Before I left for college, I asked my dad to give me a list of his favorite songs for me to listen to when I missed him. At the top was Jim Croce’s “New York’s Not My Home,” off his third LP You Don’t Mess Around With Jim. Like any self-respecting ‘70s kid, my dad spent much of my childhood handing down his favorite music, teaching me the words to “Thunder Road” before I could count, sitting ten-year-old me in front of a stereo blasting 4 Way Street. But Croce hadn’t come up until that moment. I think somewhere in his subconscious, he knew to save Croce for this exact time in my life.

One of John Sollazzo’s Top 10 Favorite Songs of All Time, “New York’s Not My Home” quickly became a fixture in my college listening rotation, soundtracking countless bittersweet flights back West, pensive walks home from class, late-night balcony sits. Faced with the concept of real change for the first time in my life, I developed a penchant for nostalgia-as-survival that I haven’t quite been able to shake since. I found myself reaching backward, replaying old memories, combing through texts and photos to ensure my life happened the way I remembered it. Croce fed that impulse while keeping sentimentality at an arm’s length; vague enough to paint my own picture, but specific enough to jerk some tears from time to time. I needed the reminder that New York wasn’t my home, at least at that moment in time.

Maybe it’s the mustache—huge, walrus-like, almost cartoonishly paternal—or that warm voice and easy smile, but I think people (maybe just me) forget that Croce wrote most of his music in his twenties. He died at 30. Due to his repertoire (acoustic dad-core, wisdom-laced lyrics), he often gets cast as a kind of folk sage. But really, he was just some guy from the outskirts of Philly trying to understand his life. He was at once a floundering mess and a source of guidance, reckoning with time’s infinite passage and untapped potential through character-driven narratives and vignettes created in the image of, and in direct response to, the American Dream, which he saw his own parents achieve after emigrating from Italy. There’s a comforting lack of certainty, with Croce spiraling through ruminations that sound similar to the past few years inside my own head: What if the best isn’t coming? What if I don’t make it? What’s the point of trying?

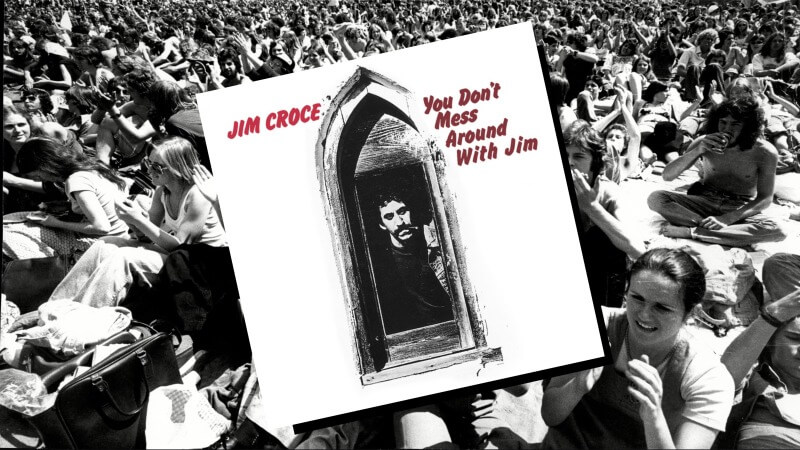

When you’re a teenager, Jim Croce sounds like a type of wayward spirit guide, his soft and steady voice and modest mantras like something an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex couldn’t fully comprehend without a little nudge. In the thick of your twenties, you realize he’s a peer, endlessly searching for meaning under the external pressures to make something of yourself. You Don’t Mess Around With Jim was Croce getting “serious” about music after years of false starts. His debut, Facets (1966), came out a year after he graduated from Villanova and was funded by a $500 wedding gift from his parents. He spent the next few years playing small gigs with his wife, Ingrid (they even released a duo album), enlisted in the National Guard to avoid the Vietnam draft, briefly moved to New York, and worked various jobs, including construction and truck driving, to make ends meet. In 1970, Croce began working with guitarist and songwriter Maury Muehleisen, whose riffs (some of the most lasting and resonant in all folk music) helped Croce’s songs feel whole. The pair would write and perform together until the September 1973 plane crash killed them both, an event that simultaneously ended and began Croce’s legacy.

I’ve always felt a link between my own fixation on the past and Croce’s. His writing simultaneously looks back and hopes forward, piecing together human relationships with his own experiences to make something that mirrors how memory tends to work: fragmented, teetering between reflection and projection. His use of characters as stand-ins for his own questions and the persistent reach for something just out of frame mimic the ways I still tend to replay memories: making sure no detail goes unanalyzed, conjuring up visions of alternate universes, wondering if everyone else remembers it the same way I do. Rather than try to figure it out, Croce sits in it.

The title track kicks the album off with a warning. Big Jim Walker runs the pool hall until another guy, Willie McCoy, murders him for owing him money. It’s told like an old saloon fable with its choral backing vocals, honky-tonk piano, and overall twang, but the message stands true: nobody’s untouchable. These character studies, based on those Croce encountered in his odd job years return on songs like “Hard Time Losin’ Man,” where a guy can’t stop getting scammed (cars fall apart, weed ends up being oregano), or “Rapid Roy (The Stock Car Boy),” a sketch of a “dirt-track demon” with cigarettes folded in his t-shirt and tattoos that say “baby” and “hey.”

You Don’t Mess Around With Jim holds its emotional depth at the center, with three songs that offer their own tales of the different ways we look back on love and relationships. “Photographs & Memories,” “Walkin’ Back to Georgia,” and “Operator (That’s Not the Way It Feels)” are stacked perfectly on top of one another. “Photographs” mixes Croce’s tender tone with sweeping strings, repeating a dissonant motif rather than a full chorus (“Morning walks and bedroom talks / Oh, how I loved you then”). The song ends with an unresolved chord, much like memories can suddenly flash through your mind without warning.

On “Operator,” Croce inserts himself into a scene rather than creating a character. The song unfolds as a phone call to an old love, with Croce unloading on the switchboard technician before he even gets patched through. At first, he wants to prove his indifference (“And give me the number if you can find it / So I can call just to tell ‘em I’m fine”). But by the end of the song, he’s gotten everything he needed off his chest (“Well let’s forget about this call”) and doesn’t even need the real thing. “Walkin’ Back to Georgia,” more wistful than wounded, leans melodic, with another one of those Muehleisen riffs that hasn’t left my head since I first heard it. (Those bends! They make me tingle!) Croce’s run-on phrasing adds to the conversational tone, switching between talking about and talking directly to Georgia.

As much as Croce focuses on the past, he doesn’t forget about the Tomorrow. On “Tomorrow’s Gonna Be A Brighter Day,” tomorrow is a declaration of loyalty in the face of hard times, and a promise to do everything and anything to make things easier for someone else. For closer “Hey Tomorrow,” it’s a resignation wrapped in hope: “You gotta believe that / I’m through wastin’ what’s left of me / ‘Cause the night is fallin’ and the dawn is callin’ / I’ll have a new day if she’ll have me.” “Time In A Bottle” is a haunting acoustic track carried by its repetitive Spanish guitar riffs and Croce’s aching head voice. It gained wider attention following his death. The desire to stop time to spend as much of it with someone else suddenly became how everyone else was feeling about him. Croce, ultimately and heartbreakingly, succumbed to his fear of things slipping away too fast. In the years that followed, You Don’t Mess Around With Jim took on a second life. What began as a modest, rough-edged portrait of a young songwriter navigating failure, love, and inertia was suddenly viewed through absence rather than momentum.

The record spent five weeks at #1 on the Billboard 200 in early 1974 and was the fifth-best-selling album that year. Everyone can still hum along to at least one Croce song by the time they’re ten (whether or not they know the man behind the tune), but the harder truth is he might not have gotten that far if he hadn’t died. The real loss is how little we got, and how much of it only mattered afterward. I think that’s why “New York’s Not My Home” landed so hard when my dad first put it on that list. It was a song about dislocation and uncertainty, something I didn’t fully understand until I was alone for the first time. Now, when I go back to You Don’t Mess Around With Jim, it feels like my own little bottle of time, a way to collect feelings, people, and versions of myself before they get too far away.