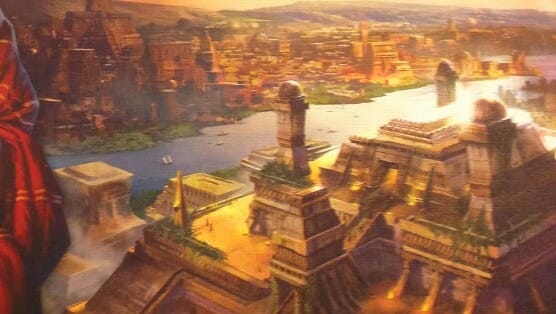

Tigris and Euphrates Boardgame

The 1997 game Tigris and Euphrates, by prolific designer Reiner Knizia, is an all-time classic in the genre, an abstract strategy game that’s easy to learn but that involves plenty of strategy and differs every time you play. It’s the second-highest rated game on BoardGameGeek among titles published before 2000—only El Grande, which is long out of print, rates higher—and is one of my top 12 games published in any year. Fantasy Flight Games has reissued Tigris with new graphics and a double-sided board (introduced in the mid-2000s) to allow for advanced play, and it’s an essential purchase for any boardgame collection.

Tigris and Euphrates is a tile-laying game with a clever scoring mechanic that rewards balanced play. Players draw tiles at random from a bag, with hands of six tiles hidden from other players, and lay tiles to create chains of tiles called Kingdoms, gaining points by placing their own Leader tokens in those Kingdoms and adding tiles of specific colors to the chains. There are four colors in the game: red Temples, green Markets, Black somethings, and Blue Farms, each of which has one special characteristic. Each player has four leaders, one per color, and may place any leader next to a red Temple to start earning points for every tile in that leader’s color added to the chain. If any player completes a 2×2 square of tiles in one color, the player may then convert those tiles into a Monument, flipping over the tiles and placing one of the six two-colored plastic monuments on top; at the end of a player’s turn, s/he receives one point for any of his/her leaders connected to a monument of the same color.

The heart of the game is the conflicts that arise between Kingdoms when the chains are connected—if you’ve played Acquire, there’s a little hint of that game’s mergers between hotel tile chains—or when one player places his leader of a specific color into a chain that already has another leader in the same color. Connecting two chains with at least one leader color in common is called a War, and the two affected players must compare their strengths in that specific color, adding up the tiles in that color in their respective chains, then adding tiles from their hands, with the attacker stating how many tiles s/he is adding first. The player whose leader wins the war gets one point for the victory and another point for every tile in that color in the vanquished kingdom, after which those tiles and the opposing leader are removed from the board. If the War connects chains with multiple leaders in common, the attacking player chooses which color to resolve first.