Moshe Kasher on Crowd Work: “Everybody’s a Monster”

Photo by Art Streiber, courtesy of Pitch Perfect PR

On the surface a crowd work album sounds like a terrible idea. Crowd work is inherently built around the direct connection between a comedian and an audience, and it’s already hard to replicate that in a filmed special. How could it possibly work in an album, where you can’t even see the people the comic is talking to?

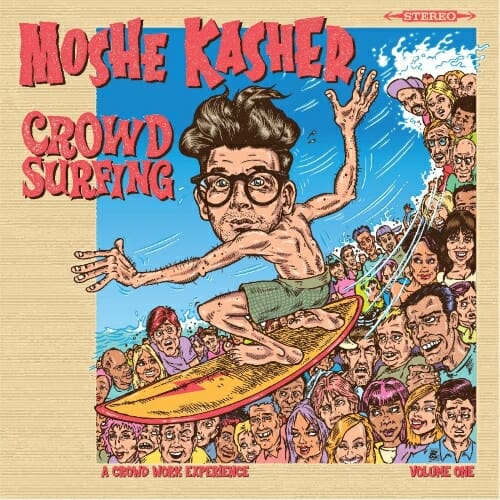

Moshe Kasher, one of the modern masters of crowd work, has thought long and hard about that conundrum. You can hear his findings on Crowd Surfing, a new album of nothing but crowd work that was released today by Comedy Dynamics. Instead of singling out audience members, he lets them come to him, passing a microphone around the room and asking if anybody has any interesting stories to tell. Those stories, and Kasher’s reactions to them, are more hilarious than any jokes about somebody’s appearance could ever be. The result is the first great comedy album of the year, and a deep dive into a crucial part of Kasher’s live act that has never been captured for posterity this thoroughly before.

Paste recently talked to Kasher about Crowd Surfing and the nature of crowd work. He was incredibly thoughtful and detailed when talking about what he looks for in an audience, what kinds of problems a comedian can face when doing crowd work, and why it’s worse to go easy on a differently-abled audience member than it is to fully engage with them as he would anybody else in the crowd. If you’re a young comic still coming into your own, or just a comedy fan who’s interested in the process behind the act, you’ll probably learn something useful from Kasher’s insights.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Paste: When you’re doing crowd work, do you look for distinctive looking people?

Moshe Kasher: 100%. I’ve come to realize about myself that the Moshe Kasher show, if there is such a thing, is always a show—it’s never just my material, it’s always one part material, two parts me going off the cuff, me riffing with the audience or just riffing on the situation, and if you’re a person who performs like that, where the real quintessential experience of seeing you is that you want to be dynamic and in the moment and of the evening, then you will start to become a hungry predator. Not in a cruel way, but I straight up will, if there’s access to the audience [before hand], I’ll just kind of scan the room a little bit and be like “oh thank God, there are some weirdos in the front.” You want that. You pray for that. The worst thing ever is when you walk out on the stage and you’re a crowd work person and it’s just like six of the same golf gear, golf clothing catalogue couples and you’re just like “what am I going to do with this.”

Paste: Do you find yourself falling back on your regular set when you have that kind of audience?

Kasher:: I hate how sincere what I’m about to say sounds, and if it sounds canned, that’s because it is, because I’ve thought about this, and it’s as close to an actual philosophy as I come to, in regards to stand-up comedy, specifically in regard to crowd work, which is that every crowd has a story in them, and if I didn’t find it, it’s not because it wasn’t there, it’s because I didn’t find it. I somehow didn’t do my due diligence as a performer. Even quote-unquote “boring” looking people, nobody’s really boring—everybody’s a monster.

Paste: On the album, you sort of let the crowd come to you, instead of picking people out, you have a microphone going around, and you ask if anybody has a story to tell. Why do you take that tack?

Kasher:: I was specifically dealing with the limitations of the audio format as it pertains to crowd work. Crowd work has this feeling of being very temporary and of the moment, and I think that’s why it sometimes gets a bad rap or a stigma. If you see it or hear it sometimes it feels like “well, if I was there that could be funny but I wasn’t and I didn’t see that person,” especially audio. In audio you don’t get to see that. “I can imagine how that would be funny if I had been there.” But that was the limitation I was trying to deal with.

Some people have beaten that limitation. I think Big Jay Oakerson’s audio crowd work albums are really funny, but I was trying to think how to beat that problem. Originally I was going to call the album Five Questions, but I thought Crowd Surfing—there’s just something I like a little better. And it was just to come up with a list of questions that would elicit from the crowd these crazy stories, ‘cuz like I said I think every crowd and every person has a story, so I was like “if I could come up with the perfect five questions…” And I experimented with it a bit as I was doing live dates leading up to it. I was asking different questions, some of which led to less fruitful answers. Like what’s your craziest celebrity encounter, one guy was like “I once thought I saw Bryant Gumbel.” But everybody’s got a crazy sex story, everybody’s got a crazy drug story, not everybody but some people have a crazy police encounter story, so I was like, yeah, if I ask these five or so questions that will elicit answers and then mic the audience it’ll be come less of a “you had to be there situation” and more of a “wow I can’t believe I’m fucking hearing this” situation.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-