Best of Criterion’s New Releases, June and July 2020

Each month (or, in this case, every two months or so), Paste brings you a look at the best new selections from the Criterion Collection. Much beloved by casual fans and cinephiles alike, Criterion has for over three decades presented special editions of important classic and contemporary films. You can explore the complete collection here.

In the meantime, because chances are you may be looking for something, anything, to discover, find all of our Criterion picks here, check out some of our favorite new releases from June and July, and, hey, since many of us have a lot more time on our hands, maybe sign up for Criterion’s Criterion Channel to stream many of the titles we talk about here.

Bruce Lee: His Greatest Hits Years: 1971-1978

Years: 1971-1978

Directors: Lo Wei, Bruce Lee, Robert Clouse

Genre: Action & Adventure, Martial Arts

Why something remains current in pop culture consciousness—what it takes to remain present decades later, and what actual aspects “stick”—can feel impossible to pin down. Heck, even the vessel that holds or refreshes the reference can shift. Up until, oh, 1991, the image of playing chess against the personification of death was firmly referentially rooted in Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 classic, The Seventh Seal. (That image in turn had plenty of precursors in art, including Swedish painter Albertus Pictor’s depiction way back in the 1400s.) But in 1991, a little sequel called Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey sauntered up and took the torch, and, now, nearly 30 years later, modern awareness of a classic image of inevitable mortality inescapably resides with Keanu and Alex as much as it does with Ingmar.

Which brings us to Bruce Lee. Even if you have never seen his films. Even if you know nothing of his story, you probably know his gestures. You definitely know his presence. The thumb-nose rub. From The Matrix (Keanu is everywhere!) to countless films both cheesy and earnest, the spirit of Lee and his sheer energy and fighting style have seeped into as many mediums and arguably more moments than Bergman. And no, I’m not discounting Bergman’s extraordinary influence on filmmaking as a whole, but if you want to really bone up on that oeuvre, it’s going to require a lot more time and investment than Criterion’s new release of Bruce Lee: The Greatest Hits. (No worries on the Bergman—Criterion’s got you covered with an amazing 39-film set.)

As this set shows, Lee both needed and has earned the “Criterion treatment.” Bruce Lee: The Greatest Hits includes seven discs (five films and two discs of supplemental material) with 4K digital restorations of The Big Boss, First of Fury, The Way of the Dragon and Game of Death, and a 2K digital restoration of the 99-minute 1973 theatrical release of Enter the Dragon, and audio commentaries, documentaries and interviews abound. Again, Lee’s influence has long been recognized and his legacy closely examined—after all, what other individual else has their own “-ploitation” subgenre? (The collection features a discussion of Bruceploitation films with author Grady Hendrix, along with a number of trailers from films in the subgenre.)

Though we may never know what it will take for a person to leave a lasting impression on the zeitgeist, Bruce Lee: The Greatest Hits will remind us how Bruce Lee left his. —Michael Burgin

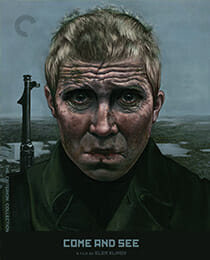

Come and See Year: 1985

Year: 1985

Director: Elem Klimov

Stars: Aleksei Kravchenko, Olga Mironova, Liubomiras Laucevicius, Vladas Bagdonas,

Genre: Drama, War

Runtime: 146 minutes

Elem Klimov’s film is the war movie as expressionist horror, a diorama of violence and dreadful symbolism that’s also a cruel coming-of-age spectacle. Perhaps Klimov could only comprehend the genocidal reality of the Nazi war machine storming Belorussia through this hallucination of sound and imagery: corpse-piles attracting clouds of flies, dairy cows machine-gunned by tracers at dusk, forest bombing raids that leave the lead character’s (and the film’s) aural faculties muffled. Though we’re witness to atrocities, including a climactic annihilation of a Belorussian village that may be the single most effective anti-war scene in all cinema, the damage done to young hero Flyora (Aleksei Kravchenko) is what’s most unforgettable, as he enters the picture fresh-faced and idealistic and leaves it withered and hollow. The title is taken from a line in the Book of Revelation; the epic terror implied in the biblical quotation is absolutely fitting. If the purpose of a war movie is to make war appear absolutely and totally harrowing, then Come and See might be the greatest ever made. —Brogan Morris

Taste of Cherry Year: 1997

Year: 1997

Director: Abbas Kiarostami

Stars: Homayoun Ershadi

Genre: Drama

Runtime: 100 minutes

An existential tone poem of exasperating pace and deliberation, Taste of Cherry takes the long way in almost every conceivable fashion. Kiarostami stages a bare minimum of plot in his favorite setting—a moving vehicle—his middle-aged protagonist driving around the dusty roads of the Northern Iranian village of Koker. Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), a Range Rover-driving stoic, surveys stranger after stranger, inviting a few into his car to discuss a low-effort, high-paying job. He needs help committing suicide.

The ensuing conversations are uncomfortable, philosophical, layered, sometimes labored. When Kiarostami isn’t taking viewers on a physical journey of unflinching confrontation, he’s likewise keeping us at a literal distance—behind windows and from wide, curiously flat shots, the isolation of the car contrasted with expansive landscapes of industrial machinery. Mr. Badii’s voice is at times obscured behind glass; we strain to see him through semi-sheer curtains or a ticket booth—we don’t even get a first name. We are denied the slightest of intimacy, determinacy or logic. In turn, there’s something transient and yet immemorial to Taste of Cherry, a confounding, transcendental bridge between extremes and experiences, cultures and politics, passenger and driver, viewer and Kiarostami himself, between our respective unknowns. —Amanda Schurr

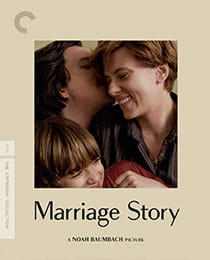

Marriage Story Year: 2019

Year: 2019

Director: Noah Baumbach

Stars: Scarlett Johansson, Adam Driver, Azhy Robertson, Laura Dern, Alan Alda, Ray Liotta, Julie Hagerty, Merritt Wever

Genre: Drama, Comedy

Runtime: 136 minutes

The way that Adam Driver ends “Being Alive,” which his character in Marriage Story has just sung in full (including dialogue asides from Company’s lead’s friends), is like watching him drain what’s left of his spirit out onto the floor, in front of his small audience (which includes us). The performance starts off kind of goofy, the uninvited theater kid taking the reins to sing one of Broadway’s greatest showstoppers, but then, in another aside, he says, “Want something… want something…” He begins to get it. He begins to understand the weight of life, the dissatisfaction of squandered intimacy and what it might mean to finally become an adult: to embrace all those contradictions, all that alienation and loneliness. He takes a deep exhalation after the final notes, after the final belt; he finally realizes he’s got to grow up, take down his old life, make something new. It’s a lot like living on the Internet these days; the impossibility of crafting an “authentic self,” negligible the term may be, is compounded by a cultural landscape that refuses to admit that “authenticity” is as inauthentic a performance as anything else. Working through identities is painful and ugly. Arguably, we’re all working through how to be ourselves in relation to those around us. And that’s what Bobby, the 35-year-old at the center of Stephen Sondheim’s 1970 musical Company, is doing. The scene forces the viewer to make connections about their humanity, the art they’re experiencing, and the ever deadening world in which it all exists. Charlie grabs the microphone, drained, realizing that he has to figure out what he has to do next, to re-put his life together again. All of us, we’re putting it together too. Or trying, at least. That counts for something. —Kyle Turner

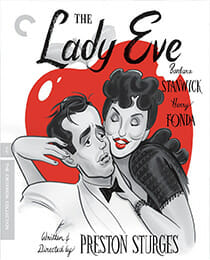

The Lady Eve Year: 1941

Year: 1941

Director: Preston Sturges

Stars: Barbara Stanwyck, Henry Fonda, Charles Coburn, Eugene Pallette, William Demarest

Genre: Comedy, Romance

Runtime: 93 minutes

One of director Preston Sturges’ defining films, The Lady Eve centers on a beautiful con woman (Barbara Stanwyck) determined to catch the affections (read: the inheritance) of a naive rich boy (Henry Fonda) just recently arrived from a year-long excursion to the Amazon. In a nice twist from the battle-of-the-sexes formula that characterized countless rom-com romps of the era, The Lady Eve finds traditional gender roles reversed, with Stanwyck’s Jean Harrington acting as the dominant, sexual aggressor and Fonda’s sweet but clueless Charles Pike serving as the passive object of desire. Packed with secret identities and enough broad farce to rival a Shakespeare play, The Lady Eve stands as a stone-cold American classic. —Mark Rozeman

Tokyo Olympiad Year: 1965

Year: 1965

Director: Kon Ichikawa

Genre: Documentary

Runtime: 168 minutes

So: You’re an Olympics watcher, and Tokyo 2020 got cut because of the COVID-19 outbreak. You’re probably pretty bummed. Good news! You can watch Kon Ichikawa’s 1965 stunner Tokyo Olympiad instead, a documentary ostensibly made to cover the 1964 Summer Olympics but engineered by Ichikawa as a masterwork of technique and a testament to the human spirit at the sporting event’s core. Japan’s government also saw the movie as an opportunity to put the country back on the world stage, following the devastation wrought on its shores during World War II. Japanese officials weren’t happy with Ichikawa’s work—they asked for something with a more straightforwardly documentarian bent, akin to journalism instead of art—but they also couldn’t make Ichikawa do a damn thing to change Tokyo Olympiad because everybody had left by the time he finished, and so decades later his towering achievement remains intact for all to bathe in its portrait of glory and victory and, yes, even defeat.

The latter element appears more important to Ichikawa than the former two: He focuses on the losers more so than the winners, arguing in so doing that to come in second or third in the Olympics may be painful, but it’s still an accomplishment worth commemorating. Very few people ever reach Olympian peaks of performance, and even with countries ranging from the United States, to England, to South Korea, to Ghana, to Cameroon, to the Netherlands, to Nepal, to Italy all assembling under the banner of Olympic sport, mankind still feels underrepresented in terms of sheer numbers. (Watching the athletes march onto the stadium field is, in fact, quite like watching the Council of Elrond in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, but with considerably more racial diversity and fewer orcs.)

“Humans dream only once every four years,” Ichiro Mikuni, the picture’s narrator, proclaims as Tokyo Olympiad draws to a close. It’s an election year, and so his sentiment takes on a double meaning unforeseen by Ichikawa and likely unintended by Criterion. Those of us watching at home while sheltering in place will appreciate the thought, even if the dream feels more like a waking nightmare. But that’s all the more reason to absorb Tokyo Olympiad in the first place: This is a movie about the best of what mankind can be when joined under common cause, filmed with a level of craftsmanship unmatched since. —Andy Crump

The Cameraman Year: 1928

Year: 1928

Director: Buster Keaton

Stars: Buster Keaton, Marceline Day, Harold Goodwin, Sidney Bracy, Harry Gribbon

Genre: Comedy

Runtime: 69 minutes

On the subject of failure, here’s Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman. Criterion either knows how to find a theme or they’re accidentally gifted at pairing up unexpected movies through common experience: Like Ichikawa’s Tokyo Olympiad, The Cameraman has a soft spot for losers, except tintype photographer Buster (Keaton) is an actual loser rather than an Olympian loser. Nothing he does goes right. It’s not that he’s unlucky. It’s that he’s a hapless schlemiel. Then he catches a glimpse of Sally (Marceline Day), develops an instant crush, and endeavors tirelessly to get close to her, fucking up left and right all the while in his pursuit of love. Along the way, he makes friends with a monkey. This is about the most positive development in Buster’s life right up to the end of the movie. And Keaton makes us laugh all along the way. The combination of desire, ineptitude, and resultant calamity makes an unexpectedly sweet tonic with bitters provided by the story behind its production. For the background, read Imogen Sara Smith’s insightful essay; for guffaws, just watch its brisk 69 minutes. —Andy Crump

Portrait of a Lady on Fire Year: 2019

Year: 2019

Director: Céline Sciamma

Stars: Noémie Merlant, Adèle Haenel, Luàna Bajrami

Genre: Drama, Romance

Runtime: 119 minutes

French director Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire revels in the far-reaching history of women—their relationships, their predicaments, the unrelenting bond that comes with feeling uniquely understood—while also grappling with the patriarchal forces inherent in determining the social mores that ultimately restrict their agency. The film, which takes place sometime before the French Revolution in the late 18th century, introduces us to Marianne (Noémie Merlant), an artist commissioned to paint the portrait of an aristocratic young woman named Heloïse (Adèle Hannel), which, once completed, will be sent to Milan—where her suitor will covet it until his betrothed arrives. Completely resistant to the idea of marriage, Heloïse has sabotaged previous attempts, leaving Marianne with a difficult assignment. She must not reveal to Heloïse that she has been tasked with painting her, instead posing as a companion for afternoon walks, memorizing the details of Heloïse’s features and toiling on the portrait in secret. The class distinctions between Marianne and Heloïse point to an interesting exploration of the power dynamics at play within the muse/artist dichotomy, but even more beguiling about the relationship is that it is somewhat emblematic of Sciamma’s relationship with Hannel—the two publicly announced their relationship in 2014, amicably separating shortly before the filming of Portrait. Take another recent film that draws from a director’s real-life romantic relationship, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. Loosely based on Anderson’s marriage to Maya Rudolph, the film, although subverting many clichés of depicting artist/muse relationships, ultimately concludes with the power dynamic intact. Sciamma has no interest in following the oft-petty conflicts between creative types and their romantic partners, instead opting to present a bigger picture of a relationship forged out of the climactic act of knowing another person, not just feeling inspired by what they mean for one’s art. —Natalia Keogan

An Unmarried Woman Year: 1978

Year: 1978

Director: Paul Mazursky

Stars: Jill Clayburgh, Alan Bates, Michael Murphy, Cliff Gorman, Lisa Lucas, Pat Quinn, Kelly Bishop, Linda Miller

Genre: Drama, Comedy

Runtime: 130 minutes

Erica (Jill Clayburgh in an Oscar-nominated role) senses something off about her husband (Michael Murphy)—something that may just be stress having to do with his fancy Manhattan job, or anxiety around a doctor’s visit that happened to hit a little harder than usual now that he’s getting older—and it’s only a day or two later that he confesses he intends to leave her for a much younger woman. The reveal happens slowly enough—in Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman, the divorce isn’t exactly the inciting incident from which Erica’s exploration of late-’70s feminism wholly sprouts, more the natural result of too many years spent in the midst of unexamined monogamy, which Mazursky calmly sums up in the film’s opening by spending some time with Erica’s family, seemingly happy before the truth comes out. Though her ex pretty cleanly represents a typical white man going through a midlife crisis, the women in Erica’s life, and their many relationships with men, shine brighter in the light of Erica’s husband’s betrayal. As she starts going to therapy, dating and even sleeping around, Mazursky charts time through small, effortless conversations between Erica and friends, Erica and her teen daughter Patti (Lisa Lucas) or Erica and new lovers—developing a new romance with charmingly hirsute artist Saul (Alan Bates)—a broad survey of gender dynamics and modernity emerging from ordinary moments. With impressive ease and the obvious trust of his actors, Mazursky crafts a portrait of “an unmarried woman” as an ode to resilience, romance and the nameless passion that drives Erica to define herself as more than just an ex-wife. —Dom Sinacola