An Interview with Poet D.A. Powell: “Whatever You Do in Your Art Has Ramifications”

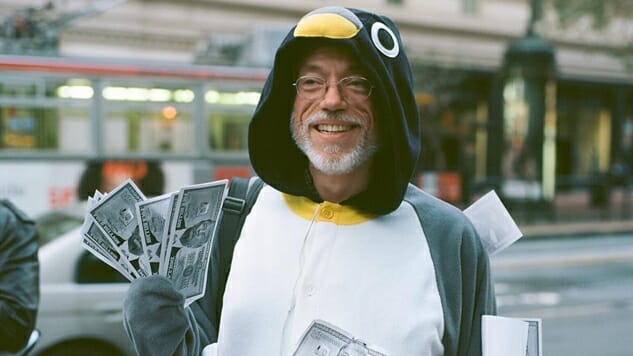

Photo Provided by D.A. Powell

Last week, the 50th annual Associated Writing Programs (AWP) Conference kicked off in Washington D.C. As of a few months ago, California-based author D.A. Powell—whose book Useless Landscape, or A Guide for Boys (2012) won the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry—wasn’t planning on attending. Donald Trump changed his mind.

Photo by Jeff Malet, maletphoto.com

Once [Trump] took office and began to sign executive orders banning Muslims and immigrants, okaying discrimination against LGBTQ people, and dismantling the Environmental Protections Agency, I felt it was my duty as an American to show up and be counted,” he explained. “I’ll be marching with thousands of other writers on Friday up to Capitol Hill, where we’ll deliver messages to our respective Congress members.”

Art’s overlap with resistance has become increasingly apparent in recent months. Powell was also a participant in Bay Area Writers Resist—one of 100 events organized on Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday to showcase the role of writing in upholding democracy. The aforementioned march is part of the Write Our Democracy movement that spun out of those events. I caught up with Powell to discuss the relationship between politics and poetry.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Paste: In an earlier email, you wrote to me: “I’m less of a message-driven writer, although much of my work is described as political.” With that in mind, how do you see your writing fitting into the resistance, if at all?

D.A. Powell: It should be the least political thing to do—to write about one’s own life and experience of the world. But as a gay man, as someone living with HIV, I find that my life story gets co-opted or erased by others if I don’t tell it myself. To write my own life seems to be an upstream battle in this society. And there are many others who experience the world in the same way, who don’t have the impetus to write, or the tools to write, or the access or time or whatever it is. The crazy thing is that when I started writing poetry, I thought: I’m doing it for myself, for my own entertainment, to fuck off, to waste time.

When your work starts reaching an audience, you feel bound by their expectations—I guess in the same that a politician would or should feel bound by the expectations of their constituency. As a poet you have a constituency, albeit a very small one. You don’t have to always play to them, but at least respect their existence and be aware that whatever you do in your art has ramifications.

Paste: Can you talk a little bit more about those ramifications? How much do you think about art in terms of a call to action—wanting to change someone’s mind or drive them to do something? Or is art inherently separate from outcome?

Powell: I think of it as separate from outcome, and yet it does have outcome, a ripple effect, consequences. The most recent example in my own work is that I was writing during the Michael Brown investigation and reading about how [after his murder] his body was not moved—there was no attempt at CPR, no life-saving measures of any kind. He simply laid in the street like the carcass of an animal.

I found myself coming back to that image and having to weigh: What is my responsibility? How can I talk about this as a white man in society without taking the spotlight from some other writer whose life experience is closer to Michael Brown’s?

Ultimately, I ended up with a poem (Long Night Full Moon) that wasn’t obviously about Michael Brown, but was acknowledging this illness in society that causes these kinds of deaths and these kinds of justifications of systemic racism. We can’t not talk about it.

Paste: The question of what stories are yours to tell—that reminds me of something else you said in your email, which was about affirming and recognizing voices that might be stifled. Is that sometimes done through avenues other than writing? Through organizing or teaching?

Powell: Absolutely through teaching. And I do a lot of editing work and contest judging and I’m always trying to use that position to correct what the poetry landscape sometimes looks like, which is very middle class and very academic. So I’m always looking for voices that are coming from real-world experience, real-world issues. And maybe voices that aren’t being represented.

I mean, I’m also looking for good work. You can’t leave one part out of the equation. But I always feel good when I’ve gotten to a place where the best manuscript in the batch is something like Telepathologies, which is coming out next month, by Cortney Lamar Charleston. And he’s writing about the attack on the Mother Emanuel Church in South Carolina, he’s writing about Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin. He’s addressing all the things that I think poetry needs to address now—and in a way that is smart, authentic, necessary and urgent.

I got an email just a couple days ago from Daniel Handler (Lemony Snicket) and he said: I’m just reading this new book you chose by Cortney Lamar Charleston. Can you get in touch with him? I’d love to read more of his poetry. That’s really what my job is in terms of being a teacher and a poet: to bring these other voices and help to change the sound of the orchestra.

Paste: I’ve been talking to a lot of writers—not just poets—about art and resistance. I feel like in 2016 there was so much more of an explicit, mainstream acknowledgement of the importance of poetry specifically. I’m curious to hear your two cents on why the form matters.

Powell: I always feel like when people are asking that big question—does poetry matter?—It’s sort of a non-issue for me and most people that write and read and enjoy poetry. It’s like: It matters if it matters. If you respond to it, it’s important. Poetry is not the same as rock ‘n roll. It’s not a popular art in that regard. It’s a little bit more like folk music—best heard in small groups, in quiet places, to an audience that wants an alternative to blockbuster motion pictures, an alternative to sell-out concert halls. Poetry almost doesn’t work in mass quantity.

Every once in a while there is a poem that sort of catches fire. Recently there was a wonderful poem by Maggie Smith called “Good Bones” that a lot of people have been reading and passing along to each other. But that’s just it. It goes person to person. It doesn’t help to have Oprah pick a poem. [laughs] By design it’s not an art form for the masses. And that’s alright.

Paste: At Writers Resist, you didn’t read poetry though, right? You read a prose piece.

Powell: Yes. There’s a poem by June Jordan. She’s writing about New York and she gets to this point where she’s describing the landscape and she says: “And that was day we conquered the air / with 100,000 tons of garbage.” It actually breaks form. Then she ends with a couplet: “No rhyme can be said / where reason has fled.” That’s how I feel at the moment.

So I wrote a prose piece [for Writers Resist] and read it. It was about Flannery O’Connor. [She] used to keep a spiritual diary for a brief time in her life when she was trying to be a better Christian. And there’s a page missing and on the next page she begins: “Tore the last thing out. It was worthy of me all right; but not worthy of what I ought to be.”

I feel like Donald Trump is such a page that we should be ready to rip out of the history books. His policies are detrimental to the core values of American society. He’s violating the narrative of who we are.

Alyssa Oursler has written for the Los Angeles Review of Books, USA Today, Popular Science and more. You can find her on Twitter: @alyssaoursler.