Bushido Baseball: Manga’s Hardcore Take on America’s Favorite Pastime

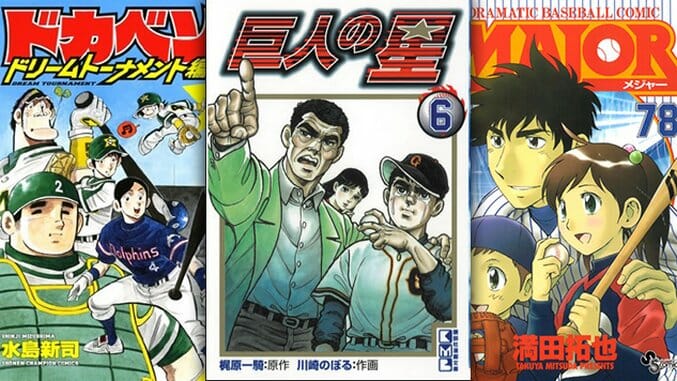

In America, baseball is a pastime. In Japan, it’s a martial art. Yakyu, or Japanese baseball, might look familiar, but don’t be fooled: while the rules are the same, under the surface Japanese baseball is a wildly different game. Just look at baseball manga like Kyojin no Hoshi (Star of the Giants), Dokaben and Major. While American players are judged by individual stats like batting average on on-base percentage, the Japanese focus on team-based plays like the hit and run, the sacrifice bunt and the suicide squeeze. Japanese managers are notoriously controlling; on some teams, players can’t change their socks without permission.

The biggest difference between the two games, however, lies in how the teams practice. In Japan, “spring training” starts in January, when the thermostat hovers around 40 degrees Fahrenheit. During the regular season, players often put in four-hour practices before games even start—extra work is considered a great way to beat Japan’s intense summer heat. At the amateur level, the intensity is even worse. Practices last from six in the morning to nine at night. Coaches hit players with bats and fastballs in order to build endurance. Once, at age 15, former New York Yankees pitcher Hiroki Kuroda was forced to run between the foul poles for four days. He had to do so without drinking a single sip of water.

While lawsuits have softened the culture in recent years, “training hell” remains a major part of Japanese sports culture, romanticized and codified by sports manga for decades. It’s a philosophy based on budo, or the traditional “way of war,” which states that suffering builds strength and character. It’s certainly not unique to baseball; sports are just the latest, most modern incarnation of centuries-old traditions.

A Foundation of Sweat, Tears and Bloody Urine

When baseball first arrived in Japan in the mid-to-late 1800s, players were trained like soldiers. In 1854, the US Naval Commander Matthew Perry forced Japan to open its borders to America. Treaties with other Western countries followed. Soon, foreign advisors arrived to influence Japan’s military and education systems—and they brought comics and baseball with them.

The Japanese adopted both, and in doing so, made each their own. Artists like Rakuten Kitazawa, often referred to as the founding father of manga, fused American comic strips like Richard Felton Outcault’s Yellow Kid with traditional woodblock prints and 13th-century picture scrolls. When American teachers like Horace Wilson and Albert Bates taught their students baseball, the Japanese didn’t quite know what to make of it—team-based recreational sports didn’t exist in Japan—so they turned to what they already knew: the martial arts.

More than any other team sport, baseball plays out as a series of individual encounters, and baseball’s pitcher-vs-batter duels evoke the one-on-one showdowns found in traditional Japanese sports like judo and sumo. Japanese educators lauded baseball’s emphasis on patience, teamwork and self-sacrifice, and like martial arts, considered it an excellent way to teach students about traditional Japanese values like discipline, loyalty and respect.

This was especially true at Ichiko, formally known as The First Higher School of Tokyo, Japan’s first baseball powerhouse. According to Richard Whiting’s book You Gotta Have Wa, many of the students at Ichiko came from samurai families, and the practice routine the school developed was directly based on bushido, or the samurai code. In the military, Japanese soldiers underwent rigorous training in order to strengthen themselves mentally and physically. At Ichiko, the students approached baseball the same way. The baseball stadium became a dojo (literally; once, Ichiko students attacked an American teacher who scaled a stadium wall, claiming that he had defiled a spiritual place) and baseball became an art of war.

As per military tradition, Ichiko’s training regimen was incredibly demanding, and built strength through suffering. Team members lived in isolated dorms, far away from society’s distractions. Practices were so brutal that players peed blood when they were finished. Still, there’s no arguing with the results: in the first official baseball game played between the Americans and the Japanese, the Ichiko team won 29-4.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-