sympathy than those who have actively chosen a life of crime. “Who knows what it is like to be me?” he asks the viewer, and we are forced to concede our unfitness to truly judge.—Jim Vorel