Between the Sun, the Sky and Tinder: Nadav Lapid Talks Ahed’s Knee

Photo by Kate Green/Getty Images Movies Features

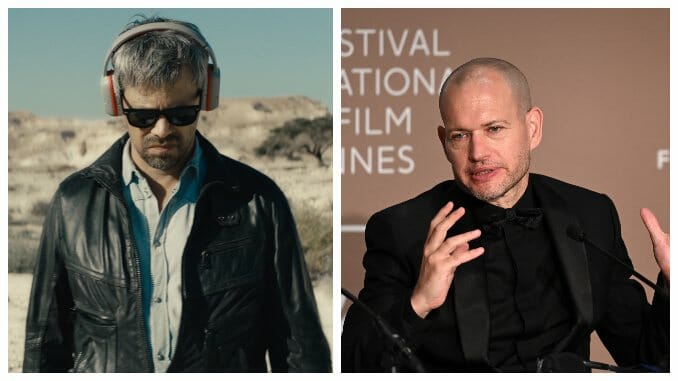

Four features into his career, Israeli filmmaker Nadav Lapid found himself in the Cannes Official Selection for the first time. The writer and director behind 2011’s Policeman, 2014’s The Kindergarten Teacher (later remade in English with Maggie Gyllenhaal) and 2019’s Synonyms was a near shoo-in for the 2021 competition, where he would go on to collect a Jury Prize for his newest, Ahed’s Knee.

In some sense, it feels very much like a film by Lapid, whose career has been defined by searing sociopolitical commentary on the Israeli government, a feverish intensity and a complexity of conflict that feels infinite. But, in another sense, Ahed’s Knee is a departure for Lapid—a new chapter. He wrote the feature in two weeks, and it usually takes him a year or more to finish a screenplay. He explores new filmmaking styles with a stream-of-consciousness sensibility. Most significantly, it marks his first feature without his mother and longtime editor, Era Lapid, who he lost to cancer in June 2018.

It’s also largely autobiographical. The metanarrative follows a celebrated director—Y (Avshalom Pollak), a filmmaker who loves his mother and is hyper-critical of the government’s institutions, especially the ministry of art—to a screening of one of his films in a small town in the Israeli desert, where he’s supposed to give a talk sanctioned by the state. Based on an experience Lapid had while promoting Synonyms, the story is a dizzying, inventive series of thought exercises and spiraling diatribes that wrestles with art, war, politics, truth, intellect and existence in a way only cinema, and perhaps Lapid, can.

As the film is finally out to rent on all major platforms, Paste sat down to talk with him about it.

Paste: You wrote this in two weeks, had a relatively short development and pre-production period, and shot it in 18 days. What was it like flying through the process like that?

Nadav Lapid: I guess it was something between a feeling of deep urgency and deep liberty. And, in a way for me, the only thing that justified the existence of this movie was to be able to fully express a kind of mood, a kind of melody, a kind of music that I felt at a certain moment. Words, of course, all sorts of events and certain situations. This vibrant despair, or this restless sadness. You can call it all sorts of names because it has all sorts of names and all sorts of colors. But, in a way, I felt all these feelings, all these emotions in such a clear way that I had to do this movie while they were still existing. For me, there would have been no interest in doing this movie if I was trying to ask myself, “How was it back then when I wrote the script? Or when something led me to write the script?” And I was really, in a way, led by these feelings, because it’s not only that everything took place really quickly, but I think that the day before I started writing the script, I didn’t know I was going to do this movie. I didn’t have any plan to do it, and I had another project in my head, and less than three weeks we’d already started casting and pre-production. So I had to preserve this feeling of being taken by something, and since it was so powerful, these feelings and emotions, they gave me all the answers I needed, you know? I mean, I knew how to shoot it. I knew from each angle, with which camera movement and with which rhythm.

In making movies, especially fiction movies, we always take so much time, and usually this time is positive. It makes it a well-conceived, well-thought, well-calculated piece of art. And before I made the movie, I remember I was looking at these famous videos of Jackson Pollock, you know, like, running and hitting. So, I wanted to be like Jackson Pollock or the expressionist painters, not like Stanley Kubrick who works for eight years on a movie, you know?

There are so many different styles of filmmaking expressed. Like, the camera whirring with the man snacking in the car, or the sleek, explosive opening sequence that acts as a vessel into the audition, or the desert dance montage. Were those shots in your head when you were writing? And did you write style into the screenplay or primarily figure things out creatively on set?

Lapid: I wouldn’t say that I knew exactly, when I was writing, how each scene would be shot. But I felt the eclectic side of the movie. I felt that while the first scene might look like it’s at the beginning of the new James Bond film, you know, with the, um…

The motorcycle sequence?

Lapid: Yeah, exactly, the motorcycle. If James Bond is a black woman, riding like a storm on a motorcycle. And right after, it turns to be—almost like in this casting [sequence]—kind of artificial, theatrical, political stuff, a little bit like Fassbinder or something like this. And a few seconds later someone is singing “Welcome to the Jungle” by Guns N’ Roses and beating his own knee. And only then, in a way, the movie really begins. Only then, we really meet the main character. Why?

So, I was at war with the fact that there is a kind of, um, well we move from very existential stuff—like the sky, etc.—to YouTube videos. I felt that there was a kind of richness. After, I think this chaotic richness, it was also connected to my mood. But in a way, I felt that it was also a reflection of the truth of that moment. I mean, when you climb the Himalayas and at the same time you’re having a correspondence on WhatsApp with a friend. So you’re exactly there: Between the sun, the sky and Tinder. I felt that there was something in this chaotic richness that was, in a way, expressing the truth of the moment.

I read you describe the movie as taking an “existential aesthetical” position, opposed to a political one, yet it’s a film that’s heavy on political discourse and pretty in your face about it. Can you explain what you meant by that?

Lapid: I feel like in general my movies—and maybe even more this one, which is apparently a very explicit one—first of all, they are different from what we used to call political cinema, at least, you know, the usual political cinema. Because usually in political movies, what happens is you feel very well that the aim of the movie is to promote one opinion or one position or one idea, or on the other hand, to oppose a state of things, condemning them as unjust or something like this. And then, in order to do it, you create a kind of microcosm of cinema, a kind of small local story which serves as a fable to understand. In a way, my movies are totally the opposite.

The movie doesn’t promote any position. In a very simple way, if my main idea would’ve been to protest against censorship, for instance, or to talk mainly—I’m not saying it doesn’t exist, I think the movie has a kind of richness and it also exists—but if the aim of the movie would’ve been to talk about liberty of speech in a clear way, the movie would have had to be clear, because otherwise you don’t reach your aim. And being clear, for instance, I guess would have also been to transform this main character of the director into a kind of heroic character who’s fighting against the system, and the state, which is powerful and cruel, and he has a good heart. Which is, of course, not at all the movie.

I think the movie describes a kind of general sickness, a general disease. And as we know, no one is protected and everyone, in a way, is touched. The woman he’s quoting, his mother, says, “There are no survivors here.” So there are no survivors from these diseases, including himself. And that’s why, you know, he’s pretty terrible. And also, the movie is not the kind of clear moral dilemma where the spectator is supposed to say, “Okay, I would’ve acted like this, or like this.” It’s totally not a question. I think this movie ends, strangely enough—because it’s full of sorrow and bitterness—it ends with a kind of humanistic gesture. But it doesn’t mean that the answer to the problem is being simple and human. It ends with a moment that is a kind of counterweight for everything that we saw before. But I think it’s more about taking the head of the spectator and sticking it in the geography of this actual moment in time as I see it.

And the other thing is that the movie is full of all sorts of ingredients, and colors, and melodies that, as you say, are so different. I mean, the movie is bitter, the movie’s harsh, but when we look at the list of songs, for instance, in the movie, we see Vanessa Paradis and “Lovely Day.” So that’s why I’m saying that it’s more about carols of reality, and inside the carols of reality, politics has an important place, but also dances have an important place, and also the body has an important place, and also sex has an important place, and they are all mixed together. The film is full of politics, but it doesn’t mean the film has a political idea. Much more than he talks about liberty of speech, he talks about goodness: What does it mean to be good? Which is not a straight political question. In the movie, there is, you know, this clear narrative political turning point. But, in a way, I think the characters are already charged with the same explosive charge before the specific event takes place. It only accelerates them and gives them a platform to speak their essence.

How did you start the process of finding another editor and what was it like working with a new editor after you lost your mom?

Lapid: First of all, of course, it wasn’t an easy process. [Pauses] In film school, for instance, I was editing my own movies, so actually I never worked with an editor. But I looked around, like I checked Israeli movies that I liked. I mean, it was critical for me that it should be an Israeli editor because of the Hebrew, and then I looked for Israeli movies I liked, and that’s how I found this editor, Nili Feller.

But in a way, it’s the same on a professional level because I was always extremely involved in the editing. You know, making films is, of course, like many other things—like writing reviews—but it’s also a reflection of life. And I think it’s a little bit like when your parents or one of your parents die, so you feel in a way that you find yourself in the front, on the frontlines of life. So it’s a bit the same here. In a way, the responsibility that I should take is even bigger.

Luke Hicks is a New York City film journalist and arts enthusiast by way of Austin, TX. He got his master’s studying film philosophy and ethics at Duke and thinks every occasion should include one of the following: whiskey, coffee, gin, tea, beer, or olives. Love or lambast him on Twitter @lou_kicks.