When you hear the term “monster movies,” you might think you know what to expect. A giant, irradiated bug stomping all over a modern metropolis, perhaps, or an inhuman beast stalking a group of campers foolish enough to blunder into its territory. The connotation of “monster” is a negative one, after all, but it’s also a term that reveals the inherent prejudice of those who use it. A “monster” is simply that which we find exotic, frightening and difficult to categorize—it’s an aberration in the natural order, and with that realization the fear comes naturally. We always fear what we don’t understand, as the likes of H.P. Lovecraft and Carmine Falcone have memorably opined.

A “monster movie,” then, is a bit wider term than one might initially realize, composed of everything from man’s battles against the natural world (as in Jaws) to struggles with the repressed self, as seen in almost any werewolf feature. There are beasts aplenty here, and a smattering of snarling aliens, but also lovable monsters and misunderstood creatures that never wanted to do any harm. Some are unabashed villains, while others are actually the protagonists of their films.

Here are the 50 best monster movies of all time, but first let’s discuss which movies you will and won’t see on this list.

Defining a “Monster Movie”

— The threat or focus of a monster movie has to be something inhuman. Human behavior can of course be “monstrous,” but a monster as we’re defining it here isn’t a human, unless that human has physically transformed somehow. By that token, an earthly animal (like the shark in Jaws, or the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park) can be “monsters,” per se, especially if they’re presented in unrealistically heightened ways, such as being bigger than normal, or operating with unnatural malevolence. A human can also transform into a monster, as in the case of a werewolf.

— Alien creatures, likewise, are also capable of being monsters, but they’re far more likely to qualify if they kill by physically attacking you with tooth and claw. The xenomorph of Alien? Monster. The ray gun-wielding, chattering martians of Mars Attacks? Not monsters.

— The monsters shouldn’t be supernatural in origin. By this token, a ghost is not a monster. Neither is a zombie, as they’re undead and not a flesh-and-blood creature. Disqualifying “undead” in general also keeps vampires off this particular list, but don’t fret: You can visit our list of the 100 best vampire films of all time, or the 50 best zombie movies of all time.

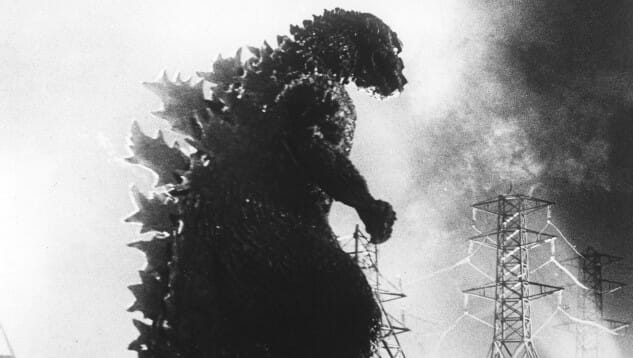

— In order to keep the list from being completely dominated by entries from specific franchises such as the Godzilla series, we will hold ourselves to a maximum of only two entries per franchise. Never fear, we’ve ranked every Godzilla movie in the past, as well.

50. Prophecy (1979)Director: John Frankenheimer

Prophecy qualifies on several odd fronts at once: It’s simultaneously a “nature attacks” rip-off in the vein of Jaws or Grizzly, and also a would-be environmental passion piece, wrapped up in the guise of an exploitation horror movie. Oh, and it also wants to be Alien as well. Suffice to say, it’s a bizarre, jumbled mixed bag, but one that stands out for the oddity of its monster, a mutated, hind leg-walking bear that was transformed by the industrial waste produced by a paper mill. Watching today, it might almost remind viewers of Spielberg’s The Lost World, as the bear monster assumes the role of the T-Rex pair, vengeful and desperate to recover its threatened offspring from the EPA agents investigating the crisis. Prophecy feels a bit ponderous, and painfully a product of its late ’70s origin, but don’t pass it by without appreciating one of the most unintentionally hilarious death scenes in the history of monster cinema. Absolutely worth a click. —Jim Vorel

49. Basket Case (1982)Director: Frank Henenlotter

Bargain bin horror really reached a new level in the 1980s as filmmaking equipment became more widely available. Made for only $33,000, Basket Case nevertheless received a fairly wide theatrical release, proving once again that horror is the genre where opportunity always knocks. Armed with little more than some crappy actors and a big wicker basket, Henenlotter crafted this schlocky tale of two brothers: A seemingly normal guy named Duane and his separated, deformed Siamese twin Belial, who he carries around with him at all times. Little more than a lumpy, fanged head with one random arm, Belial is at times stop-motion animated as he escapes from his basket and runs amok. The film eventually developed enough of a cult for Henenlotter to return and direct two sequels in the early 1990s. Basket Case ultimately combines some of the subversive humor of a Troma film with Henenlotter’s gory streak to make a zero-budget classic. —Jim Vorel

48. Sputnik (2020)Director: Egor Abramenko

The good news is that, three years later, at least one of Alien’s descendants have figured out that borrowing from its forebear makes far more sense than lazily aping Scott, which explains in part why Egor Abramenko’s Sputnik works so well: It’s Alien-esque, because any film about governments and corporations using unsuspecting innocents as vessels for stowing extraterrestrial monsters for either weaponization or monetization can’t help evoke Alien. Abramenko has that energy. Sputnik’s style runs somewhere in the ballpark of unnerving and unflappable: The movie doesn’t flinch, but makes a candid, methodical attempt at making the audience flinch instead, contrasting high-end creature FX against a lo-fi backdrop. Until the alien makes its first appearance slithering forth from the prone Konstantin’s mouth, Sputnik’s set dressing suggests a lost relic from the 1980s. But the sophistication of the creature’s design, a crawling, semi-diaphanous thing that’s coated in layers of sputum equally audible and visible, firmly anchors the film to 2020. Let the new pop cultural dividing line be drawn there. —Andy Crump

47. Werewolves Within (2021)Director: Josh Ruben

With the release of his feature film debut Scare Me last year, director Josh Ruben put himself on the horror-comedy map with his tale about horror writers telling scary stories. With Werewolves Within, Ruben further proves his skills as a director who knows how to walk that delicate line between horror and comedy, deftly moving between genres to create something that isn’t just scary, but genuinely hilarious. The cherry on top? This is a videogame adaptation. Werewolves Within is based on the Ubisoft game of the same name where players try to determine who is the werewolf; Mafia but with shapeshifting lycanthropes. Unlike the game, which takes place in a medieval town, Ruben’s film instead takes place in the present day in the small town of Beaverfield. Forest ranger Finn (Sam Richardson) moves to Beaverfield on assignment after a gas pipeline has been proposed to run through the town. But as the snow starts to fall and the sun sets behind the trees, something big and hairy begins hunting the townsfolk. Trapped in the local bed and breakfast, it’s up to Finn and postal worker Cecily (Milana Vayntrub) to try to find out who is picking people off one by one. But as red herrings fly across the screen like a dolphin show at the local aquarium, it feels almost impossible. Just when you think you’ve guessed the killer, something completely uproots your theories. Writer Mishna Wolff takes the core idea (a hidden werewolf in a small town where everyone knows each other), and places it in an even more outlandish and contemporary context to pack an even funnier punch. While the jokes never stop flowing in Werewolves Within, Ruben and Wolff never lose sight of the film’s horrific aspects through plenty of gore, tense scares and one hell of a climax. This film full of over-the-top characters, ridiculous hijinks and more red herrings than you can keep track of is a great entry in the woefully small werewolf subgenre. —Mary Beth McAndrews

46. Rodan (1956)Director: Ishiro Honda

Fun fact: In Japan, the giant, irradiated pterodactyl we know as Rodan is actually called “Radon,” but the name was changed in the U.S. to avoid confusion with the 86th element of the periodic table. This film, Rodan’s first outing, is significant on multiple levels: It was one of the first kaiju films from Toho to capitalize on the explosion of the genre’s popularity following 1954’s Gojira, and it was the company’s first monster movie in color. Its structure actually feels much more like a modern monster film than you might expect: The crew of a mine shaft are being slowly picked off by mysterious creatures in the darkness, like some twisted version of My Bloody Valentine, before the presence of those insect monsters awakens an even greater threat in the form of the supersonic Rodan. Technically, and in terms of budget, it feels like a significant leap forward from the previous year’s second Godzilla film, Godzilla Raids Again, with production values that set the tone for the next decade of Toho’s kaiju library. —Jim Vorel

45. Creature From the Black Lagoon (1954)Director: Jack Arnold

Like King Kong, this is a horror movie as a love triangle, with both Richard Carlson and the Creature vying for the affections of beautiful, brave, compassionate Julie Adams. Also like King Kong, you’ll find yourself rooting for the monster. Director Jack Arnold portrays the Creature as deeply sympathetic, and the underwater scenes are crisp, even beautiful; rarely are monsters allowed to move so gracefully or act with as much dignity. —Stephen M. Deusner

44. Troll Hunter (2010)Director: André Øvredal

There’s no denying that at its beginning, Troll Hunter seems like another Blair Witch Project knock-off. The first 20 minutes show us a young camera crew investigating some unexplained bear deaths and a suspicious man who may be poaching them. But rather than drawing out the mystery, it takes a sharp turn and tells us matter-of-factly that of course it was trolls killing the bears, and not only that, here’s one of them ready to bonk you on the head. The titular Troll Hunter extraordinaire is played by the affable comedian Otto Jespersen, who brings the entire monster premise to an entirely different level through his nonchalant attitude. In every sense, Troll Hunter lives up to its ridiculous name and premise, while building a surprisingly robust mythology (and featuring far better production design than you’d expect) for the life cycle of its titular trolls. You’ll even come to sympathize with the three-headed monsters before the end. —Sean Gandert

43. The Mist (2007)Director: Frank Darabont

The Mist is straightforward in its high-concept premise, putting its pieces on the table immediately and then allowing the basics of human nature to fill in the cracks. A group of strangers are trapped in a grocery store—that most universal of modern agoras—as an unnatural mist rolls into town, learning quickly that what was only minutes before a parking lot is now filled with blood-hungry giant insects and Lovecraftian monsters. What else is left but for the market’s little society to develop its own quickly crumbling power structures? The film is a microcosm of how human beings adapt and react (or fail to do so) in a crisis, with some electing to strike out on their own and others clinging to any kind of soothsaying that offers comfort, even if it’s the deranged religious dogma of Marvia Gay Harden’s Mrs. Carmody. Our audience proxy, Thomas Jane’s David, is a father who ends up trapped in the market with his young son, ultimately being thrust into leadership positions where he must choose between the wellbeing of his own kid vs. the potential safety of the entire group. With an incredibly bleak ending that diverges significantly from King’s work, the film is ultimately among the most deeply nihilistic adaptations of the author’s work. —Jim Vorel

42. A Quiet Place (2018)Director: John Krasinski

A Quiet Place’s narrative hook is a killer—ingenious, ruthless—and it holds you in its sway for the entirety of this 95-minute thriller. That hook is so clever that, although this is a horror movie, I sometimes laughed as much as I tensed up, just because I admired the sheer pleasure of its execution. The film is set not too far in the future, out somewhere in rural America. Krasinski plays Lee Abbott, a married father of two. (It used to be three.) A Quiet Place introduces its conceit with confidence, letting us piece together the terrible events that have occurred. At some point not too long ago, a vicious pack of aliens invaded Earth. The creatures are savagely violent but sightless, attacking their prey through their superior hearing. And so Lee and his family—including wife Evelyn (Emily Blunt) and children Regan (Millicent Simmonds) and Marcus (Noah Jupe)—have learned that to stay alive they must be completely silent. Speaking largely through sign language, which the family knew already because Regan is deaf, Lee and his clan have adapted to their bleak, terrifying new circumstance, always vigilant to ensure these menacing critters don’t carve them up into little pieces. As you might expect, A Quiet Place finds plenty of opportunities for the Abbotts to make sound—usually accidentally—and then gives the audience a series of shocks as the family tries to outsmart the aliens. As with a lot of post-apocalyptic dramas, Krasinski’s third film as a director derives plenty of jolts from the laying out of its unsettling reality. The introduction of needing to be silent, the discovery of what the aliens look like, and the presentation of the ecosystem that has developed since their arrival is all fascinating, but the risk with such films is that, eventually, we’ll grow accustomed to the conceit and get restless. Krasinski and his writers sidestep the problem not just by keeping A Quiet Place short but by concocting enough variations on “Seriously, don’t make a noise” that we stay sucked into the storytelling. Nothing in his previous work could prepare viewers for the precision of A Quiet Place’s horror. —Tim Grierson

41. Monsters (2010)Director: Gareth Edwards

Monsters is the film that gave the world its first look at director Gareth Edwards, who parlayed its micro-budget success (this movie was less than $500,000) into a chance to direct blockbusters Godzilla and then Rogue One: A Star Wars Story—an incredible leap forward in prominence in the film community. Monsters, on the other hand, is almost like a sci-fi relationship drama, a film about a journalist tasked with escorting a tourist across a dangerous, quarantined zone of Central America that has become home to alien lifeforms. Edwards skillfully makes the most of on-location shooting and very limited FX to evoke a sense of how the aliens are effectively transforming the planet, and of how their arrival changed everything for mankind. Ultimately, though, you’re watching this film for the performances and subtle interplay between its characters rather than any kind of spectacle. Go in looking for a scary movie or action romp, and you’ll be disappointed. You need to take it for what it is: a realistic story about what it might be like for two average people with complicated emotional baggage being thrust into a challenging scenario. Whatever you do, just don’t see the 2014 sequel in name only, Monsters: Dark Continent. —Jim Vorel

40. Attack the Block (2011)Director: Joe Cornish

Written and directed by Joe Cornish, the sci-fi action comedy centers on a gang of teenage thugs—particularly their disgruntled leader, Moses, remarkably underplayed by a young John Boyega—and their housing project in South London. When the defiant juveniles take their crime to a new level and mug an innocent nurse (a delightful Jodie Whittaker), they immediately find themselves plagued by alien invaders. These hideous creatures, with their jet black fur and glowing blue fangs, want nothing more than to destroy the boys and their tower block. In the spirit of Spielberg—even more so than J.J. Abrams’ Spielberg ode of the same year, Super 8—Cornish uses alien beings as the catalyst to bring supernatural redemption to a person and a community. He focuses specifically on London’s socioeconomic bottom half and the turmoil surrounding them, exposing the lies that society’s youth buy into that prolong cultural discontinuity. A comical scene, in which Moses tries to make sense of the aliens while giving excuses for his criminal behavior, highlights this cleverly—he doesn’t just blame the government for violence and drugs in his neighborhood, he blames the government for the whole alien invasion. Cornish, however, doesn’t simply confront this hopeless attitude, he points toward hope—most vividly in the way Moses battles the aliens, his fight rapt with symbolic implications. —Maryann Koopman Kelly

39. 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957)Director: Nathan H. Juran

The history of monster cinema is dotted with the career accomplishments of legendary stop-motion animators like Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen, creators of beasts that both terrified and evoked unexpected sympathy from nickelodeon audiences of their day. Harryhausen took everything he had learned while studying under O’Brien to make style-defining films such as The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, then refined those techniques a few years later for 20 Million Miles to Earth, a film that is something like what E.T. might have looked like if the alien had never met Elliott, and also grew to monstrous size and went on a confused rampage. The Venusian “Ymir” is one of Harryhausen’s most sympathetic creations—not an invader, but a captive of American imperialism that is transplanted to a foreign planet and then demonized for daring to exist and fight back against its tormentors, with obvious parallels to King Kong. As in that film, man’s hubris is ultimately revealed as the true monster, but the popcorn munchers in the audience still get to indulge in some thrills as well. —Jim Vorel

38. Q: The Winged Serpent (1982)Director: Larry Cohen

Q is a decidedly strange monster movie, seemingly the result of filmmaker Larry Cohen wanting to make a throwback creature feature that would remind him of the films of his youth, but simultaneously unable to disentangle the old-school structure of a “monster attacks city” feature from his fascination with the gritty, grimy underbelly of modern city living. We end up, then, with a protagonist who is pure Cohen—small-time grifter Jimmy Quinn (a deadpan Michael Moriarty), who stumbles upon the monster’s lair and then spends the majority of the film trying to extort money from the city in exchange for its location, even as the titular winged serpent is spending the days flying around, killing random New Yorkers. Where other films in the genre would be more concerned with that spectacle, Cohen instead is digging ever deeper into that cynical commentary on our tendency to always look out for #1. —Jim Vorel

37. Little Shop of Horrors (1986)Director: Frank Oz

Rick Moranis shines as nerdy, milquetoast florist Seymour Krelborn, whose Venus Flytrap-esque plant Audrey II requires human blood to survive. The audience sees Krelborn juggle success with his own plant’s insatiable appetite, and we get some big laughs along the way with help from Steve Martin, Bill Murray and The Four Tops’ Levi Stubbs as Audrey II, complete with an array of bombastic musical numbers. Although the idea of a killer plant and some questionable language might raise a few eyebrows, the film’s light-hearted attitude and fantastic musical moments make Little Shop of Horrors a great selection for horror-seeking young people. Compared with the 1960 original from Roger Corman, it’s a far more slick and humor-laden presentation of the same story. —Tyler Kane

36. The Blob (1988)Director: Chuck Russell

Of all the horror remakes of the 1980s, The Blob proved to have perhaps the easiest and most natural of transitions. Simply swap out the communist paranoia of the Steve McQueen-starring 1958 original for some light satirization of the horror genre itself, along with a healthy dose of governmental distrust, and you’re all the way there. It’s remarkable, in fact, just how similar the two films are in terms of structure and characters. Where they diverge, though, is in how they depict Blob-related violence. All Russell’s The Blob has to do is get a bit closer, and the Blob itself does the rest. Incredibly icky sequences of melting faces and severing limbs give certain sequences a Dead Alive sort of flair for comic ultraviolence, but nothing surpasses the phone booth scene, wherein we learn exactly what happens when the full force of the Blob comes crashing down on someone in a confined space. It isn’t pretty. Ultimately, 1988’s The Blob is a solid popcorn thriller that taps into the inherently nostalgic, anti-authoritarian streak also present in the likes of The Return of the Living Dead. —Jim Vorel

35. The Wolf Man (1941)Director: George Waggner

Wolf Man Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.), along with Frankenstein’s Monster, represents the more sympathetic side of the Universal Monster movie canon, although some viewers would doubtlessly use the word “whiny.” Regardless, poor Larry never asked to turn into a werewolf, and he spends most of the sequels trying to figure out a way not only to be cured, but to kill himself and end his long suffering in the process. The 1941 original remains the best and most earnest film in the series—a portrait of a man who has no power over the raging beast within. It’s the film that made Lon Chaney Jr. a household name, throwing him into the same career full of genre films as his father during the silent film era. Famed for the groundbreaking FX of its iconic transformation scene, and aided by the same top-notch makeup that Jack Pierce employed in Frankenstein, it raised the bar for horror FX and makeup substantially. Like other Universal horror films from the classic era of monster horror, it’s heavy on the atmosphere and old-fashioned spooky settings—fog-wreathed graveyards, dark forests and gothic dwellings—while taking to heart some of the lessons learned by superior Frankenstein sequels such as Bride and Son of Frankenstein. Throw it on at your next Halloween party, and you’ll see that it holds up remarkably well. —Jim Vorel

34. Pacific Rim (2013)Director: Guillermo del Toro

With Pacific Rim, Guillermo del Toro has reinvigorated the Kaiju film, one of those rare pulp genres that’s actually native to the silver screen. In doing so, del Toro pulls off an even rarer feat, creating a movie that both distills and perfects the tradition from which it’s drawn. (Del Toro also delivers a few lessons in genre storytelling that many of the top names in sci-fi and fantasy would do well to emulate.) Ultimately, del Toro’s film is less an homage to the Kaiju film than the long overdue perfecting of it using technology that has finally caught up to the genre’s demands. (In this, it shares much with the superhero film efforts of the last decade or so.) Pacific Rim is the Kaiju film Ishiro Honda would have made had he $200 million and the technology of today to spend it on. And regardless of its box office success, it is the standard against which future Kaiju films will be—or in the case of its lackluster sequel, was—judged. —Michael Burgin

33. Cloverfield (2008)Director: Matt Reeves

When Matt Reeves dropped Cloverfield on unsuspecting multiplex audiences in 2008, it quickly became painfully clear that the average viewer wasn’t quite ready to absorb what he was dishing out. Today, the same film would no doubt arrive as a streaming original feature from the likes of Netflix or Amazon, where its genre-redefining camera perspective would be less of a risk. That Cloverfield hit theaters in wide release at all is actually something of a marvel, considering how profoundly different it was in a visual sense from anything that the majority of its viewers had ever seen before. The film is of course on some level a “monster movie,” but it’s one where the primary creature is never the center of the film’s attention, precisely because we spend our time following regular folks who are in no way responsible for or connected to its rampage through New York City. For the film’s entire duration, we see only what they see, cleverly capturing one aspect of the true horror present in disaster situations—the very likely reality that no one present will have any idea what is happening, or any idea of what to do about it. Cloverfield puts its characters into some insane situations, but never breaks the trust it establishes that this is a bystander-eye’s view. No four-star general suddenly shows up to explain what’s going on, or empower our protagonists to take on the creature. No key to the creature’s origin is unearthed. It’s just a shaky-cam tribute to the idea that utter chaos can run rampant in one’s life, and there may be not a damn thing you can do about it. —Jim Vorel

32. Tremors (1990)Director: Ron Underwood

Thirty years after the original hit theaters, the Tremors series refuses to go to its grave, as a sixth installment, Tremors: A Cold Day in Hell, arrived in 2018. Faded from the public consciousness at this point is the Kevin Bacon- and Fred Ward-starring first Tremors, an odd little fusion of monster movie and action comedy that first introduced us to Michael Gross’s “Burt Gummer,” who went on to become the de facto hero of the franchise in subsequent installments, minus one Reba McEntire. Tremors is likely a bit more visceral a film than one may remember, a fairly gory, silly yarn about the giant worms known as Graboids that infest the deserts of Nevada and threaten Ward’s ability to score a date with attractive young seismologists. It effectively transplants the psychology of a Jaws-like creature feature to dry land, wondering what exists just outside of our sight. This is most memorably demonstrated in the sequences wherein our cast is trapped on a series of boulders, the Graboids patrolling the edges: As in films like Night of the Living Dead or Cujo, the film creates claustrophobia by confining its characters to a small island of safety that is rapidly becoming untenable. —Jim Vorel

31. Mothra (1961)Director: Ishir? Honda

Ishir? Honda is of course best known as the director of 1954’s original Gojira, but he might as well be called the godfather of kaiju monster movies in general, given that he also brought us the first appearances of Rodan, Mothra and many others besides. Of those films, Mothra is perhaps the most straightforwardly sympathetic toward its title beast—she (Mothra is always a her) is unequivocally one of the “good guys,” a trait that would only be reinforced through her many appearances throughout the Godzilla film series, typically as an ally to Big G. Sure, she lays waste to the occasional city, but it’s usually in service of (rather messily) righting some kind of wrong, such as the abduction/kidnapping of this film’s pair of pint-sized songstresses. Mothra is a symbol of the natural world fighting back against crass, cynical exploitation by greedy capitalists, making her the protector of indigenous people everywhere. —Jim Vorel

30. King Kong (2005)Director: Peter Jackson

Everything about Peter Jackson’s King Kong screams “passion project,” from the elongated runtime to the way the screenplay eventually turns the giant ape into the de facto protagonist of the film. The success of The Lord of the Rings essentially guaranteed Jackson a blank check, and he spent it in pursuit of an epic retelling of what many consider to be the greatest monster movie of all time. And at its heart, Jackson’s King Kong is a resonant success on an emotional level, with a stellar performance from Andy Serkis in the motion-captured title role, even if the Skull Island segments often seem particularly bloated 15 years later. Still, as a pure creature feature this film is often packed with legitimate nightmare fuel, particularly in the sequence when Carl Denham’s crew is half devoured alive by giant insects—material more genuinely disturbing than Jackson’s own early career horror phase. This King Kong is rife with monster-on-human violence. —Jim Vorel

29. Gremlins (1984)Director: Joe Dante

In the same vein as Die Hard, Joe Dante’s Gremlins is a yearly Christmastime argument waiting to happen: Both are annually tossed onto “best Christmas movie” lists, but when it comes to the latter, at least, those debates often overlook the dark comedy of an expertly crafted ’80s horror film from Dante at the height of his powers. Taking the lessons he learned as a ’70s Roger Corman protege, Dante borrows character actors like Dick Miller to create a cynical, biting rebuke of maudlin sentimentality and children’s entertainment. The film’s surprising counterpoint between comedy and graphic violence was a source of consternation that matriculated it into the early class of genre films that led to the PG-13 rating, but its more important impact was shaping the aesthetic of nearly every horror comedy to come. —Jim Vorel

28. Colossal (2016)Director: Nacho Vigalondo

Colossal is simply a much darker, more serious-minded film than one could possibly go in expecting, judging from the marketing materials and rather misleading trailers. It blooms into a story about sacrifice and martyrdom, while simultaneously featuring an array of largely unlikable characters who are not “good people” in any measurable way. I understand that description sounds at odds with itself—this film is often at odds with itself. But in the cognitive dissonance this creates, it somehow finds a streak of feminist individuality and purpose it couldn’t have even attempted to seek as a straight-up comedy. What Nacho Vigalondo has created in Colossal is a truly unusual, sometimes head-scratching aberration, a film with tonal shifts so jarring that the audience’s definition of its genre is likely to change repeatedly in the course of watching it. Aspects of the film defy explanation, but one thing is clear: Nobody was stifling the writer-director, and we’ve been given one of the most interesting films of 2017. Vigalondo takes aim at the cliches of film festival dramas before smashing them under a giant, monstrous foot. —Jim Vorel

27. Them! (1954)Director: Gordon Douglas

What Gojira was for the birth of the Japanese kaiju genre, the same year’s Them! was for the subsequent boom in atomic-era giant monster movies in the U.S.A. Widely acknowledged as the first of the “giant bug” movies, which would later include such “classics” as Earth vs. The Spider or The Deadly Mantis, Them! taps into the burgeoning existential dread of the early nuclear age, as society came to grasp with the fact that the species now possessed weapons that could effectively end the world overnight. Sure, those fears are manifested here as giant, irradiated ants, but the symbolism isn’t hard to grasp, even more than 60 years later. It’s a classic mishmash of thrills, suspense, paranoia and simultaneous hope for a bright and shiny future, summed up by its ominous closing narration: “When Man entered the Atomic Age, he opened the door to a new world. What we may eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict”. —Jim Vorel

26. Predator (1987)Director: John McTiernan

For all of the jokes and terrible impersonations made over the decades at the expense of Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger, during his peak throughout the ’80s, the actor possessed a certain joie de vivre unmatched by any action performer in Hollywood (with the possible exception of Bruce Willis). Schwarzenegger’s impish charm contrasts beautifully with his larger-than-life, muscle-bound physique, a dynamic he’s always happy to entertain. But Predator is one of the films of his heyday that dared to conjure a threat that even the specter of Schwarzenegger might not be able to conquer, a space-traveling alien trophy hunter who assembles a grisly collection of skulls and spinal columns throughout. It’s a basic premise that was utterly run into the ground by copycat B movies in the years to follow, but none of them come close to replicating the hyper-macho camaraderie that makes Predator an enduringly entertaining relic of its time. The sophomoric banter between the likes of Jesse Ventura, Carl Weathers and Shane Black is what sets the film apart, infusing it with a somehow endearing gentleman’s club mentality, fully aware of its inherent stupidity. We want to see this merry band of special forces operatives conquer the faceless chameleon set against them. There’s wry satire here about America’s attitude toward meddling in the affairs of less-developed nation states, but more than anything, Predator is simply one of the ’80s ’ best games of cat and mouse. —Jim Vorel

25. Monsters Inc. (2001)Director: Pete Docter

Monsters, Inc. may very well be the most lovable film in the illustrious Pixar canon, even if it might feel initially out of place on a list of the best “monster movies.” But given that it literally revolves entirely around monsters, how can you keep it off? Based on everything from the exhilarating door-chase sequence to the brilliant decision of naming its colorful monsters run-of-the-mill things like Mike Wazowski, it might be Pixar’s most inventive, encapsulating the spirit of childhood unlike any other of the company’s singular creations. Billy Crystal and John Goodman make an endearing and iconic odd couple. And that ending? Perfection. —Jeremy Medina

24. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953)Director: Eugène Lourié

The first of special effects titan Ray Harryhausen’s major features, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms was incredibly influential. The first film to ever feature a giant monster directly attributed to the detonation or radiation from an atomic bomb, it set the template for dozens of creature features that would follow in the 1950s, such as Them! or The Deadly Mantis. Like all of Harryhausen’s stop-motion creations, the Rhedosaurus has great personality and an iconic look, captured in seemingly insignificant details of its full-body articulation. The film moves a little bit slower than some of the movies that followed it, but it’s an absolute must-see for any fans of 1950s science fiction, in the same league as better-known films such as The Day the Earth Stood Still or Earth vs. the Flying Saucers. Certainly, without The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, we might never have received Gojira. —Jim Vorel

23. Hellboy (2004)Director: Guillermo del Toro

If you were making a list of comic book film adaptations that truly understood their source material, that accurately capture the tenor of the comic, then you’d have a hard time keeping both Hellboy and Hellboy 2 off the top of the list. Mike Mignola’s epic comic is one of the best sequential graphic stories of the ’90s and 2000s, and leaving its adaptation to the loving hands of Guillermo Del Toro turned out better than fans could have dared hope. Hellboy is by no means an easy story to commit to film, but it benefits hugely by the perfect casting of Ron Perlman in the role he was born to play—the irascible but goodhearted Anung un Rama, the demon “fated” to bring about the end of the world. Naturally, the perpetually stubborn Hellboy has some differing opinions on the nature of free will. What follows is a joyously vivid, fast-paced feature, full of Lovecraftian monsters but none of the author’s pomp and circumstance. Del Toro’s take on Hellboy crackles with the unabashed energy and enthusiasm of an old-time adventure serial—call him a devilish Indiana Jones, with a slightly surlier disposition. —Jim Vorel

22. Dog Soldiers (2003)Director: Neill Marshall

If someone ever asks me to venture an opinion on the best-looking practical effects/full-body werewolf suits used in a feature-length horror film, the choice of Dog Soldiers will be an easy one to make. This isn’t exactly a character-driven tale, a la American Werewolf in London, but instead an action-packed wolf yarn that pits a squad of soldiers against a rampaging family of lycanthropes in the Scottish Highlands. It borrows the basic structure of Night of the Living Dead to do so, having our group of protagonists holed up in a rickety farmhouse that is under siege by a large group of werewolves. As members of the squad are slowly picked off in increasingly grisly ways, the only question is: Who, if anyone, will survive? Dog Soldiers is a stylish (although sometimes a bit dark and hard to see) entry in the genre, with great pieces of action and, as previously mentioned, some really spectacular werewolf designs. I love the odd proportions they give the monsters—humanoid bodies with long, somewhat thin limbs which give the werewolves an imposing height, but heads that are straight-up wolves rather than a mixture of wolf and man. They look utterly alien, and it’s great. —Jim Vorel

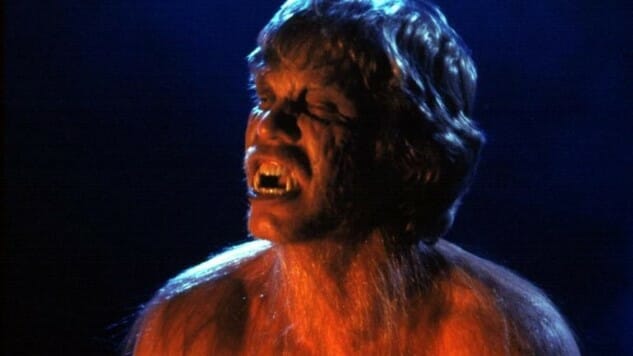

21. The Howling (1981)Director: Joe Dante

1981 happens to be the best year in the history of werewolf cinema, thanks to three films: An American Werewolf in London, The Howling and Wolfen. Of those, The Howling can’t quite compete with the macabre humor and budget of John Landis’ British werewolf classic, but it still ranks among the best lycanthrope movies of all time. The Howling is grittier and darker, but it still maintains a sort of perverted, sadistic sense of humor, as well. Its iconic transformation scenes are long, grisly and exceedingly painful looking, as is just about everything else in this movie, such as the werewolf’s face that has been splashed with corrosive acid—all of the practical effects are absolutely top-notch. It’s rife with historic werewolf movie references for the cinephiles in the audience, including obvious allusions to The Wolf Man and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, while still delivering on the pulp, gore and cheap thrills demanded by the multiplex crowd. That’s the Joe Dante Special: Smart enough to appeal to the film geeks, but silly and funny enough for the layman. It might be the most “pure” of all the modern werewolf films, with a singleminded focus on blood, guts and crowd-pleasing thrills. —Jim Vorel

20. The Monster Squad (1987)Director: Fred Dekker

There’s really only one word for The Monster Squad: “Fun.” For lovers of Halloween, lovers of classic horror, lovers of the Universal monster movies, the film is simply a joy. The mere idea of such a club—a bunch of preteen kids hanging out in a treehouse and devoting their time to Frankenstein and the Wolf-Man—makes me want to step into a de-aging machine so I can put in my application. Sometimes described as being like “The Goonies with monsters,” that’s really not a bad way to sum it up. There’s a colorful energy in the script by Lethal Weapon’s Shane Black, and a definite adult streak that makes this film just as enjoyable today as it was in the late ‘80s. Directed by Fred Dekker, who was also responsible for the much more adult, gory/funny 1986 classic Night of the Creeps, it follows this band of child adventurers as they oppose the evil plans of Dracula and his various monster minions—The Mummy, The Creature from the Black Lagoon, etc, etc. It treads an expert line between adventure, humor and light scares. It’s the perfect Halloween party movie, especially for nostalgic ‘80s and ‘90s kids. —Jim Vorel

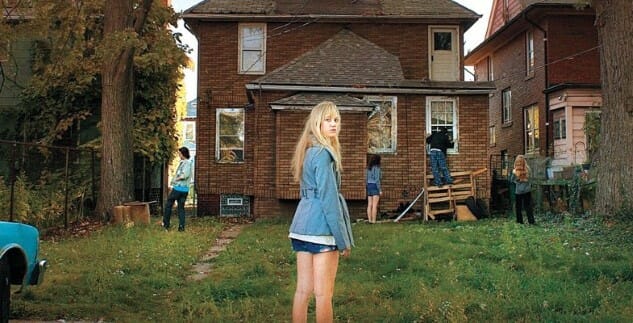

19. It Follows (2014)Director: David Robert Mitchell

The specter of Old Detroit haunts It Follows. In a dilapidating ice cream stand on 12 Mile, in the ’60s-style ranch homes of Ferndale or Berkley, in a game of Parcheesi played by pale teenagers with nasally, nothing accents—if you’ve never been, you’d never recognize the stale, gray nostalgia creeping into every corner of David Robert Mitchell’s terrifying film. But it’s there, and it feels like SE Michigan. The music, the muted but strangely sumptuous color palette, the incessant anachronism: In style alone, Mitchell is an auteur seemingly emerged fully formed from the unhealthy womb of Metro Detroit. Cycles and circles concentrically fill out It Follows, from the particularly insular rules of the film’s horror plot, to the youthful, fleshy roundness of the faces and bodies of this small group of main characters, never letting the audience forget that, in so many ways, these people are still children. In other words, Mitchell is clear about his story: This has happened before, and it will happen again. All of which wouldn’t work were Mitchell less concerned with creating a genuinely unnerving film, but every aesthetic flourish, every fully circular pan is in thrall to breathing morbid life into a single image: someone, anyone slowly separating from the background, from one’s nightmares, and walking toward you, as if Death itself were to appear unannounced next to you in public, ready to steal your breath with little to no aplomb. —Dom Sinacola

18. The Shape of Water (2017)Director: Guillermo del Toro

If there’s a waiting period filmmakers must abide before they can borrow from their own body of work, Guillermo del Toro either doesn’t know or doesn’t care. His latest, The Shape of Water, an ageless story of true love between a human woman and a fish-man, references his filmography both at and below surface levels: It suggests a riff on Abe Sapien, the psychic ichthyoid sidekick in both Hellboy films (who is himself a riff on Creature from the Black Lagoon’s Gill-man, fed through a copyright strainer by his creator, Mike Mignola), but directly invokes the structure and fairy tale trappings of his 2006 breakout picture, Pan’s Labyrinth. Del Toro has us set down in 1960s Baltimore, where Elisa Esposito (Sally Hawkins) works the janitorial night shift for the not-at-all-shady Occam Aerospace Research Center. She’s alone, mostly, except for her next door neighbor, Giles (Richard Jenkins), and her coworker and friend, Zelda (Octavia Spencer). Giles and Zelda give Elisa a voice she quite literally lacks: She’s mute, and spends most of the film communicating with sign language. Elisa’s clockwork days are disrupted by the arrival of the Asset (Doug Jones, the actor behind Abe Sapiens’ prosthetics), the aforementioned fish-man, in the custody of Colonel Strickland (Michael Shannon), at once the epitome of the del Toro villain and the average Shannon role: He’s abusive, violent, dictatorial to a fault, but mannered, the kind of bastard who thinks his dastardly bastard deeds are right and never thinks twice about his own morality. Elisa, ballsier than Strickland and basically every other man in the film, develops instant kinship with the creature. The success of their relationship hinges on performance as much as on direction. Del Toro cares about the well being of freaks and aberrations more than most people care about the well being of other actual people. Visually, The Shape of Water screams dieselpunk, signifying Bioshock more than the brothers Grimm, but the film bears the indelible stamp of folkloric mythmaking all the same. Del Toro weaves together his influences so finely, so delicately, that the product of his handiwork feels entirely new. That’s the magic of the movies, and, more importantly, the magic of del Toro. —Andy Crump

17. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)Director: Terence Fisher

The film that birthed the stylistic idea of “Hammer Horror” and brought back the greatest of the Universal Monsters to the mainstream: It’s Curse of Frankenstein. And it’s difficult to do justice to how important a moment this was for the future course of horror history, the effective launching point of a second Golden Age of serious monster movies. In the ’40s and ’50s, classical horror had been in decline, co-opted by comedies such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein or the burgeoning science fiction genre. It was Curse of Frankenstein and Hammer’s subsequent Dracula and Mummy follow-ups that convinced audiences the old monsters could once again be treated as the stuff of nightmares, and they did so by infusing the old black-and-white specters with opulence, cleavage and pulses of Technicolor blood that brought shock and titillation back to the genre. Unlike the Universal series, the Hammer Frankenstein films make no qualms about the identity of the true villain—it’s the Doctor himself, played with petulant verve by the great Peter Cushing. He morphs into something of an antihero throughout the sequels, but this imperious Frankenstein, who thinks he simply knows better than the foolish, close-minded villagers impeding his work, is the obvious spiritual forebear to Jeffrey Combs’ Herbert West in Re-Animator. Christopher Lee’s monster, on the other hand, is an afflicted creature without the soul or humanity of Karloff’s iconic creation. We fear him, and pity him, but this is Cushing’s time to shine and revel in his own crapulence. —Jim Vorel

16. Shin Godzilla (2016)Director: Hideaki Anno, Shinji Higuchi

In the shadow of Shin Godzilla, Hollywood has failed. Gareth Edwards’ 2014 Godzilla movie wasn’t really one so much as it was a brand exercise, astoundingly executed, but divorced from Toho’s legendary lizard flicks. Godzilla (2014) does not encourage audiences to seek out Godzilla (1954), because the two are fundamentally different beasts, the former adept at creating some serious awe and suspense from its abundant CGI, while the latter wore its allegorical bonafides openly, strikingly realized man-in-rubber-suit mise-en-scene providing a stark balance to images of evacuating citizens, panicking under the threat of otherworldly disaster having just gotten over a previous otherworldly disaster. Hollywood doesn’t know what to do with that kind of trauma.

Looking back, Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi seem to have preemptively rescued what Hollywood would have otherwise lost. Rendering the CGI Godzilla with traces of rubber-suit bounce and flavor, they never abandon the tactile nature of the kaiju melee to the endless void of photorealism, while still reinventing, from one moment to the next, what Godzilla, and Godzilla, is. Like Ishiro Honda’s first Godzilla, Shin Godzilla is about the threat of nuclear annihilation as much as it is about Japan’s ability to band together—which isn’t so much a virtue as it is a survival mechanism—in this case alluding directly to the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. It’s also half dry political farce, starring the facile entirety of the Japanese government, that tumbles into a sci-fi thriller that almost trips into rom-com, metamorphosing and evolving, as does its monster, into ever delightful permutations of the kaiju formula. At one point, Godzilla splits the bottom of its jaw apart to open its gaping maw even wider, hemorrhaging nuclear energy like so much projectile vomit. It means nothing, and it means everything, and it means that some poor bureaucrat’s got a lot of paperwork to do. —Dom Sinacola

15. Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)Director: Guillermo del Toro

One of the most imaginative films of the 21st century, Guillermo del Toro’s dark Spanish fable is a triumph of storytelling and nothing short of a work of art. Simultaneously a war saga and a fairy tale, it traces the journey of a young girl and her scavenger hunt through another world to save her mother’s life, set in the midst of the Spanish civil war. Pan’s Labyrinth oozes atmosphere with its stunning cinematography and production values, all guided by del Toro’s keen artistic vision. With this out-and-out masterpiece, del Toro cemented his position as one of this generation’s most exciting and talented visionaries, even as he explored some of his favorite territory, replete with monsters and magic. —Jeremy Medina

14. Young Frankenstein (1974)Director: Mel Brooks

One of the best comedies of all time and one of the 10 or so films I can quote almost entirely from memory, Young Frankenstein is a classic of the genre. At once a spoof of traditional Universal horror films and a loving tribute, with a surprising number of deep references to Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein in particular, Mel Brooks and his immensely talented cast have created a timeless film. It follows Dr. Frederick Frankenstein (played by Gene Wilder) as he finally gives into continuing his grandfather’s (the Frankenstein) experiments. A classic for all ages, Peter Boyle’s take on Frankenstein’s monster is more playful than scary—after all, it’s hard to see a kid being terrified by a tap-dancing monster, even if he is “puttin’ on the ritz.” —Mark Rabinowitz

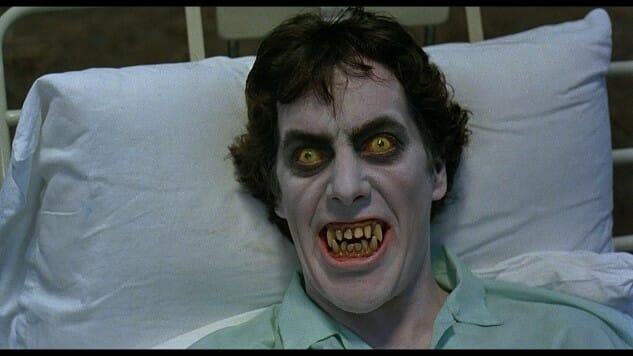

13. An American Werewolf in London (1981)Director: John Landis

Few directors have ever displayed such an innate tact for combining dark humor and horror the way John Landis does. At the height of his powers in the early ’80s, one year removed from The Blues Brothers, Landis opted for a much grittier, scarier story that stands as what is still the best werewolf movie of all time. When two travelers backpacking across the English moors are attacked by a werewolf, one is killed and the other, David (David Naughton), infected with the wolf’s curse. Haunted by the simultaneously unnerving and hilarious visions of his dead friend, David must decide how to come to terms with the monster he has become, even as he strikes up a relationship with a beautiful nurse (Jenny Agutter). The film lulls you into comfort with its witticism before springing shocking, gory dream sequences on the viewer, which repeatedly arrive unannounced. The key moment is the protagonist’s incredibly painful, traumatic full transformation, set to the crooning of Sam Cooke doing “Blue Moon,” which is still unsurpassed in the history of the genre. Legendary FX and monster makeup artist Rick Baker took home the first-ever Academy Award for Best Makeup and Hairstyling for creating a scene that has given the wolf-averse nightmares ever since. —Jim Vorel

12. Frankenstein (1931)Director: James Whale

Though Dracula might be more famous, the crown jewel of Universal’s golden age of monster movies was always Frankenstein. Technically superior, and with the benefit of more lively, engaging direction from James Whale, who seems a bit more comfortable working in the sound medium, Frankenstein is an unchallenged masterpiece, albeit one that is perhaps surpassed several times by its first two sequels. Its heart is of course the all-time great performance from Boris Karloff as “the monster,” perhaps the first time that many audiences had seen such a role swimming in obvious pathos for a creature designated in the collective imagination as the film’s “villain.” Unlike sequels Bride of Frankenstein or Son of Frankenstein, one can say that there really is no true antagonist to the first film—the monster is a pitiable figure lashing out against a world that instinctively condemns him the moment they lay eyes on him. Rather, it’s humanity’s own failings—both our hubris and our lack of empathy—that are highlighted. Thematically, it made for much richer horror fodder than many of the lesser monster films that would follow. —Jim Vorel

11. Aliens (1986)Director: James Cameron

James Cameron colonizes ideas: Every beautiful, breathtaking spectacle he assembles works as a pointillist representation of the genres he inhabits—sci-fi, horror, adventure, thriller—its many wonderful pieces and details of worldbuilding swarming, combining to grow exponentially, to inevitably overshadow the lack at its heart, the doubt that maybe all of this great movie-making is hiding a dearth of substance at the core of the stories Cameron tells. An early example of this pilgrim’s privilege is Cameron’s sequel to Ridley Scott’s roughly-feminist horror masterpiece, in which Cameron mostly jettisons Scott’s figurative (and uncomfortably intimate) interrogation of masculine violence to transmute that urge into the bureaucracy and corporatism which only served as a shadow of authoritarianism—and therefore a spectre of the male imperative—in the first film. Cameron blows out Scott’s world, but also neuters it, never quite connecting the lines from the aggression of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation to the maleness of the military industrial complex, but never condoning that maleness, or that complex, either. Ripley’s (Sigourney Weaver) story about what happened on the Nostromo in the first film is doubted because she’s a woman, sure, but mostly because the story spells disaster for the corporation’s nefarious plans. Private Vasquez’s (Jennette Goldstein) place in the Colonial Marine unit sent to LV-426 to investigate the wiping out of a human colony is taunted, but never outright doubted, her strength compared to her peers pretty obvious from the start. Instead, in transforming Ripley into a full-on action hero/mother figure—whose final boss battle involves protecting her ersatz daughter from the horror of another mother figure—Cameron isn’t messing with themes of violation or the role of women in an economic hierarchy, he’s placing women by default at the forefront of mankind’s future war either for or against the ineffable forces of capitalism. It’s magnificent blockbuster filmmaking, and one of the first films to redefine what a franchise can be within the confines of a new director’s voice and vision, but below all of the wonderful genre-based imagination and splendor, Cameron doesn’t have much of anything to say. Still, it’s an awesome film despite itself, a tense action bonanza, and a pretty good reminder all these years and proposed Avatar sequels later that Cameron’s clearly decided on which side of the war he’s fighting. —Dom Sinacola

10. The Host (2006)Director: Bong Joon-ho

Before he was breaking out internationally with a tight action film like Snowpiercer, and eventually winning a handful of Oscars for Parasite, this South Korean monster movie was Bong Joon-ho’s big work and calling card. Astoundingly successful at the box office in his home country, it straddles several genre lines between sci-fi, family drama and horror, but there’s plenty of scary stuff with the monster menacing little kids in particular. Props to the designers on one of the more unique movie monsters of the last few decades—the mutated creature in this film looks sort of like a giant tadpole with teeth and legs, which is way more awesome in practice than it sounds. The real heart of the film is a superb performance by Song Kang-ho (also in Snowpiercer and Parasite) as a seemingly slow-witted father trying to hold his family together during the disaster. That’s a pretty common role to be playing in a horror film, but the performances and family dynamic in general truly are the key factor that help elevate The Host far above most of its ilk. —Jim Vorel

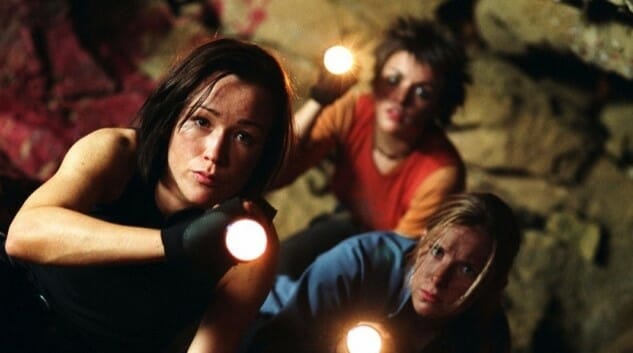

9. The Descent (2005)Director: Neil Marshall

True camaraderie or complex relationships between female characters isn’t so much “rare” in horror cinema as it is functionally nonexistent, which is one of the things that still makes The Descent, nominally about a bunch of women fighting monsters in a cave, stand out so sharply, 12 years after it arrived. But ah, how The Descent transcends its one-sentence synopsis. The film’s first half is deliberately crafted to fill in the personalities of the women, while slowly and almost imperceptibly ratcheting up the sense of dread and foreboding. As the women descend deeper into the cave, passageways get tighter and the audience themselves can feel the claustrophobia and dankness creeping into their bones—and that’s before we even see any of the resident troglodytes. Neill Marshall’s screenplay makes masterful use of dubious morality, infusing its protagonists, particularly the duo of Sarah (Shauna Macdonald) and Juno (Natalie Mendoza), with numerous shades of gray. Not content to simply paint one of the two as flawed and the other as resourceful and ultimately vindicated, he uses a series of misunderstandings to illustrate human failing on a much more profound and universal level. Ultimately, The Descent is as moving a character study as it is terrifying subterranean creature feature, with one hell of an ending to boot. —Jim Vorel

8. Jurassic Park (1993)Director: Steven Spielberg

Jurassic Park, in 1993, was an achievement in major league filmmaking. Like Star Wars before it, it showcased a quantum leap in visual effects—both physical and CGI, in this case. Most important, however, were those CGI advancements. Jurassic Park, for better or worse, probably represents the first moment in our modern AAA Hollywood mythos in which an audience could look at CGI-driven creatures, nod their heads and simply accept them as part of the story. Married with one of the greatest pure adventure yarns in Spielberg’s celebrated canon, Jurassic Park was the spectacle we’ve come to expect of the traditional “blockbuster.” That loose term, since the days of Jaws, has always referred to a breed of films that are supposed to succeed by wowing us and making jaws drop. Jurassic Park did that in a way that infinitely raised expectations for every effects-driven money-maker thereafter. —Jim Vorel

7. Gojira (1954)Director: Ishiro Honda

Early in Godzilla, before the monster is even glimpsed off the shore of the island of Odo, a local fisherman tells reporter Hagiwara (Sachio Sakai) about the play they’re watching, describing it as the last remaining vestige of the ancient “exorcism” his people once practiced, sacrificing a young girl to the calamitous sea creature to satiate its hunger and cajole it into leaving some fish for the people to enjoy, at least until the next sacrifice. Ishiro Hondo’s smash hit monster movie—the first of its kind in Japan, the most expensive movie ever made in the country at the time, not even a decade after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—is, after 20-something sequels over three times as many years, a surprisingly elegiac exorcism of its own, a reminder of one nation’s continuing trauma during a time when the rest of the world jonesed to forget. As J Hoberman describes in his essay for the film’s Criterion release, much of Honda’s disaster imagery is “coded in naturalism,” a verite-like glimpse of the harrowing destruction wrought by the beast but indistinguishable from the aftermath of the Americans’ attacks in 1945, especially when the U.S. and Russia, among other powers, were testing H-bombs in the Pacific in the early 1950s, bathing the Japanese in even more radiation than that in which they’d already been saturated. And yet, Godzilla is a sci-fi flick, replete with a “mad” scientist in an eye patch and a human in a rubber dinosaur suit flipping over model bridges. That Honda handles such goofiness with an unrelentingly poetic hand, purging his nation’s psychological grief in broadly intimate volleys, is nothing short of astounding. Shots of Godzilla trudging through thick smoke, spotlights highlighting his gaping maw as the Japanese military’s weapons do nothing but shock the dark with beautiful chiaroscuro, have been rarely matched in films of its ilk (and in the director’s own legion of sequels); Honda saw gods and monsters and, with the world entering a new age of technological doom, found no difference between the two. —Dom Sinacola

6. Bride of Frankenstein (1935)Director: James Whale

We’re happy to go to bat for Son of Frankenstein as well, but thankfully that’s not so necessary with Bride, which is already widely regarded as superior to Whale’s own 1931 original. Colin Clive returns as the Doctor in this first sequel, now haunted by the destruction his creation has wrought. He would happily wash his hands of the incident, but for the interjection of an old colleague, Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), who seduces Frankenstein back into additional morbid business by revealing to him his own macabre discoveries. The monster, meanwhile, has survived its near immolation in the conclusion of the first film, and experiences unexpected character development—first bonding with an old hermit in the woods, before being unfortunately discovered by the ambitious Pretorius, who teaches him to speak and turns him against his idealistic (but deluded) creator. It’s Boris Karloff’s finest hour, as he imbues the tragic monster with not only sorrow but righteous anger and a deep yearning for acceptance and anonymity that he believes he can find in the titular “Bride.” The film is a gothic masterpiece of old-school, lightly campy spooks, swinging ably from broad humor to impressionistic fright, to the Poe-esque crypts where Pretorius sets up shop. Ernest Thesiger, utterly steals the show by truly bringing the “mad” into “mad scientist.” His initial meeting and salutation to the Monster, sitting comfortably among the skulls of a mass grave without a hint of fear, may be the most iconic horror scene of the ’30s. —Jim Vorel

5. The Fly (1986)Director: David Cronenberg

Between The Blob, The Thing and The Fly, the ’80s were a magical decade for remaking already iconic ’50s horror/sci-fi movies. The original Kurt Neumann/Vincent Price version of The Fly is sometimes waved away as nothing more than a “camp classic,” but it’s a substantial film that is often more mystery than it is horror—a tightly focused narrative hinging around the question of why a woman has confessed to messily crushing her husband to death in a hydraulic press. Vincent Price is as entertaining as the fly-crossed scientist as you would no doubt expect him to be. The Cronenberg version, like the remake of The Blob, takes that basic premise and dresses it in both gallows humor and body horror, as Jeff Goldblum’s researcher literally watches pieces of his body gelatinize and melt away in front of him. As “Brundle” he’s great, full of manic energy, ingenuity and eventually insectoid-enhanced physicality. Along with The Thing, the film is one of the last great hurrahs of the practical effects-driven horror era, featuring some of the more disgusting makeup and gore effects of all time. After seeing a man-sized Brundlefly vomiting acid, it’s difficult to ever look at a common housefly in the same way again. —Jim Vorel

4. Jaws (1975)Director: Steven Spielberg

Because someone is sure to ask: Is Jaws a monster movie? For those who worry that it’s “not safe to go back in the water,” then most certainly it is. But regardless of how you’d classify it, there’s no denying that Jaws is anything but brilliant, one of Spielberg’s great populist triumphs, alongside the likes of Jurassic Park and E.T., but leaner and less polished-looking than either, which actually works in its favor. Much has been made over the years of how Jaws as a film really benefits from the technical issues that plagued its making—the story originally called for more scenes featuring the mechanical shark “Bruce,” but the constantly malfunctioning animatronic forced the director to cut back, which ended up maximizing each appearance’s impact. The first time that Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) sees the literal “jaws” of the beast while absentmindedly throwing chum into the water is one of the great, scream-inducing moments in cinema history, and it’s a shock that has literally never been matched in any other shark movie since. Likewise with the death of Quint (Robert Shaw), whose mad scramble to avoid those gnashing teeth is the kind of thing that created its very own sub-genre of children’s nightmares. Ultimately, Jaws is made into a great film via memorable characters, but it’s made into a scary film by novelty and perfect execution. —Jim Vorel

3. Alien (1979)Director: Ridley Scott

Conduits, canals and cloaca—Ridley Scott’s ode to claustrophobia leaves little room to breathe, cramming its blue collar archetypes through spaces much too small to sustain any sort of sanity, and much too unforgiving to survive. That Alien can also make Space—capital “S”—in its vastness feel as suffocating as a coffin is a testament to Scott’s control as a director (arguably absent from much of his work to follow, including his insistence on ballooning the mythos of this first near-perfect film), as well as to the purity of horror as a cinematic genre. Alien, after all, is tension as narrative, violation as a matter of fact: When the crew of the mining spaceship Nostromo is prematurely awakened from cryogenic sleep to attend to a distress call from a seemingly lifeless planetoid, there is no doubt the small cadre of working class grunts and their posh Science Officer Ash (Ian Holm) will discover nothing but mounting, otherworldly doom. Things obviously, iconically, go wrong from there, and as the crew understands both what they’ve brought onto their ship and what their fellow crew members are made of—in one case, literally—a hero emerges from the catastrophe: Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), the Platonic ideal of the Final Girl who must battle a viscous, phallic grotesque (care of the master of the phallically grotesque, H.R. Giger) and a fellow crew member who’s basically a walking vessel for an upsetting amount of seminal fluid. As Ripley crawls through the ship’s steel organs, between dreams—the film begins with the crew wakening, and ends with a return to sleep—Alien evolves into a psychosexual nightmare, an indictment of the inherently masculine act of colonization and a symbolic treatise on the trauma of assault. In Space, no one can hear you scream—because no one is listening. —Dom Sinacola

2. King Kong (1933)Directors: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack

There had been monster movies or “creature features” before Kong, but it became the key reference point for that entire film demographic from the time of its release until the genre underwent an atomic-age reimagining with the likes of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in 1953 and Them! in 1954. Likewise, it set the bar on its special effects at such a high level that in many instances, shots and sequences from King Kong weren’t suitably duplicated for decades to come. Much of the credit belongs to pioneering stop-motion animator Willis O’Brien, who was inventing new techniques on the set of Kong on a daily basis, laying a foundation for an entire field of visual effects that are still being refined by studios such as Laika (the makers of Coraline and Kubo and the Two Strings) today. Those techniques were likewise carried on and further refined by O’Brien’s arguably more famous protege, Ray Harryhausen, who used them to great effect in the second golden age of the monster movie, throughout the 1950s-1970s.

Kong, though, still stands as an unparalleled achievement for its time period—far grander and more ambitious in scope than most anything you can compare it to in the same time frame. On one hand it’s a rollicking adventure film, with a classic “journey into the unknown” plot that is still being recycled for modern monster installments like Kong: Skull Island. At the same time, though, it was likewise an interesting experiment in genre-blending—an FX-driven adventure-drama film with horror elements and no clear-cut, traditional “antagonist.” Carl Denham might fit the bill, but he’s better described as a naive dreamer with stars in his eyes, oblivious to the ethical quandary of shanghaiing a huge beast to display in the middle of New York City. Kong, meanwhile, is a misunderstood creature, operating on the sense of self preservation he learned in a home where he’s only ever known a daily fight for survival against a neverending stream of monsters. The film’s empathy for Kong, and its condemnation of the hubris that led to his ascent of the Empire State Building, are what helped make the story such an emotionally affecting classic. —Jim Vorel

1. The Thing (1982)Director: John Carpenter

No disrespect to the classic Christian Nyby/Howard Hawks version of The Thing From Another World from 1951, but John Carpenter’s 1982 reimagining of that story into The Thing is one of cinema’s greatest acts of modernization. In a manner that was mimicked six years later by the remake of The Blob, Carpenter took a thinly veiled Cold War allegory and cloaked it in his taut, atmospheric style, ratcheting up both suspense and the lurid payoff delivered by groundbreaking FX work, while expanding the mythology and capabilities of the titular monster. Every frame is a visual puzzle, as Carpenter’s camera drifts over empty hallways, open door frames and cloaked figures in the arctic air. Who is The Thing, and more contentiously, when and how did they become The Thing? The theories spiral endlessly into dark corners of the internet, as Carpenter’s visual clues and Bill Lancaster’s script seem to provide the audience with most—but never quite all—of the information they need to be certain. Rob Bottin delivers what may be the literal zenith of practical effects in the history of horror cinema during The Thing’s several transformation scenes, and particularly in the mind-blowing sequence featuring the severed head of Norris (Charles Hallahan) sprouting legs to become a crab-like creature, which attempts to scuttle away. The Thing has become an artifact of big-budget ’80s horror purity: Next-level special effects, a mind-expanding mystery, masterful direction and the awesomeness that is Kurt Russell/R.J. MacReady as the cherry on top. —Jim Vorel

Jim Vorel is a Paste staff writer and resident horror geek. You can follow him on Twitter for more film writing.