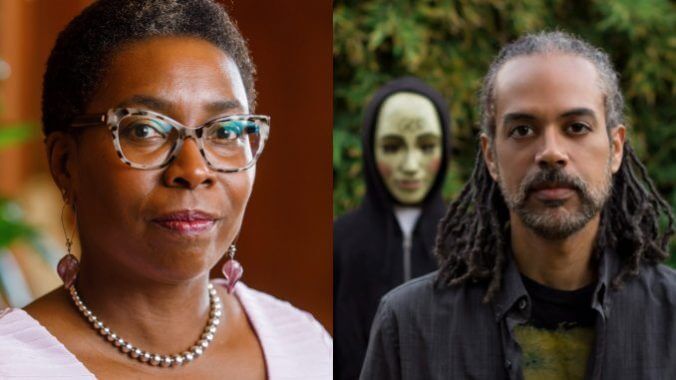

Dismantling The Black Guy Dies First with Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman and Mark H. Harris

Photos courtesy of Texas A&M University, Marketing and Communications / Mark H. Harris

This isn’t horror scholar Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman’s first rodeo.

Not only is her 2011 book Horror Noire: A History of Black American Horror from the 1890s to Present a foundational text on Black horror, Dr. Coleman also produced and appeared in Shudder’s documentary adaptation of it. She’s served as an expert on PBS’s Monstrum with Dr. Emily Zarka to discuss the zombie’s Haitian roots in the show’s “The Origins of the Zombie” episode.

But with the strides taken by Black horror in the decade after her first book’s publication, Dr. Coleman decided to team up with journalist and creator of BlackHorrorMovies.com Mark H. Harris to create an accessible, up-to-date text detailing everything old and new in Black horror: The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar.

Dr. Coleman and Harris were kind enough to squeeze time into their busy pre-book launch schedules to chat with me, individually, about the legacy of comedy in Black horror.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

![]()

Paste Magazine: I wanted to start with the history of “the spook” (a Black character who serves as a frightened comedic relief in contrast to the brave, “rational” white lead) because that’s still very much ingrained into Black representation within a lot of horror movies. I came of age in the ’90s/early-2000s, so Scary Movie was very much part of my adolescence—and it’s a great example of that.

Mark H. Harris: The spook, as a stereotype, has been around for a long time. It has roots in the stereotype that Black people are very superstitious—it goes back to the slavery days when Black people were poked fun at for having these superstitions, whether it be religious beliefs or just a folk-belief in the supernatural. It made its way through the minstrel shows of the 1800s and early 1900s and into cinema when cinema began.

It’s kind of portrayed nowadays as a swaggering type of persona, a bravado kind of approach—but it’s still based in fear. On one hand, it’s smart because they’re not going towards this scary sound. They’re not going to go and get themselves killed. But on the other hand, it does feed into the decade’s old stereotype of Black people being superstitious and scared. And that’s one of the things we unspool in the book.

Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman: When I think about the spook trope, there are two people that come to mind from classic horror cinema: the actor Willie Best and the comedy actor Mantan Moreland. These two Black actors, who performed various “spook” characters, show up to bug their eyes, chatter their teeth, knock their knees, and do a feets-don’t-fail-me-now performance. That’s the spook trope.

Now, what’s really uncomfortable about the trope is that it often turned racist—more so than what I’ve already described. They very much played on racial inferiority, and they stuck. You’ll see those kinds of images appear even outside of the horror genre, on the big and the small screen, in comedies and advertisements.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-