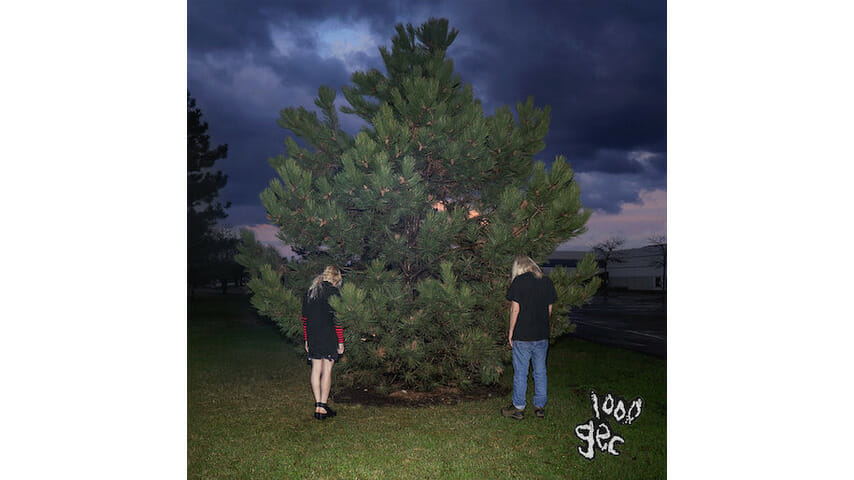

No Album Left Behind: 100 gecs’ 1000 gecs

On their debut, 100 gecs stumbles upon the human condition of being alive, online and listening in 2019

Music Reviews 100 gecs

Over the course of 2019, Paste has reviewed about 300 albums. Yet, hundreds—if not thousands—of albums have slipped through the cracks. This December, we’re delighted to launch a new series called No Album Left Behind, in which our core team of critics reviews some of their favorite records we may have missed the first time around, looking back at some of the best overlooked releases of 2019.

The cross-continental duo of 100 gecs, comprised of Laura Les and Dylan Brady, are pretty astute disciples of the sounds that they love, and seemingly fervent supporters of the idea of obliterating the last boundaries of taste that have lingered in the last decade or so. The gecs’ homage, debut album 1000 gecs, turns an entire digital library of Very Online Music into a collision course to demolish and reconstruct, resulting in a dizzying, hedonic 23 minutes.

Musically, it’s a clusterfuck, a clash of tranced-out Europop, the finest scene music MySpace had to offer in ’06, Skrillex and Diplo’s mainlined EDM collaboration Jack Ü, the hyperreality of PC Music, Dance Dance Revolution soundtracks and more than a smidgen of ska and 2010s rap compressed into an unwieldy repository of noise. It’s a Rorschach test of musical references with new ink being dribbled onto the page, second-by-second, where its interpretation is mutable and entirely dependent on which corners of the internet you lurked on.

Tucked underneath is a collection of lyrics that scan like a strange, almost voyeuristic selection of someone’s private Twitter account, each line spilling out like an archive of tired, stoned and solitary dispatches. Some, like the opening verse of “money machine,” are instant meme fodder, digital taunts that are as funny as the guy who ate baked beans in the theater and lived to tell the tale.

More often than not, like the rest of “money machine” or “800db cloud,” the memes and the weed are all in the service of compartmentalizing the constant loneliness of being anxious and depressed and online. A minute of “sounds of the studio”-esque music software fuckery on “gecgecgec” gives way to an AutoTuned Les confessing to her partner that “I’m not stronger / Stronger than you,” like if Kanye’s “Runaway” was compressed into a 64 kilobyte MP3 blasting out of a Razr. And on “ringtone,” easily the most straightforward song on 1000 gecs, Les coos about the ceaseless stream of notifications on her phone, which are only drowned out by the special ringtone she’s set for her boy—and the gut punch of hearing it in the relationship’s post-mortem.

“I think it’s a comment on our own social media behaviors more so than trying to be some big social commentary,” Dylan Brady told The Outline about the contents of 1000 gecs. That’s fair—no one ever intends to make an album that pinpoints a generation’s neuroses. But this record, with its chaotic bricolage of sounds and aesthetics for the very online, feels like the warped mush of logging on in the year of our lord 2019 and having to parse out a new meme everyday, figuring out the main character on Twitter on any given day—while dealing with whatever fresh political hell is wrought upon us—and finding the rare pockets of pleasure among all of the piss and detritus in the scrolling.

Like the duos of Sleigh Bells and The Postal Service before them, 100 gecs may very well end up as more generational reference point than artist, a touchstone not just of what music sounded like, but what the act of discovering and consuming music felt like at the time.

I can’t help but feel bummed about how the listening habits I established in the halcyon Web 2.0 a decade ago have all been eschewed for the vast beyond of Spotify. The hours spent looking for a Mediafire .zip file, of downloading a hand-curated “indie rock” playlist once a month or of finding a long-forgotten remix on Tumblr—it all felt like crate digging with clicks.

Maybe it was the triumph of discovery, or maybe it was just the music, but the sounds of the early 2010s—the punishing guitar stabs that kick off “Infinity Guitars,” the rule-breaking pleasure of hearing Beach House on a Weeknd joint in 2011 (or on good kid, m.A.A.d. city a year later), the whiplash-inducing splatter of Sophie’s “BIPP”—each felt like a wrecking ball to whatever hang-ups I had about genre limitations and impositions about taste and “indie” and whatever. As a young listener at the time, it was both reorienting and refreshing.

That feeling, in the age of Spotify and algorithms, has mostly vanished as the rubble of culture collapse has largely been bulldozed away for post-post-everything. It could very well be good — as new generations obtain unlimited access to music, they can find, curate and appreciate music on their own terms. But the likelier possibility may very well be that music pivots into algorithmically-designed beige mush, passive-listening Spotifycore and ghost artists. 100 gecs, in its maximalist re-purposing of sound, might just have captured some of the last vestiges of glee in listening to something that feels brand new in a musical age where pop is most successful when it isn’t. Perhaps the gecs are the way out of Spotifycore.