The first thing you see in the just released Halo Infinite multiplayer beta is a short tone setting FMV sequence in which a young woman sneaks through the streets of Covenant occupied London. She is—of course—spotted immediately. Just as she’s about to be killed, an orbital pod drops ahead of her, and out steps her savior: a SPARTAN soldier. This scene is tied together by straining, emotive narration: “What is a SPARTAN? A SPARTAN is a symbol. Hope, where there is none. In times of darkness, we are hope!”

Hope arrives in the form of a fully armored inhuman super soldier unloading an assault rifle into a crowd of gorilla-like aliens actually called Brutes.

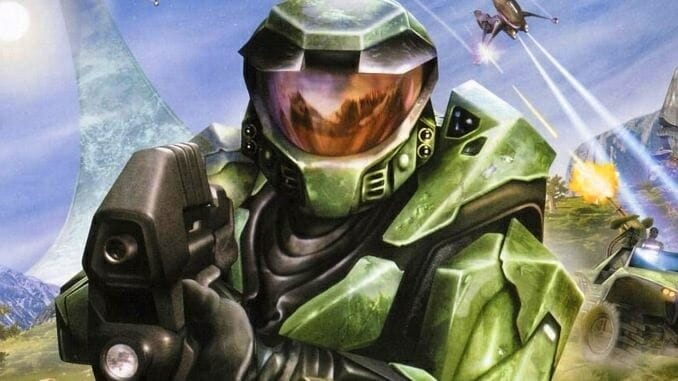

The surprise release of the Infinite multiplayer beta was the centerpiece announcement of Microsoft’s 20th anniversary celebration of the release of the Xbox, and by extension, the release of launch title and killer app Halo: Combat Evolved. The symmetry of this release unintentionally shines a spotlight on the gulf between these two points, raising the question of how on earth the original game—a first person shooter about a space marine killing first aliens, then zombies, then bot —can possibly serve as the foundation for the unstoppable branding machine in which a fake Robocop and the lady inside your computer are the avatars of the indomitable human spirit of hope itself.

To look at the first point: the original Halo is still excellent. Even 20 years on, it’s a classic for a reason. The Pillar of Autumn is an expertly paced opening level, a tutorial for a first timer and a warm handshake for veterans. It slowly unfolds a still impressive combat sandbox, carefully introducing the console players of 2001, and even modern players used to set-piece driven shooting galleries, to a shooter where movement is measured enough that to play at even a casual level is to start to think strategically. Which enemies should I take out first? The grunts rushing from the side, or the shielded Elite at the back? Which weapon should I use? Which type of grenade should I throw? Halo was not the first game to ask these questions of players, even on console, but it was one of the first console shooters to bring all those questions front of mind at all levels of skill.

Nailing this is the reason Halo succeeded. The game runs out of levels halfway through. The story is mostly different artificial intelligences expositing sci-fi concepts so haphazardly you can almost see the overworked developers cutting out levels in real time as the cutscene plays. None of this matters. When an Elite responds to your grenade by rolling away, but you notice his shields are down so switch to your pistol and dispatch him with a headshot? None of that other stuff could possibly matter.

Like Doom before it, with excellent gunplay and a banging soundtrack, Halo was a breakout hit carried entirely on how it feels. And like Doom before it, Halo now had to be a franchise. A series of icons and connotations that by virtue of popularity must now be converted into the building blocks for a brand that can be sold and resold in perpetuity. This in itself is not unique or egregious, it’s simply how corporate art is produced. But Halo sat in a strange position, being neither a purely evocative blank slate nor a rich and textured world, and Microsoft dragged a reluctant Bungie into fleshing out a vague universe with a novel before the game was on shelves and its success assured.

This process led to a narrative framework that pulled patchwork out of ‘80s media. Master Chief was somewhere between Robocop and Judge Dredd, a kidnapped child turned into a supersoldier to violently suppress worker rebellions. The marines were, like approximately half of all videogames ever produced, lifted wholesale from Aliens, parodies of masculine bravado that died screaming in terror. Yet they sat next to characters like Sergeant Johnson and Captain Keyes, deeply earnest portrayals of military cool guys, dropping one-liners and heroic sacrifices in turn. Halo was one of many nerd objects of its era that relished in the end of history; that understood Starship Troopers was a satire, but also thought it was cool, seeing no shred of irony or contradiction between those two ideas.

With such an uneven and carbon dated starting point, it is little wonder the following 20 years of Halo The Brand have been weird, but special mention must be paid to just how buck wild it has become. Cortana is a fully sentient AI clone of Master Chief’s surrogate mother, scientist and war criminal Dr. Halsey, who kidnapped hundreds of children and turned them into supersoldiers for a fascist superstate. She stays activated with Chief so long her artificial brain begins to decay, expressed in game through a deeply misguided romance plot between the two. If you’ve not played the games, she’s naked this whole time. It is only after this that Microsoft decided to put her in literally everyone’s search bar.

Every franchise changes its meaning over time. Culture shifts, and corporations target new demographics in new contexts. Halo is not even alone in its predicament of having to re-calibrate for a modern audience a series whose audience and creation are both so muddled it’s impossible to detangle left-leaning parody from awestruck depictions of fascist heroism: Warhammer 40k has YA novels now. Yet the specific choices made in what we’ve seen of Infinite serve only to highlight how special Halo is in its incoherence. It’s a weird game made in a time when teams were small enough that their interests and contradictions could live on the screen for all to see. Its narrative and thematic ideas didn’t have to cohere: they were the skin for the best first person shooter anyone with a gamepad had ever played.

Microsoft desperately wants to sell Infinite as a throwback, a return not just to form but to how you felt in 2001. Master Chief is back. You’re exploring a Halo. Every developer says “combat sandbox” every 10 seconds to let you know that we know. But the attempt can only underline how far out of reach the past is, and how we don’t need to wait for the new thing to recapture the glory. It’s still worth visiting Halo every once in a while.

Jackson Tyler is an nb critic and podcaster at Abnormal Mapping. They’re always tweeting at @headfallsoff.