Lashonda Katrice Barnett

Redemption Songs

Gifted artists sound off on both muse and music

In a country where celebrity obsession seems incapable of bottoming out, it’s easy to forget that at least some of the stars we love (and hate on) are actually gifted artists. And in the music industry, where racism and sexism still have their say, even the most talented black female artists are often typecast—and dismissed—as “girl singers” or “divas.”

Take, for example, Beyonce?: When was the last time you read a story about her that didn’t use the term “bootylicious,” or that took her seriously as a songwriter? Interviewers rarely question the R&B idol on her writing process, despite her 2007 Golden Globe nomination for best original song (for “Listen,” from the Dreamgirls soundtrack). Yet the press informs us relentlessly of her dance pratfalls and of Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunctions.” Even a serious young musician like Alicia Keys has to push her public to look beyond her dolled-up music video image and remember that she’s a composer.

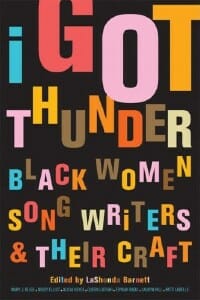

Beyonce? and Keys are not among the songwriters interviewed in I Got Thunder, an admirable collection of conversations edited by LaShonda Katrice Barnett, a young professor at Sarah Lawrence College. But the book resounds with the voices of women who have influenced them both—and whose music has influenced us all.

Most of the 20 women chronicled in I Got Thunder—which takes its name from an Abbey Lincoln tune— are famous, if not household names, including Lincoln, Dionne Warwick, Chaka Khan, Nina Simone, Miriam Makeba, Odetta, Shirley Caesar, Joan Armatrading and Nona Hendryx. Barnett approaches them as serious artists, not as celebrities. “None of the singers I spoke with set out to become famous,” she reports in her introduction, “nor does fame creep into these conversations even as a subtopic.”

The author’s goal for these oral histories, she adds, “…was to illuminate for music lovers and wouldbe students of this art form a crucial but understudied and underappreciated component of black women’s music-making: the role of the creative process.”

Barnett achieves this goal, and then some. But her passion for the music prevents her from assuming an overly academic tone. Instead, she invites readers to eavesdrop on her deeply intelligent, intimate and occasionally rollicking conversations with some of the women who have voiced the collective American (and global) soundtrack for the past 50 years. She also shows us that these women have played a large role in writing that soundtrack as well. Just think how impoverished it would be without Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam,” Chaka Khan’s “Sweet Thing,” Joan Armatrading’s “Willow” or Brenda Russell’s “If Only For One Night.”