Best of Criterion’s New Releases, February 2020

Each month, Paste brings you a look at the best new selections from the Criterion Collection. Much beloved by casual fans and cinephiles alike, Criterion has for over three decades presented special editions of important classic and contemporary films. You can explore the complete collection here.

In the meantime, because chances are you may be looking for something to give the discerning (raises pinkie) cinephile this month, find all of our Criterion picks here, check out some of our favorite new releases from February, and, hey, maybe sign up for Criterion’s Criterion Channel to stream many of the titles we talk about here.

Teorema

Teorema

Year: 1968

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Stars: Terence Stamp, Silvana Mangano, Massimo Girotti, Anne Wiazemsky, Andre Jose Cruz Soublette, Laura Betti, Ninetto Davoli

Genre: Drama, Comedy

Rating: NR

Runtime: 98 minutes

Little is said throughout Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema; in an interview included with Criterion’s edition, when asked about the experience playing the enigmatic Visitor, the ethereal man who effortlessly seduces a whole hyper-wealthy Milanese family from son to sire—absolutely slobbered over by Pasolini and cinematographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini’s gaze—Terence Stamp describes his relationship with the Italian director as pretty much non-existent. At best. Ignoring the actor throughout most of filming, Pasolini encouraged Stamp, by default, to define whomever, or whatever, the Visitor was supposed to be. Similarly, silence and languorously sexy scenes greet the viewer, leaving us to suss out not only how deeply the emptiness of this extremely rich family can go, but whether this otherworldly lothario is a force of good or evil. Or neither, just a physical force of Marxist change, pushing the lowly housekeeper (Laura Betti) toward beatification while deconstructing the bourgeoisie dynastic unit until it dissolves into a final, primal scream before meeting the void. In the silence we grow horny. Terence, stamp on my neck. —Dom Sinacola

Roma

Roma

Year: 2018

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Stars: Yalitza Aparicio, Marina de Tavira, Marco Graf, Nancy García García, Diego Cortina Autrey, Carlos Peralta

Genre: Drama

Rating: R

Runtime: 135 minutes

Alfonso Cuarón’s love for Libo, the nanny and housekeeper who worked for his family and cared for him since he was a newborn, is so immense that nothing less than state-of-the-art craftsmanship would suffice for shooting Roma. This isn’t simply foreign language arthouse cinema, it’s Cuarón’s loving ode to the woman who raised him. (“Raised” may be an exaggeration. But by his own account, he and his siblings called Libo mamá, so take that as you will.) At a glance, bringing an Alexa65 to an intimate portrait of domesticity, family and sociopolitical turmoil in 1970s Mexico City feels like using a tank to swat a fly, but Cuarón’s insistence on using the best technology to tell Libo’s story—which is his story, too—speaks volumes of his feelings for her. This is not simply a film about the help, nor an exploitation of class, of work, of womanhood. It’s a loving tribute to Libo’s memory, and to the memory of women like her. To an era of Mexico’s history, and to Cuarón’s own boyhood. He could’ve captured these experiences, these sensations, any number of ways, but Roma functions as a monument in motion: It’s a piece of great archaeological importance to Cuarón. Here, he immortalizes the foundation of who he is as an artist in black and white, a color scheme that both belies and accentuates the depth of his protagonist Cleo’s (Yalitza Aparicio) story. Roma is a subtle film. Roma is a bold film. Most of all Roma is a personal film, a reenactment of lives lived made on the grandest stage possible. —Andy Crump

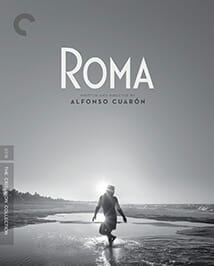

Antonio Gaudí

Antonio Gaudí

Year: 1984

Director: Hiroshi Teshigahara

Genre: Documentary

Rating: NR

Runtime: 72 minutes

Those who know nothing about Spanish architect Antonio Gaudí will find little edification amongst the lushly photographed edifices in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s lovely, shapeless doc. There is no guiding voiceover, only a few talking heads discussing the man within the bounds of news reports or historical context, a few blunt and scratchy clips of Gaudi in public, of his funeral, of standing in the epic shadows of what he’s designed. Otherwise, Antonio Gaudí visits the architect’s many iconic buildings, cinematographers Junichi Segawa, Ryu Segawa and Yoshikazu Yanagida accompanying Teshigahara to capture the wildly imaginative, otherworldly creations in conversation with the changing urban landscape around them. Perspectives shift imperceptibly, from the onlooker on the ground to seemingly that of the buildings themselves, that of gods looking down on the implacable fray below. The tour culminates in a lavish skimming of Gaudí’s opus, the Sagrada Familia cathedral in Barcelona, a few climactic minutes that are so sublime one’s immediately pulled from the reverie the film’s spent an hour conjuring, woken to the sheer majesty of what Gaudi once accomplished. And yet, what of the men who died in building this? What of its seemingly precarious existence, the ephemeral nature of all of this, of all of Gaudi’s art? In honoring the foundational effort of this one man, the director leaves us with the notion that it’s a miracle it exists at all, that it all could crumble—its discussion with the earth on which it rests gone silent—nothing more than a dream within a dream. —Dom Sinacola

Paris Is Burning

Paris Is Burning

Year: 1991

Director: Jennie Livingston

Genre: Documentary

Rating: R

Runtime: 76 minutes

Madonna’s “voguing” phase has nothing on—that is, took everything from—the drag scene of 1980s New York City chronicled in this vibrant doc. Delving into the subculture of fierce, catwalk-styled posing and the clubs in which it thrived, Jennie Livingston depicts the less-than-glamorous realities of life as a drag queen before RuPaul was mainstream: issues of gender and sexual identity, race, bigotry and hate, HIV/AIDS, poverty, crime—theft is a commonplace means by which these would-be “Legends” seek a desired end: transformation. Named after one of the underground balls in which its subjects find a sense of family—in “houses,” no less—Paris Is Burning is a joyous affair, and a curiously meta celebration of what it means “to be real.” —Amanda Schurr

Three Fantastic Journeys by Karel Zeman (Journey to the Beginning of Time; Invention for Destruction; The Fabulous Baron Muchausen)

Three Fantastic Journeys by Karel Zeman (Journey to the Beginning of Time; Invention for Destruction; The Fabulous Baron Muchausen)

Year: 1955; 1958; 1962

Director: Karel Zeman

Genre: Action & Adventure; Science Fiction & Fantasy

Rating: NR

Runtime: 93 minutes; 84 minutes; 87 minutes

During one of the interviews in Criterion’s wondrous box set collecting three of Czech filmmaker and “fantasist” Karel Zeman’s most influential features, animator John Stevenson describes how a movie’s subpar photorealistic special effects can do the opposite and take us out of the fantasy, but art and artifice that’s deliberately abstract or imperfect can open up our imaginations. Similarly, Zeman’s liberal use of stop-motion, cell animation, cutouts, miniatures, puppets and forced perspective, sometimes all composited within the same shot, creates a tactile dream world that compliments his boundless desire to take his audience on adventures they’ve never experienced before.

We begin with Journey to the Beginning of Time, a fun and informative edutainment piece for young children about four grade school friends literally sailing backwards in time to meet and identify various dinosaurs. Then we move on to Invention of Destruction, a love letter to Jules Verne, with flat black and white cinematography and design that’s meant to look like a 19th century storybook come to life. Finally, we’re spirited away to The Fabulous Baron Munchausen, an obvious inspiration to Terry Gilliam’s own take on the sprightly adventurer. Zeman’s series of increasingly whimsical tales displays all the tricks in his arsenal to create a kind of lucid dream that lingers like a far away memory.

Criterion’s restoration cleans up the films as much as possible for crisp HD presentations, but still allow for various blemishes in the composite shots, thankfully retaining the original art and integrity of Zeman’s work. The extras are bountiful, from the aforementioned animator interviews, to four of Zeman’s early animation shorts, but the real treat is a feature-length documentary about the master himself, with interviews with Gilliam and Tim Burton. The set’s packaging, too, matches Zeman’s playful nature, offering pop-up models for every film. —Oktay Ege Kozak