Coleman Francis: The Real Worst Director in Film History

It’s a safe wager that if you gathered up, say, 100 film fans and surveyed them on the identity of “the worst director of all time,” the answer would probably come back as Edward D. Wood Jr. And they would be wrong.

Ed Wood, for all his ineptitude and naivete, is simply the most infamous bad director of all time. That’s what happens when you have a film like Plan 9 From Outer Space on your resume, which was first enshrined with the “worst movie ever” title in semi-official fashion when it appeared prominently in Michael and Harry Medved’s Golden Turkey Awards in 1980. It actually helps that despite all their flaws, Wood’s movies are, by and large, amusing viewing experiences that lend themselves to cult screenings because watching them really doesn’t hurt that much. They’re the sort of classic, z-grade, no-budget shlock that is saved by their harmlessly earnest and generally sincere attitudes—just try listening to the alien dialog of Plan 9 without cracking a smile.

The films of Coleman Francis, on the other hand, do not provoke smiles. They don’t provoke laughs, either. Coleman Francis is the real owner of the “worst director of all time” distinction, but it’s not surprising that his work isn’t as well known, because once you’ve seen a Coleman Francis movie, the last thing you’ll want to do is see the others. What you’ll want is a time machine, so you can step inside and warn your past self not to engage in a terrible mistake.

With that said, the career of Francis is a fascinating one, with a surprising number of parallels to that of Ed Wood. I’m not sure if the two icons of bad cinema ever managed to meet each other in ‘50s/’60s L.A., but if they had, the resulting collaboration and combination of their acting stables would have been a momentous event in bad movie history, akin to the Yalta Conference between Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin. Likewise, I feel we should note that to really be “worst director” material, you need to have a multi-film career that received some kind of professional distribution. Thousands of would-be auteurs have shot handicam “features” from the comfort of their garages before disappearing off the face of the earth. “Worst” implies a greater determination—the ability to fail miserably, learn nothing from the experience, and then promptly fail again.

Ultimately, though, the reason that any of us still remember the works of Francis today is thanks to Mystery Science Theater 3000. As it did for Manos: The Hands of Fate, MST3k also injected fresh perspective into the filmography of Francis. The classic movie-riffing show featured all three of Francis’ feature films: The Beast of Yucca Flats, The Skydivers and Red Zone Cuba. It’s telling that they chose Francis—rather than the better-known Wood, MST3k tormented its captive satellite crew with films that were much, much worse.

Coleman Francis: The Beginning

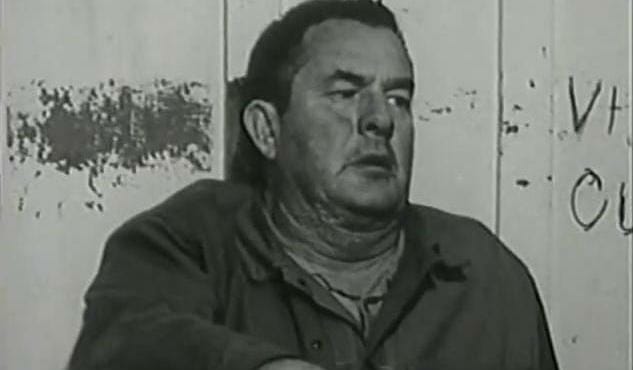

Coleman C. Francis was born in 1919, lived through the Depression, and was apparently bitten by the acting bug in the ‘40s when he moved to Hollywood. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a pudgy, not particularly attractive everyman, he didn’t exactly find juicy parts forthcoming, but he did play bit parts in many films, including, oddly enough, the sci-fi flick This Island Earth, which went on to be featured in MST3k: The Movie. Already, though, you can feel a certain desperation to his career—the guy showed up wanting to be an actor, but didn’t even get a CREDITED role for more than a decade, playing a detective in the amusingly titled and Roger Corman-produced Stakeout on Dope Street.

Soon enough, though, Francis’ attention turned toward potentially producing and directing his own films. Perhaps he was frustrated with his inability to break through as an actor in Hollywood, but for whatever reason, Coleman Francis had a fire lit under him; a desire to prove himself as an artist. What he didn’t have was funding to get a film project off the ground.

In 1960, though, Francis had a streak of luck: He met the creative partner who would end up financing (and starring) in all three of his films, one Anthony “Tony” Cardoza.

Cardoza was a highly decorated artillery gunner in the Korean War who returned to civilian life and became a welder on jet engines, apparently socking away a fairly sizable nest egg. He displayed an interest in acting, although he was completely untrained—perhaps this is what supernaturally lead him to the office of Ed Wood, where he was cast in the director’s last “major” film, 1958’s Night of the Ghouls, which was not released in any real capacity until 1984 because Wood failed to pay the film processing lab and it was literally held hostage. After that experience, one can imagine Cardoza believing that working with Coleman Francis would be a step up, but this was not to be. Together, the two would begin collaboration on their first movie, The Beast of Yucca Flats, with Cardoza paying and Francis writing and directing. Cardoza reminisces about the entire experience, and about Francis, who he affectionately remembers as “Coley,” in this interview, which I’ve quoted throughout.

The Beast of Yucca Flats, 1961

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

What a likable bunch of viewpoint characters.

What a likable bunch of viewpoint characters.