Color Theory: Palettes of Pain and Peace in Midsommar

Color Theory is a Paste column that examines and critiques the literal and symbolic use of every hue under the sun, within the works of some of cinema’s greatest auteur filmmakers. You can see every entry in the series here.

Ari Aster’s Midsommar caught cultural fire in the summer of 2019 as quickly and consumingly as its victims, and for good reason. The writer-director’s second film after Hereditary flows seamlessly from shadowy misery to sunny retributive horror without ever losing its firm tonal, thematic, and technical grasp, exercised with the command of a filmmaker with decades under their belt. It’s no surprise that it hangs perpetually in the top 20 most popular movies on Letterboxd or that successive rewatches might fire cinephiles up about Aster all over again.

With the wide release this week of his fourth feature, Eddington, we look back at the variegated color extremes of Midsommar in 13 shots that exhibit Aster and company’s acute attention to detail within the frame–the kind that elevates every aspect of a film.

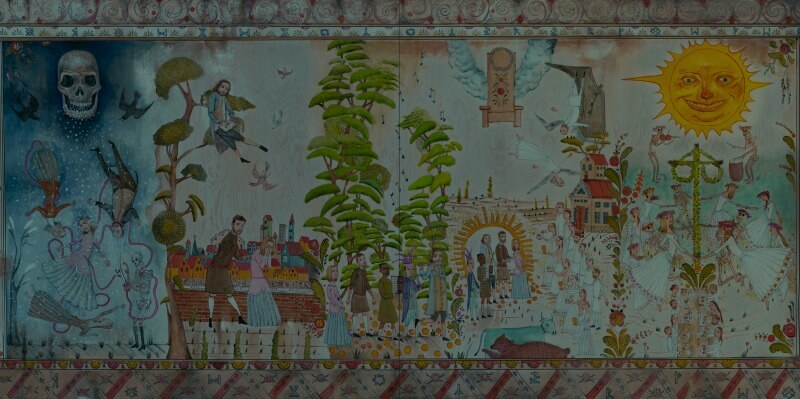

The pictorial, polychromatic prologue-mural to Midsommar–like the sprawling illustration on the interior walls of the Hårga dormitories–stretches across a canvas of pale Scandinavian wood with a swirling grain and a cool, mournful hue. From left to right, it depicts much of what’s to come in chronological order, giving characters up as directly as dressing Mark in a periwinkle jester hat (similar to the one he’s burned in) while completely askewing developments as critical as Christian’s comeuppance. The multi-paletted color of the plot panorama points to the wild world of Midsommar that awaits us.

A cherry-nosed, dandelion sun–that mimics Dani in the final shot–grins down the lens in beaming conquest while the sightless skull sitting on the opposite side hangs in a shadowy, Prussian blue doom over the whole diptych, the rest of which is depicted in daylight. Below the skull spills a gradient of icy midnight tones that foretell the introduction’s mood, a vascular-purple carbon monoxide hose running through Dani and her family like the grim reaper’s scythe in fresh form. After a long look, the image will part down the middle to reveal the first (non-painted) shot, hurling us into the emotional trenches of those grieving blues.

Midsommar opens as if it always meant to upend its future pop culture expectation for bright, grisly, kaleidoscopic violence. The Swedish acts of Aster’s sophomore triumph catch fire in such luminous spectacle that it can be easy to forget just how sunk in the suffocating dark the opening American act is. Instead of a bleary-bright, Swedish flower-power aesthetic, we begin in the muted, monotone haze of a dull powder blue blizzard. A flurry of confusion and depression in meteorological form, the shot situates us Dani’s mental state immediately.

To get from confusion to depression, the deadening color darkens over a series of nine shots of snowy nature that range from silver- to stone-blue, the last shot in the series settling on a swarming darkness of pine trees that makes the shot above look shiny. Then, abruptly, Aster rips us back into Hereditary, to the darkest place of all: the suburbs, as stripped of color in the night as it is of its willingness to nurture critical thought.

There’s a foreboding depravity in the pitch dark of Dani’s hometown suburbia, which swallows the embers of street lamps and garage lights spattered across it like already-dead stars in the night’s sky whose lights have yet to fade, or deceased family members yet to be discovered–a depravity described in color in Terri’s farewell message to Dani: “everything’s black…” So it is, Terri. The phthalo blue-roofed blackness invades the suburbs like a disease, pitting a smothering, cultureless darkness against the purifying, ritualistic brightness of Hårga. Both settings harbor horrific death, but they’re designed, lit, and colored to Dani’s perspective: the fear in a place that refuses to acknowledge death versus the cathartic comfort of a place that embraces it.

Between the bipolar palettes of the beginning and end, the tenebrous former will temporarily cage her, while the summer solstice light of the latter will set her free. Outside of the first act, the movie will only get this black again in nightmares and temples. Take, for instance, the stark-dark religiosity of the Rubi Radr temple where Ruben’s drawings are interpreted, outsiders are drugged and communally raped, and some form of holy incest takes place to inbreed the next oracle. Or the phantasm of Dani breathing smoke surrounded by vacuous night. But, stateside, the frames are almost always benighted, the blanket of blacks and deep blues playing like an emotional anvil crushing Dani.

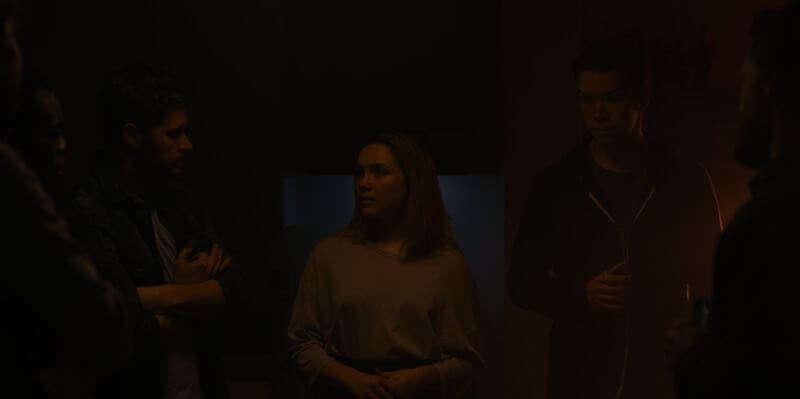

The surreal amber light of the pre-Sweden house party is atmospherically gorgeous, like the pervasive glow of a fire that’s not there. In other angles on the scene, it dominates as the only color cutting through the shadows of pot haze in an otherwise unlit student apartment. From this angle, however, it’s largely cut off, barely shading them in burnt orange light. Dani stands square in the steel blue frame of the doorway behind her, which gives color to her anguish, along with the painful reality of the moment unfolding, in which she unfortunately (per Pugh’s perfect expression) learns that her boyfriend planned a two-week, cross-ocean trip without her in the aftermath of her entire nuclear family’s suicide-murder. In this palette, the orange luminescence of the non-existent fire foretells the warm welcome that awaits her–in color, yes, but also in placement on the right side and placement opposite of Christian.

Aster establishes this geographical color code in the initial shot of Dani, and employs the blue-orange dichotomy often. Planted in the cold, lifeless, fluorescent light of her computer screen, faced with the ambiguous dread of her sister’s ominous message, warm lamplight flanks her from the right, an emblem of where she’ll end up: in the light of a round-the-clock sun, at home in the nurture of a new family, past her trauma at cult costs. In the first act, fiery light almost always flanks Dani from the right, just like blue light usually floods the frame with melancholy or at least tinges the left side with it amidst the darkness.

On the flip side of that color code coin, Christian is almost always depicted in darkness or emptiness in the opening act – slumping in shadowed bars, avoiding conflict in low-light rooms, disembodied in mirrors out of frame, represented through empty chairs–and with the warm light typically on his left, signaling his future regression into the fire. In a few of his opening frames, he’s so buried in shadow he’s nearly cut out of the image in a Christian-shaped stencil.

Here, the identity-erasing darkness is a manifestation of the ash he will become, the snow floating between him and the warm light like particles of said ash drifting from the fire. The Christmas lights of the climbing, violet blue tree looming over him and the crimson-lined house to his right are clear color depictions of the sheer grief and carnal brutality that await him in his relationship with Dani. The couple get their first real taste of the latter at the Ättestupa.

Move over, Lion King. There’s a new Circle of Life tradition atop a pointy rock overlooking a breathtaking landscape. But, instead of the Pride Lands, we’re in Hälsingland; instead of Simba, we have the boy from Death in Venice grown up; instead of speaking Zulu, we’re reading Elder Futhark; instead of birth, death–an equally important part of the cycle. Surely, Rafiki would approve of the Hårga’s circle-of-life-affirming traditions. Surely.

The marbled, earthy neutrals of the gorge rock range from paperback vanilla to fossil shale to desert sand cream, the ivory-linen hues camouflaging the Hårga in their cultish off-white attire on the ground. Similarly, at a distance, the sacrifice standing eerily at the edge of the cliffside matches the slate shade of the rock perfectly. Say what you will about the Hårga people, but there’s no denying their alignment with nature, as the costume and location harmony make abundantly clear. The guests, on the other hand, are like sore thumbs in their dark outfits.

The inanimate color aptly strips the scene of life (notice how few trees are growing within the gorge) while painting it in a harsh but beautiful light. If the sky blue between the off-white clouds was any fainter, it would be gray. Even the rich forest greens beyond the sacrificial site fade into near-colorless neutrals. The color of the bleary-bright frame–like an existential blank canvas ready for two pulsating red accent marks–gives off an ethereal, peaceful afterlife aesthetic that flies in the face of the visceral, primal event about to take place.

After the burning of the elders–watermarked in the firepit of mangled bodies in the middle of the frame–we find Dani mid-meditation. The fading specter of village people surrounding her, palms open and outstretched, comes at the back end of a wonderful cross dissolve transition that centers and cements Dani’s significance to the villagers as their forthcoming queen.

The lush, sea green grass swallows her feet in height as the trips swallow them in literal, Annihilation-esque symbiotic nature sequences, signaling Dani’s belonging among the Hårga people. With Dani surrounded by mounds of golden-brown straw that will burn Christian in the end and happen to match the color of her hair, which she’s let down for the first time, we begin to see signs of her acceptance in the frame’s color: The neutral tee she switched out in place of the dark one, the dim light of nature in contrast to the deliriously bright light that has dominated since she arrived and pretended like everything was fine, and the deep, somber shades of the grass. On the far left, Christian, enters the frame in all dark clothes, an omen and direct contrast to the color of the Hårga he’s walking through.

The tranquility of the village and serenity of the people have a devious effect similar to the colorful brightness of the cinematography. Soft, chalky Scandinavian browns of varying natural wood tones make up the handmade structures of the village. Ribbons of light and dark pine color the barn-like architecture, the characteristically straight grain of the stained Swedish wood rushing like a river when the psychedelia begins. Yet, inside the hypnotic, warehouse-sized structures sit singularly disturbing scenes, like a man flayed open from the back, somehow kept alive in the process, his body now a feeding trough for chickens, or an inbred child left to their own devices in the dark under the guise of divine prophecy, or the face of a fool skinned and worn like a Leatherface mask.

Rolling hills of seaweed-shaded trees bleed into the fresh, verdant greens of the countryside, interrupted occasionally by dirty splotches of well-worn ground. Gentle flamingo pinks and cerulean blues bespeckle the open pasture with false hope and dignity. The glowing garb of the village inhabitants radiates a celestial pagan purity that matches the clouds in the gauzy, beau blue heavens above them. One can’t help but remember another famous cult that dressed in all white (and I’m not talking Leftovers).

Their whiteness, in skin and costume, is intentional. Like Nazis before them (or, would it be after?), and countless iterations of similar groups across continents and time periods, there is a strongly felt supremacy among Midsommar‘s Hårga found in their dress, something innate (dominion over others) represented proudly in something elected (a uniform). Unlike Nazis, however, the Hårga bear all the signs of a supremacist group unspokenly, in behavioral disguise. It doesn’t take long for us to see through their eerie charm and into their iniquity, but before we do, the accent marks on their clothes give us little clues in color.

Seen here just before the Ättestupa, in stern, solemn meditation on the reality that two elders in their community are about to commit suicide, albeit honorably, a stretch of Hårga folk don the traditional, individualized attire. A garden of perfectly plated food and drink, too pretty to consume, is set before them. The pearly and creamy whites of their cultural vestments, backgrounded by an orange- and yellow-tinted hunter green tree line, are accented almost exclusively with the same shades of royal blue and blood red. The former points to their self-instituted cultural supremacy, how they see themselves above others, while the latter winks about the putrid violence to come, giving a sinister undertone to the otherwise quaint stitching. Yellow is common in the outfits, too, but it’s almost invisible to the naked eye in the sun (see: elderly woman’s apron).

As the story goes on, the pleasant, underlying evil of Pelle and the Swedes–obscured by smiles and linens fit for a luxury beachside villa–melts frighteningly into hot-colored Klan imagery grounded in ritualistic bonfires, unwilling human sacrifices, giant runes, and blazes of human flesh. Before the May Queen competition, a deacon of the village announces that they dance in “life-holding defiance of the Black One.” The competition itself is centered around a large, wooden, cross-like structure that instead of being burnt to the ground is decorated with rainbow flowers, floating buttresses, and hoop earrings. They save the burning for the pyramid temple.

The menacing stance of the figures combined with the all-consuming sheen of the fire around them–adopted in different ways by the wood, the chameleonic white robes, and the silvery tribute onesies–gives the Hårga a dark, villainous demeanor. And the piercing saffron yellow of the insignia circles above them, which match the pyramid’s exterior, are like sentries’ eyes with navy, diamond-crossed pupils. As if the symbols aren’t enough, the soft, hallowed glow flooding in from the outdoors accents the top of the frame with the blinding color of sanctification felt by the Hårga.

The ancient rituals the Hårga follow to feel that way are depicted in the zealotry of their barn-dorm walls. Sweeping interior murals play like infinitely designed accent marks on an otherwise empty canvas of baby blue and gray-white wood. The baby blue beds and their blankets, like the walls, are strewn with markings and patterns that give the whole place a fairy tale aesthetic that harkens back to Goldilocks and the Three Bears (two of those four characters are accounted for in Midsommar).

From certain angles, the beams intersect to mirror the brighter side of the icy images the film opens on, the sleeping quarters a bastion of cold and sparse light that isn’t pleasing, per se, but whose light blue gleam has a cleansing quality much more friendly than that of the fire. It’s in this room, after all, that Dani will finally howl through her pain in guttural, communally echoed screams. But, for now, the decisively dark colors of Dani’s outfit show that she’s ready to leave, that she wants no part of the Hårga lifestyle.

After Pelle convinces her to stay by diving headfirst into her trauma (the room has a magic touch), she changes back into the neutral nude tee she was wearing when she arrived, re-opened to what the community has to offer. The color of her clothes often reflects her inner posture. Her embrace of the culture and traditions soar to new heights when she puts on the Hårgacore linen competition dress and again when she dons the May Queen flower dress.

The color of Midsommar takes on a new varicolored vibrance and textural menagerie once the May Queen competition begins: prismatic rainbow flares of self-prophesying vision, mirrored tables as far as the eye can see, floral bouquets as sex beds, dizzying dissolves of sunbathed dancing layered over each other to create a translucent lasagna of flower-crowned Danis, technicolor blossom slug suits (i.e. May Queen dress), newly warped vision, you name it. As Dani’s world turns upside down for the better, the color key is largely left behind in the name of the kaleidoscopic chaos that Aster renders in the sublime.

Among the elaborate garland, bucolic, unfamiliar tinctures of lavender, indigo, and orchid creep out from behind the dominant shades of cobalt blue and canary yellow. Radiant rosey reds, cadmium oranges, champagne whites, taffy pinks, and more adorn the greenery so thoroughly you can hardly see it. Half-shadowed, half-lit, the mane of vibrant flora can be seen breathing and radiating some kind of energy. Still confused (and tripping pretty hard), Dani does not like what’s going on. And she’s going to like what she finds even less. But the shadow is behind her, and the light, situated on her right once again, precipitates how she’ll feel once it’s all said and done (see: final frame).

Speaking of the end of Midsommar, let’s talk about yellow. From Dani’s arrival to her ascendency, yellow leads the way like an oracle of color. Behind the camera, buttercups, goldenrods, and rapeseed emblazon the forested path into Hårga that leads our unknowing protagonist through the looking glass of the dusty dandelion shards forming the sharp, grandiose entryway. Mustard flowers dot the village pasture and acidic tints of yellow are nestled in among the trees. The color can stand for optimism, inspiration, and joy as strongly as it can stand for caution and deception, all of which it fully represents here, depending on if you’re looking from Christian or Dani’s perspective.

The hard, fresh, unreflective marigold of the sacrificial temple is so stunning, so regal, it’s as if gold was simply stripped of its sparkle. It’s like a brand spanking new version of the yellow shade of the shard-ed entryway, but where the temple was built within the year (as it will be again), the archway’s color has faded over decades in the sweet sun and unforgiving winters. Around the temple, a subtly transcendental evolution of color bridges the two sides of the frame – or the tonally disparate ends of the story – together, led by the heavy basil tones on the right that morph into a natural chartreuse on the left. The dew-catching sea of electric blue tarp runs like a moat of animated color around the sacred temple and lends it an even holier shrine-like characteristic.

As Dani would have it, the temple is only more beautiful when it’s burning.

Luke Hicks is a New York City filmmaker, film journalist, and musician by way of Austin, TX. He earned his Master’s studying film philosophy, theology, and ethics at Duke University and is the founder of the Brooklyn-based Art Mob Productions.