Murder mysteries seem like great fodder for board games. So why is it so hard to translate the experience of a great mystery novel or film to the tabletop?

Suspects is the latest game to claim inspiration from the Queen of Mystery herself, Agatha Christie, who is generally acknowledged as the best-selling fiction writer in history. Rather than using any of her characters or stories, however, Suspects tries to mimic her style, in the settings of the murders, in the sorts of clues available to players, and in the text on the various cards that constitute each case. Imitating Christie’s style isn’t hard, but her genius lay in how she constructed her crimes, and had her detectives, mostly the fatuous Hercule Poirot (and his little grey cells) and the unassuming Miss Jane Marple, come to their conclusions. Suspects tries, but ultimately it falls short.

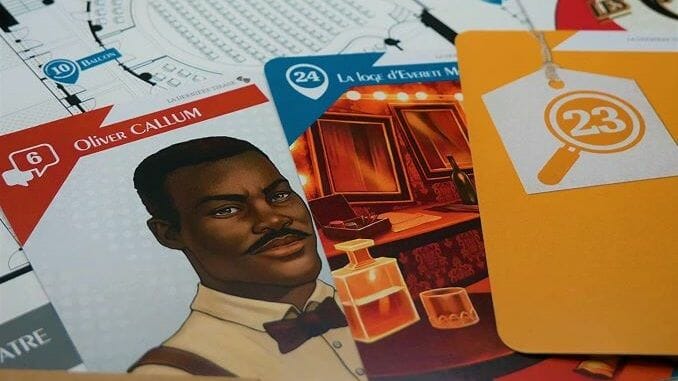

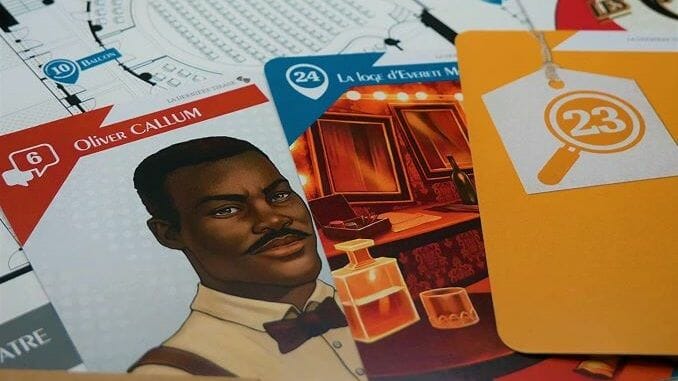

Suspects is a cooperative game that lists a playing time of 60-90 minutes, but it’s playable as a solo game, and the time it takes to complete one case really depends on the player count and, more so, how much time you spend discussing the clues. The base game comes with three cases, with another box including three more to follow, and each case is completely independent in components and content. There’s a murder, and you get a map and a deck of cards. You may only look at a card when you encounter its number somewhere—in the setup, on the map, or on another card. Each card can represent a location to search, which may give you two or three more card numbers; a person to interrogate, which can give you a whole bunch of additional numbers; or an object that might be a direct clue or something you use to identify a suspect. The card decks are all about 50-55 cards thick, and many cards are red herrings or just not useful (by design).

Each case is structured more or less the same way—you get a sheet with a brief story and five or six questions you need to answer, including who the killer is. You’ll get about four to six suspects, a fixed setting like a large hotel or a theater, and at least one card that you will need to find so you can compare it to various other cards in the deck, such as comparing Suspects’ shoe sizes to a shoeprint you found. The order in which you uncover the clues doesn’t necessarily matter, although the game’s scoring system gives you a few more points if you solve the using fewer cards—not that this matters much, since the main enjoyment in any cooperative mystery game, like the Exit! games or Chronicles of Crime, comes down to whether you solve the mystery or not. When you think you’ve solved it, you open the small envelope for that case, and read through the answers to all of the case’s questions, each of which clearly identifies the cards that showed the relevant evidence.

The concept is fine, but the writing is where Suspects falls short. One case’s resolution revolves around someone hearing something through a wall, which you are supposed to guess because a card refers to the walls being “paper thin.” That’s way too big an assumption to ask players to make, in my opinion, and much flimsier than the evidence you’d find in the resolution to a Christie story, or a Sayers or a Marsh or any of the golden-age mystery writers’ works. The visual clues are far more effective, while the text clues tend to be where the cases break down. The third case seems to be missing a clue somewhere; even after reading all of the cards, and going through them a second time to look for that missing link, I couldn’t find it anywhere.

As a result, Suspects plays a bit like those old 10-minute mysteries you used to hear or read as kids, but with more packaging around them. The framework of a good game is here, although in the end I’m not sure there’s anything that would distinguish it from any other mystery title. It just needs better writing to get there.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.