How Twin Peaks Tells the Story of TV’s Last 30 Years

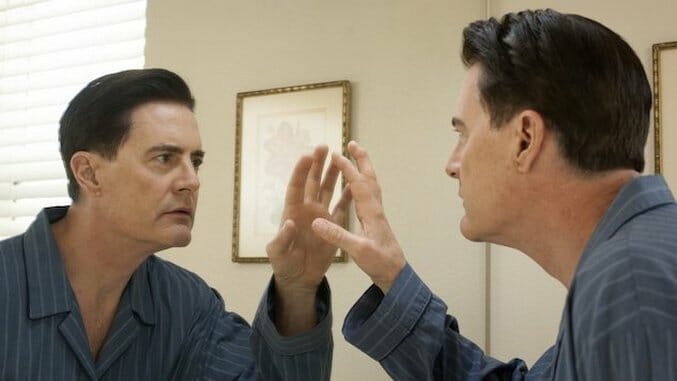

Suzanne Tenner/SHOWTIME

When Murder, She Wrote came to Netflix last year, my friends and I watched it unironically, entertained by its relentless sincerity and by Angela Lansbury’s charm.

As a teenager, I thought Murder, She Wrote was stodgy, wholly different from Twin Peaks, which premiered on ABC in 1990, airing opposite Murder, She Wrote and CBS’ Sunday night block. Twin Peaks came at the end of a decade saturated with crime drama: 1985 saw seventeen airing on the three broadcast networks. Styles ranged from the award-winning Hill Street Blues and the beautifully shot Miami Vice to the pretentious glamour of Hart to Hart and Remington Steele. These shows approached murder as something solvable in one hour, once a week, usually in a cloud of hairspray, shoulder pads and teal. It would take Twin Peaks and a shift in technology to radically change TV, from episodic and moralistic to immersive and authentic.

Prior to Twin Peaks, bodies were bloodless and murders were often committed off-screen. Except for Miami Vice and Magnum PI, writers and producers still reflected the standards of the broadcasting code of the 1950s, when networks were asked to remember that “television’s relationship to the viewers is that between guest and host.” Besides the implication TV is sentient, this reflects a polite paternalism, an admonishment against offending people with such graphic detail. Twin Peaks seems to satirize this idea by having each living room contain a TV playing Invitation to Love, a ubiquitous soap opera echoing plot lines of the actual show. But it seemed to take a decade for shows to stop sanitizing a genre about criminal behavior and its aftermath.

It’s not surprising that an industry measurement dating from the ‘50s cautioned politeness. Other broadcast guidelines are now worthy of a spit-take. Shows were entrusted to “respect the sanctity of marriage” and reflect reverence toward God and His powers. Networks were prohibited from presenting the “techniques of crime” or “shocking and alarming a viewer” with horror. “Criminals shall be presented as undesirable and unsympathetic” and law enforcement portrayed with respect. Murders weren’t just solved, the world was returned to a homogenous midcentury state, where families were usually put back together, heteronormative relationships preserved, criminals separated from the blameless. These boundaries were often pushed and notoriously difficult to enforce, but Twin Peaks took them as targets to raze, awe-inspiring from both a creative and cultural standpoint. Perhaps this is why Peaks devotees felt so responsible for spreading its gospel, eagerly perpetuating the momentum of revolt.

Ultimately, the charmingly innocuous, Murder, She Wrote would outlive Twin Peaks. Other than Columbo, it was the longest running series of its 1985 class (twelve seasons) and, along with Hill Street Blues, one of the most influential. MSW averaged 25 million viewers per episode in 1994-95, its eleventh season. That’s more than two and a half times the viewers of the season finale of Breaking Bad, a far more nuanced show. MSW featured a parade of guest stars, jump-starting the careers of Courteney Cox, George Clooney, Linda Hamilton and Bryan Cranston. Its popularity was not simply a lack of choice, but an embrace of the familiar.

We all tuned into the ‘80s crime drama for eye-candy, not the brutality of human transgression. Actors remained camera ready, even when standing over a corpse. In the Magnum PI episode “Echos of the Mind,” Tom Selleck, defending Sharon Stone from her evil twin Sharon Stone, is attacked by Rottweilers. After one-liners in a palm-filled triage room, Selleck is his same cool-headed, attractive self. In “Wave Goodbye,” his close friend is found murdered on the beach, and Magnum tolerates wisecracking Honolulu PD before speeding away in his Ferrari to solve the crime. For all the murder in a decade of TV, almost none produces recognizable trauma like Twin Peaks. Compare this to Sarah Palmer’s raw scream following the death of her daughter, and the image of Ronette Pulaski dissociatively flexing her ligatured wrist as she crosses a train trestle in a slip.

When trauma unfolds on camera in clear detail, we share in both the brutality (Laura wrapped in plastic) and the aftermath (Sarah’s surreal scream) in a way that’s frighteningly intimate. Part of the reason American Horror Story is so upsetting is because we watch characters’ lives unravel with each appearance of the supernatural, even when it’s metaphorical. We’re given the opportunity to see the threat of violence before it occurs, in true Hitchcockian style.

This unflinching gaze has been a gift to contemporary writers, whose characterization has become much more dimensional in cable network shows like Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, True Detective (Season One), and streaming service originals like House of Cards. Coupled with less murder-of-the-week plotting and unconstrained by mass-broadcast standards, writers have unleashed characters who demand our attention and empathy—whether they’re criminals, dirty cops or characters struggling to live in the aftermath of violence.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-