Darius Kazemi wants you to know how games are made. In Jagged Alliance 2, the fifth title from Boss Fight Books, he covers the history of the game’s developers and development, the fan and critical reception of the series, and the intricacies of its design. But Kazemi goes further, writing a book with concerns broader than this one game. While his love of Jagged Alliance 2 (the game) is clear, it’s his interest in the material history of game-making that shines through.

In Jagged Alliance 2’s intro, Kazemi positions his book as a sort of reply to Killing is Harmless, Brendan Keogh’s 2012 book which lovingly analyzed Spec Ops: The Line. Where Keogh focused on the game itself, offering analysis of its design and praise for its designers, Kazemi wanted to write a book that went beyond the game text, one which “took into consideration the economic realities that spawned its creation, spoke directly to its developers and publishers about the labor and money they put into it, and even looked under the hood at the code powering the player’s experience.” In pursuing this goal, Kazemi has written a book that extends beyond its subject matter, proving useful for anyone interested in this era of game development.

This is because, while Jagged Alliance 2 is a book ostensibly about the game whose title it shares, Kazemi treats the game not only as a subject in its own right but also as a case study. Over the course of Jagged Alliance 2 , Kazemi traces a line from the early 1990s to the early 2000s: from a time when hobbyist developers submitted completed games to hungry publishers, to the era of three person dev teams working from contract to contract; from the autonomy of the small, well-funded, in-house studio, to the publisher-dependent and market-driven dev houses of the 2000s. This is a book about the development of Jagged Alliance 2, but it’s also a transitional history of gaming. And while the author clearly misses an era of designer-driven development, he also avoids a rose-colored look at basement-era development. This isn’t nostalgia, it’s a practical accounting of what was lost.

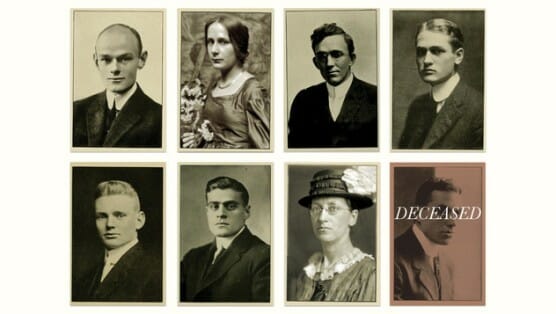

Like other books in the “game history” genre, Jagged Alliance 2 begins with an overview of the series’ major players. Kazemi gives the reader the story of Sir-tech (the game’s original publishers) and paints us an image of Ian Currie, the game’s designer, bored at his day job before recruiting a good friend and a rookie artist to design his dream game.

Kazemi often lets these people speak for themselves, in big block quotes, but he doesn’t let these statements hang unquestioned. Instead, he uses other developer quotes (or his own analysis) to provide a different perspective. He’s never confrontational or aggressive—Kazemi’s goal isn’t to contradict claims, but to complicate them, and to show how Jagged Alliance 2 owes its success to a web of causes.

While Kazemi clearly respects Currie’s design skill, he doesn’t make an auteur out of him. It’s not just that Currie had a great acumen for game design, it’s that the conditions of Jagged Alliance 2 ’s development allowed (and even encouraged) the use of that acumen. Kazemi considers dozens of factors that led to both Jagged Alliance 2’s development success and for the decline of the “mid-tier” developer and publisher. He notes that the spread of new CD-ROM to consumers allowed Jagged Alliance 2 to feature characters with character-building voice clips. The youth of the game industry meant that it hadn’t yet fully pivoted to market-first decisions, which let small studios like Sir-tech Canada maintain autonomy. New coding practices let developers build finely balanced, heavily iterated levels. Retailer practices allowed for new games to slowly gain an audience over a period of months, instead of being returned quickly if they languished on the shelves. When new, even higher fidelity visuals became the norm, asset cost went up, and it became hard to justify the “small touches” that made games like Jagged Alliance 2 what they were.

It’s this emphasis on non-human actors that shifts Jagged Alliance 2 away from Masters of Doom or Console Wars. There aren’t any backstabbing execs, broken friendships or dramatic monologues here. If Jagged Alliance 2 has a villain, it’s the series of systemic and technological changes that have cost us developers like Sir-tech Canada.

Throughout the book, Kazemi seeks to ground and demystify Jagged Alliance 2, so perhaps it should be unsurprising then that he struggles with selling it to us as a fun game to play. Kazemi explains how the Jagged Alliance series plays largely through comparison with other games in the genre. Where X-COM is a game about preparation and defense, Jagged Alliance is a series “about offensive strikes,” mobility and claiming new resources. Where real-time strategy games let players issue broad orders to a mass of faceless soldiers, Jagged Alliance gave players precise, turn based control over a handful of mercs with unique character.

His descriptions are accurate, and interesting, but they don’t make me want to rush out and replay the game. (In fact, the most alluring description of what Jagged Alliance 2 feels like to play comes not from Kazemi, but from Rob Zacny’s excellent foreword.) Perhaps in effort not to sound as joyous as Keogh in Killing is Harmless, Kazemi’s writing often feels sanitized. This is a shame, because Kazemi’s book is at its best in the moments where he combines his love for the game, his deep knowledge of its history, and his skill at critique.

While one can read the book as a pure history of Jagged Alliance or an analysis of the ‘90s game industry, Jagged Alliance 2 is also (subtly) about logistics: the flow of people and goods. He locates Sir-tech’s roots in freight shipping software, discusses Currie’s work on the Canadian rail system, explains the relationship between major retailers like Wal-Mart and game publishing, and spends time carefully giving us an overview of the logistical movements of a studio and its workers.

This focus on the logistical extends to Kazemi’s analysis of the game, and it’s in one of these moments that he pens one of the book’s most memorable passages. Among the many mercs you can hire are Vicki, a vintage car dealer from Jamaica, and Gasket, a good ol’ boy mechanic from Kentucky. Vicki knows that Gasket’s racist—so racist, in fact, that she refuses to join your squad if he’s been hired. If the player wants to recruit Vicki, they have to fire Gasket, and then wait the 24 in-game hours it takes for Vicki to arrive—going short-handed for a couple of fights. “In this way,” Kazemi writes, “a simple clash between characters can force the player to make a difficult strategic decision.”

This “simple clash” only exists because Sir-tech Canada was a studio working with the right technology, in a moment that offered them the financial flexibility to give designers time and autonomy, and staffed by people interested in simulating both logistical flows and multi-cultural contact. In effect, Kazemi’s whole project is to prove that Jagged Alliance 2 is itself a result of this sort of “clash” of causes.

In the final pages of the book, Kazemi writes that “Jagged Alliance 2 isn’t just impressive for the vast array of things it tries to simulate. It’s impressive because these aspects are interconnected, creating a game that is much more than the sum of its parts.” The same could be said for his book, which weaves together industrial history, design analysis and Robert Yang-style code diving. The result is not just a good read, but also a blueprint for holistic critique.

Jagged Alliance 2 was written by Darius Kazemi and published by Boss Fight Books.

Austin Walker is a PhD Candidate in Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario, writing about games, labor and culture. He writes about games at @austin_walker and at Clockwork Worlds.