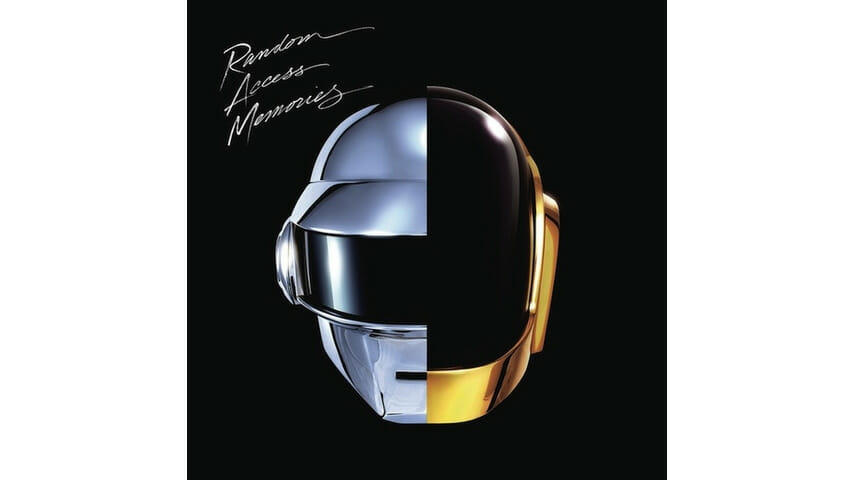

Daft Punk: Random Access Memories

Sasha Frere-Jones’ review of Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories baffled many in the critic’s corner this week as he insisted that this album asks, “Does good music have to be good?” This is actually a very fitting koan for a duo whose consensus classic Discovery received low-to-middling marks from Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, AV Club and Village Voice in 2001, narrowly beating out Macy Gray in that year’s Pazz & Jop poll in points even though Gray’s album had four more supporters.

Since then, Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo have released two other studio albums, Human After All which is savaged to this day, and Random Access Memories, which is released this day. It’s getting a mixed array of responses, which is odd. It’s a disco album, they agree on that, with a few theater pieces and suite-like formations boringly slotted as prog. Prog has surprise to it, whether it’s a screwy time signature or a monkey-wrench key change or some other unconventional defiance of pop formula. But none of the admittedly eclectic pilferings of Random Access Memories challenge or defy anything. They all evoke specific eras of film soundtrack or disco trend. The beats have grown less, not more, complex over time. They like it this way. A song like “Get Lucky” is no miracle; it’s not brought off by Pharrell’s uncomplicated voice or Nile Rodgers’ studied grooves. Giorgio Moroder’s not-disturbing voice is interviewed on the loving tribute “Giorgio by Moroder,” and the acted piece “Touch” gives away their real passion: being a soundtrack. It’s brought off because its stakes are incredibly low—wherein lies the rub.

Daft Punk fans are famously quick to get mad at Justice or Skrillex for burdening their fans with rock dreams, positioned as a direct affront to dance culture’s anonymity. From one old review: “Norman Cook’s Hawaiian shirts, Tom Rowlands’ yellow specs, Keith Flint’s bald-hawk and jackboots—all aspirational rockstar images that run counter to dance music’s needs by drowning it in nostalgia and making it difficult to locate in the here and now.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-