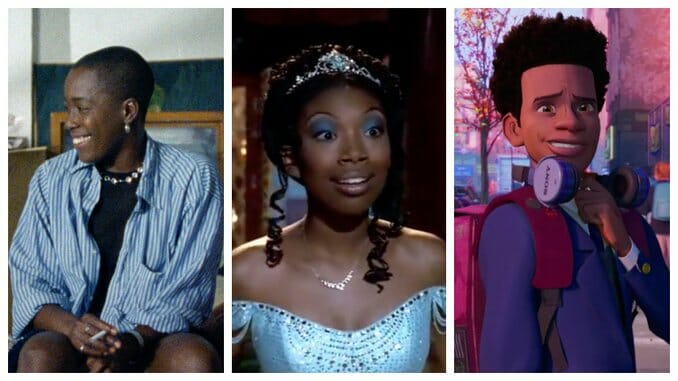

10 Movies Celebrating Black Joy

It’s Black History Month! Black and non-Black people alike typically spend this month in a number of generative ways: Reading literature by Black authors, patronizing Black-owned businesses and reinforcing an interest in Black life by consuming art that centers Black people. While the intention behind the latter effort can be good, streaming platforms sometimes push television and film titles that falsely suggest that the crux of Black life is hinged on suffering. Trauma Porn February Film Nights are not the same as educating oneself about the dynamism of Black experiences or making a personal commitment to care about Black people year-round. Therefore, it is important people take time to familiarize themselves with and also normalize depictions of Black people experiencing joy, levity and pleasure. That’s why we’re here. It’s time for movies about Black joy.

Rewatching Roots, 12 Years a Slave or any other number of projects that masterfully capture the cruelty of generational dehumanization and chattel slavery is not wholly misguided. These aspects of Black history continue to leave an imprint on Black life and still shape the socio-economic treatment of members of the Black diaspora worldwide. However, by sequestering visual representations of Black experiences to cinematic pantheons that are thematically linked to pain, abuse and interpersonal harm, people also begin to associate Black life with the discomfort of witnessing Black strife. This pattern of cognitively associating Black people with stories that arouse discomfort and upset is complicated. On one hand, it is useful because the racism Black people experience on a daily basis is upsetting and uncomfortable. Films that capture that strife visually name and attest to the reality of those experiences for Black and non-Black audiences. But if stories in which Black people suffer are deemed authentically Black because of the suffering or because of the benevolence of white characters, the notion that Black people are agents within their own insular moments of revelatory play, happiness and silliness will continue to feel like an anomaly.

In the spirit of dismantling the false equivocation of Blackness and strife, the reduction of Black experiences to a singular Black experience and the spectacularization of Black joy here are 10 films you can watch at any point in the year to honor the emotional dynamism of Black people.

Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit (1993)

Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit is a cherished Black classic that is somehow always on television. I own the film on VHS and have never seen the original. This musical sequel follows Sister Mary Clarence (Whoopi Goldberg) as she is tasked to shape a group of ragtag San Franciscan youth into a competitive gospel choir and save their underfunded school. Pre-Miseducation Lauryn Hill plays Rita, a young Black girl who loves to sing but is apprehensive to share her passion with her unapproving mother. The film is revelatory and joyful—joyful not only because its ensemble cast features fresh-faced Black youth and other youth of color navigating quintessential challenges of coming-of-age through the power of sing-song, but because their particular struggles are captured in a way that honors their experiences without falling into the common traps of fetishistic, narratively voyeuristic underprivileged youth movies a-la Freedom Writers, The Blind Side, etc. The film radiates with the luminescence of early ‘90s Afrocentrism and hip-hop culture. The heartwarming post-credit scene in which the entire cast (hello, Jennifer Love Hewitt and Mr. Noodle from Sesame Street) sings an original arrangement of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” is worth the price of entry alone.

The Watermelon Woman (1996)

A narrative film that incorporates nonfiction elements (such as talking heads including real academics), The Watermelon Woman blurs the line between Cheryl, the character, and the real-life Cheryl who exists behind the camera. The title refers to a fictional black actress by the name of Faye Richards—credited in films as “the watermelon woman”—who played the stereotypical “mammy” role in the 1930s. Part of the film follows Cheryl, a documentary filmmaker, as she learns more about Richards, while the other part follows her love life, as she starts dating a white woman, Diana (Guinevere Turner). The latter becomes a huge point of contention in Cheryl’s life. Her fellow black lesbian friends take issue with Cheryl and Diana’s interracial relationship—something Dunye wishes there were more discussion around.

“I was living it and I wanted to have a conversation about it,” Dunye says, referencing her offscreen relationship with The Watermelon Woman producer Alexandra Juhasz, a white woman. “We notice interracial relationships all over the map but nobody sort of talks about them. I think about white philanthropy. We’re having a huge discussion about it now, with Black Lives Matter, and how non-black people can get involved.”

For a film with such a strong outsider narrative, it’s worth noting that The Watermelon Woman doesn’t take on the particularly tragic tone opted for in many queer films. It reflects the ongoing “need to push storytelling,” in Dunye’s own words, but its lightheartedness echoes that of fellow ’90s queer film Go Fish (also starring Guinevere Turner). And as educational as it is about race and gender politics, The Watermelon Woman also carries itself with the charm and lifelike quality of a Linklater film. Twenty years later, “it’s fun, it’s funny, it’s entertaining, you have a good time,” Dunye says. “And you walk away with something. And that’s what I want people to do.” —Kristen Yonsoo Kim

Sylvie’s Love (2020)

Between her roles in independent films like Nia DaCosta’s Little Woods and bigger-budget appearances as a Valkyrie in the MCU, Tessa Thompson knows how to pick a project. With Sylvie’s Love, Thompson has demonstrated that she also knows how to superbly executive produce her own work. Thompson plays Sylvie—the daughter of a record-shop owner in 1950s Harlem—in the film, which captures the romance that develops between the high society character and Robert, a saxophonist portrayed by Nnamdi Asomugha. While Sylvie’s Love may appear to be a mid-20th century romance in the vein of If Beale Street Could Talk or Paris Blues, the title of this 2020 release has a double effect: Sylvie’s love encapsulates the affection she develops for Robert despite their class differences and the disapproval of her mother, but also to Sylvie’s dream of being a television producer. Sylvie manages her vocational aspirations alongside social pressures to make her romantic life her top priority in pre-second wave feminism America. But Sylvie’s Love succeeds on multiple fronts: It celebrates the sexual agency of its Black women, depicts the ambition of a Black woman in the workplace and manages to honor quotidian Black life in the 1960s without centering white vitriol. Also, Bridgerton fans will be glad to know that Regé-Jean Page, The Duke of Hastings himself, plays Chico Sweetney—a smooth-talking, debonair jazz musician.

Crooklyn (1993)

Crooklyn won’t go down in Lee’s filmography as a thematically important achievement, but it still might be his most heartwarming work to date. This makes sense, since it’s pretty much an autobiographical film about growing up in 1970s Brooklyn, communicated through the rosiest of rose-colored glasses. Sure, he takes on some serious issues, like the drug use that permeated his neighborhood, but it’s mostly a love letter to his youth, giving back to the borough that defined him as an artist and a person. Zelda Harris is downright adorable as Troy, a precocious nine-year-old firecracker in 1973 who’s beginning to truly discover her home and how it connects to her family, which is made up of her four siblings, her teacher mother (Alfre Woodard) and her jazz musician father (Delroy Lindo). The exuberant color scheme makes Brooklyn look like a child’s dream, full of hidden wonders, placing the audience squarely in Troy’s point-of-view. Crooklyn also holds the distinction of employing the most surreal application of Lee’s trademark “floating” tracking shot.—Oktay Ege Kozak

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-