The 25 Best Albums of 1973

1973 was a big year for big music—Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon would become one of the best-selling album’s of all time, spending a whopping 741 weeks on the chart, and Led Zeppelin broke The Beatles’ record for the highest attendance at a concert with more than 55,000 at the Tampa Stadium. The Who released a double-album rock opera, and Stevie Wonder released one of two masterpieces. We asked the Paste music writers and editors to vote on their favorite albums from 50 years ago, and here are the 25 best albums of 1973.

25. Elton John, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road

25. Elton John, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road is perhaps the best example of the magic that was the Elton John-Bernie Taupin songwriting partnership. It produced some of John’s best-known tracks, including the rollicking “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting,” the Marilyn Monroe tribute “Candle in the Wind,” the titular ballad and the karaoke staple “Bennie and the Jets.” John seamlessly shifts from brash to mournful over the course of its 17 tracks, and the result is not unlike when Dorothy steps into the Technicolor land of Oz for the first time. —Bonnie Stiernberg

24. Lynyrd Skynyrd, (Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd)

24. Lynyrd Skynyrd, (Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd)

(Pronounced ‘l?h-’nérd ‘skin-’nérd) introduced the world to both the quintessential Southern rock band at the height of its powers and the epic “Free Bird,” empowering decades of slow-witted would-be hecklers with the ability to provoke audible groans from any audience throughout the world. More importantly the album features two of the absolute greatest rock songs of all time, “Simple Man” and the elegiac “Tuesday’s Gone. ”—Garrett Martin

23. Bob Marley & The Wailers: Burnin’

23. Bob Marley & The Wailers: Burnin’

For listeners who may only know Bob Marley’s musis through the ubiquitous Legend compilation, a true misconception would be that his music is colored by a sunny, positive, outlook on the world. The truth is, Marley, much like Curtis Mayfield or Fela Kuti, wrote as much about his anger towards the injustices being committed against his people in Jamaica and the oppressed around the globe as he did about the redemptive powers of love. On their sixth album Burnin’—the last true album as The Wailers since founding members Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer would leave the group shortly after its release—Marley and the group offer their fiercest calls to action up until that point. The most recognizable tunes here are the immortal anti-authority anthems “Get Up Stand Up” and “I Shot The Sheriff.” But perhaps the album’s hidden thesis statement is it’s closing track, the seething “Burnin’ and Lootin’.” The song takes the positive outlook of his peer Jimmy Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross” and calls out how futile the kumbaya approach towards militarized police aggression truly is. “How many rivers do we have to cross before we can talk to the boss,” he asks with an inflection so palpably frustrated you can envision his tightly clenched fist in the vocal booth. Evil and oppressive forces only listen to strong action. Marley knows this and that’s why his call for not only “burnin’ and lootin’” but burning “all illusion” of a society that works for all remains as powerful as ever today. —Pat King

22. Judee Sill: Heart Food

22. Judee Sill: Heart Food

Swooning neo-classicism, godly choral arrangements, and hints of Christian theology converge on Judee Sill’s second and, sadly, final studio album. Awash in strings and a deep yearning for redemption, Heart Food is as peculiar as anything that emerged from the early seventies folk scene. It’s also a work of astonishing melodic brilliance, with tunes like the lush, aching “The Kiss” and the eight-minute tapestry of “The Donor” ranking among the singer’s defining works. After the album failed to sell, a frustrated Sill blamed label head David Geffen and eventually sank into drug addiction, leading to an early death in 1979. Once obscure, her songs have found a second life in recent years, thanks to some posthumous reissues and a cult of contemporary artists, among them Joanna Newsom, Robin Pecknold, and Andy Partridge, fervently praising her genius. —Zach Schonfeld

21. Herbie Hancock: Head Hunters

21. Herbie Hancock: Head Hunters

The early ’70s found keyboardist Herbie Hancock, as he put it, “spending so much time exploring the upper atmosphere of music and the more ethereal kind of far-out spacey stuff” with his group Mwandishi. To move forward, he needed to ground himself. To do so, he constructed a new band featuring saxophonist Bennie Maupin and bassist Paul Jackson, and with them, started working in a space where funk and jazz danced together lasciviously. The four tracks they conceived for Hancock’s masterpiece Head Hunters are earthy and nasty. In their collective hands, “Watermelon Man,” a song from Hancock’s bop days became a slow strut across a nightclub dancefloor, and an ode to Sly Stone zips along like a copy of There’s A Riot Goin’ On playing at 78 RPM. And what seems like a soft landing in “Vein Melter” is actually a seamy little composition akin to sinking uncomfortably into a bed of wet potting soil. —Robert Ham

20. John Cale: Paris 1919

20. John Cale: Paris 1919

Following his firing from the Velvet Underground, John Cale took some time to find his musical footing. His first efforts were a furtive, unsteady mix of rock and classical, or excursions into motorik minimalism with his friend Terry Riley. Paris 1919 was where Cale found his center. Working with a backing band that included members of Little Feat and Wilton Felder of the Crusaders, the Welsh singer-songwriter developed a stronger musical voice that allowed him to get deep into the weeds of blues boogie rock, pure folk, baroque pop and moments of grandiosity. Cale’s balancing all of these disparate elements and finding the right blend of the poetic and ribald in his lyrics set the template for the rest of his illustrious career — a hot streak that, even with the release of this year’s Mercy, remains unbroken. —Robert Ham

19. John Prine: Sweet Revenge

19. John Prine: Sweet Revenge

On John Prine’s third album Sweet Revenge, the singing-mailman and poet laureate of working class Illinois took a bit of a pivot from the well-defined and empathetic voice he presented so fully formed on his first two albums. On this new set of songs, he lifts his sheepish smile to reveal his fangs. It’s as if all of his studies of humanity on his self-titled and Diamonds In The Rough made him understand another possible side of the coin: maybe people ain’t no good? The blasted out chords on the opening title track present him in the most brash he had come across in his whole career. “I got kicked off of Noah’s Ark / I turn my cheek to unkind remarks / There was two of everything / But one of me,” he snarls with a defiant middle-finger. The album also contains “Christmas In Prison,” which Prine had always had to justify as more of a sly metaphor on the shackles certain relationships can create rather than the bonding between inmates during the holiday season. That was the man’s super power, it could take a car ride before knowing when if he was consoling you or sharpening a dagger with his words. On the downright paranoid “Mexican Home,” Prine writes home to his mother from his painfully hot new locale down below the border. He drinks with a friend fearing the sun going down and searching for missing “sacred core” that burns inside of him. Later on “A Good Time,” he begins to reckon with actions that may have pushed him to the outside of where he would like to be. “And you know that I could have me a million more friends / And all I’d have to lose is my point of view,” he sings, “But I had no idea what a good time would cost / Till last night when I sat and talked with you.” If you can trust yourself, who can you trust? —Pat King

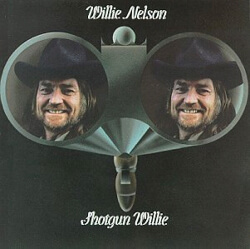

18. Willie Nelson: Shotgun Willie

18. Willie Nelson: Shotgun Willie

Reading the phrase “Outlaw Country” can induce an eye roll hard enough to get an up close view of your own wrinkly grey matter. Though, it’s worth noting that in the early 70’s, the industry did not take kindly to country artists with as visionary a scope as Willie Nelson. There was a real law of the land to be at odds with. The legendary songwriter made RCA a lot of money writing hits for artists like Patsy Cline at the start of his career, but in the 15 albums he made with his name front and center, the stringent label would not allow him to indulge in his love of musical stylings like jazz, rock or R&B nor was he allowed to use his own touring band on recordings. In 1972, he cut ties with his gatekeepers at RCA, moved to Austin, and signed a deal with Atlantic records that would allow Nelson to lean in hard on his freaky side. His 1973 album Shotgun Willie can be viewed as an A.D. period in his long discography. A true coming out for the songwriter and a seminal album for countless free-thinking country artists that sprung from it’s wake. Songs like the one-two-punch of the title track and the classic “Whiskey River” bring a joyous funky bottom immediately showcasing how unchained Nelson’s songwriting had become. But that doesn’t mean he lost his penchant for tearjerkers, as “Sad Songs and Waltzes” ranks amongst his very best. Perhaps the standout of the entire album is it’s closer—and one that Nelson did not write at all—a cover of Leon Russell’s immortal “A Song For You.” Nelson eschews the original versions string laden arrangement, instead brining it to it’s raw-essentials. Alone with just his tender voice and his legendary beat-to-shit classical guitar “Trigger,” he wrings out every bit of longing in the song to capture it’s solitude-in-the-spotlight essence. —Pat King

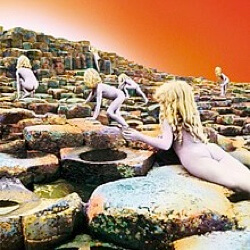

17. Led Zeppelin: Houses of the Holy

17. Led Zeppelin: Houses of the Holy

Houses marked a real departure for the band after four numeric juggernauts—Rolling Stone initially hated it, before ultimately bestowing a five-star rating 30 years later. Houses is off-beat for the band, but that’s its charm. The transition to the more eclectic style would find its apex on Physical Graffiti. Like Robert Christgau wrote at the time, “I could do without “No Quarter.’” But that track is listenable in the context of the entire album. “Dancing Days” really is danceable. “D’Yer Mak’er” (pronounced “didja maker”) is the unforgettable Zeppelin take on reggae, with the tropical solo from Plant. “The Rain Song” soars. “The Song Remains the Same” is kinetic but the sped-up Plant vocal is love-it or hate-it. And “Over the Hills and Far Away” is arguably the greatest Zeppelin song ever. From front to back, Bonham sounds like he’s going to pound his way right through the speakers and into your brain. —Michael Salfino

16. Can: Future Days

16. Can: Future Days

After the fraught yet successful sessions that yielded their previous album Ege Bamyasi, the members of Can allowed themselves to stretch out and relax a little bit — as much as their workaholic tendencies and furtive creative minds would allow anyway. The Krautrock group’s fourth studio album is shot through with a good amount of open air, with jams lingering a lot longer as the musicians tease out various grooves and shades of atmosphere. Even the poppiest number of the record, “Moonshake,” has a hushed quality perfect for long late night drives or shadowy prowls through your city of choice. For all the space in these songs, singer Damo Suzuki couldn’t seem to find his way in. His contributions are sporadic, leading, in part, to his departure from the group following sessions for this album. When he does pop up, particularly on “Spray” and in spots on the nearly 20-minute closer “Bel Air,” Suzuki adds the perfect jolt to the Can groupthink. —Robert Ham

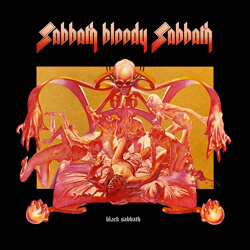

15. Black Sabbath: Sabbath Bloody Sabbath

15. Black Sabbath: Sabbath Bloody Sabbath

Like most bands of the era, Black Sabbath kept up an unrelenting pace in the early ’70s. Albums came out at a steady clip and in between studio sessions, they toured constantly. Keeping them aloft through it all was a stream of intoxicants and stimulants. By the time they hit L.A. in 1973 to begin writing album number five, they were spent and nothing came out. Instead, the quartet decamped to a castle in England where the lush surroundings and haunted atmosphere brought them back to creative life. What poured out of them was Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, an album that perfected Sabbath’s combination of turgid riffs and fluid grooves. It’s a familiar mix that marked much of the NWOBHM, but Sabbath took it to a much darker and weirder place than most with songs sung from the perspective of an unborn child (“A National Acrobat”), or tracing the growing dystopian landscape of their native England (“Who Are You?”) or simply tracking their collective mental and spiritual decline (“Killing Yourself To Live”). —Robert Ham

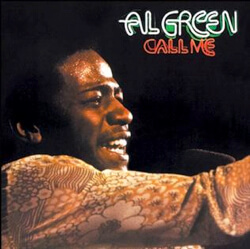

14. Al Green: Call Me

14. Al Green: Call Me

The tension between Al Green’s soulful eroticism and his devotional piety was obvious throughout his career. This title, one of his greatest albums, contains two irresistible, seductive come-ons, “You Ought To Be With Me” and “Call Me (Come and Take Me).” Both were top-10 pop hits and both were possible only because Green learned every growl, squeal, whisper and shout in the pews of his childhood church. But the album ends with “Jesus is Waiting,” on which he plays acoustic guitar and pours out his torment: “Help me, help me … save my soul.” Bridging the two sides of the canyon is his secret ingredient: country music, heard here in the form of songs by Hank Williams and Willie Nelson. —Geoffrey Himes

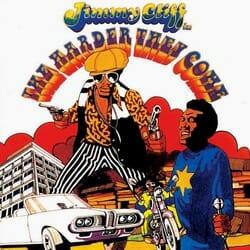

13. Various Artists, The Harder They Come soundtrack

13. Various Artists, The Harder They Come soundtrack

There was a lot more to the early years of reggae than Bob Marley & the Wailers, and the best of the rest is brilliantly summarized on this soundtrack album for one of the best fictional music films ever made. Once they realized they weren’t going to get any Wailers tracks, the filmmakers chose brilliantly. As the charismatic outlaw/singer/star of the movie, Jimmy Cliff sang half the songs, but there’s not a bad cut in the original soundtrack’s dozen. Included are reggae’s best-ever ballad (Cliff’s “Many Rivers To Cross”), best-ever pop hook (the Maytals’ “Sweet and Dandy”) and such one-hit wonders as the Slickers and Scotty. The 2003 “Deluxe Edition” reissue adds a second CD with 18 more songs, as smartly chosen as the first disc. —Geoffrey Himes

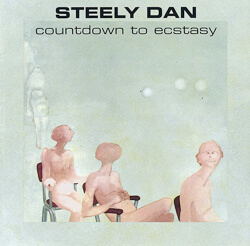

12. Steely Dan: Countdown to Ecstasy

12. Steely Dan: Countdown to Ecstasy

Just one year after releasing their debut LP, Can’t Buy a Thrill, Steely Dan—Walter Becker, Donald Fagen, Jim Hodder, Denny Dias and Skunk Baxter—reassembled at the Village Recorder in West Los Angeles to make Countdown to Ecstasy amid the departure of vocalist David Palmer. Like Thrill, it employs a big jazz and blues influence, and Fagen’s lyrics gleaned social and class critiques behind a band name they hawked from a type of dildo in a William S. Burroughs novel. On Countdown to Ecstasy, there are flickers of the Hollywood underbelly that plagues Gaucho—most-obviously in “King of The World,” when Fagen sings: “If you come around / No more pain and no regrets / Watch the sun go brown / Smoking cobalt cigarettes / There’s no need to hide / Taking things the easy way / If I stay inside / I might live ‘til Saturday”—but it would be a few more years until Steely Dan wrote their masterpiece Aja. Yet, Countdown to Ecstasy is the perfect, theatrical first chapter, as the band set their sights on chronicling the polarizing and unloved mythicality of their sleazy, city-stained streets. —Matt Mitchell

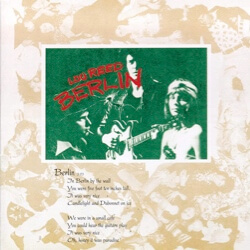

11. Lou Reed: Berlin

11. Lou Reed: Berlin

When Bob Ezrin entered into discussions about producing Lou Reed’s third solo album, he issued the former Velvet Underground leader something of a challenge. The stories in Reed’s songs were great but Ezrin felt that had no resolution. What, for example, became of the addict couple at the center of “Berlin,” a song from Reed’s self-titled LP? The songwriter responded by writing an entire album about Caroline and Jim, junkies living in Germany dealing with the occasional highs and crushing lows of their life. The album that Reed and Ezrin built around these songs is darkly beautiful with gorgeous acoustic guitar-led arrangements and delicate playing that run up against the ugliness within each song. The stately swing of “The Kids” opens up to reveal the nightmare of Caroline having her children removed from her care. The floating, angelic melody of “The Bed” helping soften the blow of the suicide at the song’s core. Coming on the heels of the glam-pop Transformer, critics couldn’t handle the bleak tone of Berlin, with many dismissing it completely. Time has repaired that massive oversight with most agreeing that this is one of many high points in Reed’s storied, varied discography. —Robert Ham

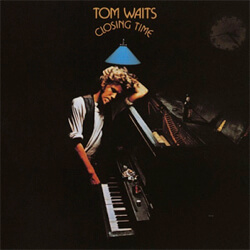

10. Tom Waits: Closing Time

10. Tom Waits: Closing Time

Tom Waits’ debut LP, Closing Time, is a brilliant project to revisit. After trying to make it as a troubadour folk singer in San Diego, Waits migrated north to Los Angeles and took stock as a songwriter living in the impoverished, bohemian neighborhood of Silver Lake. When he met David Geffen and inked a deal with Asylum Records, he made Closing Time at Sunset Sound. What an introduction it was for Waits, whose distinctive vocals had not yet taken the gravelly shape we’ve all come to know and love. Unfortunately, in 1973, next-to-nobody bought Closing Time. Thankfully everyone else caught on to Waits’ brilliance pretty soon after. He had wanted to make it a jazz singer, piano-forward type of album, though, through label pressure, it came out like a country-folk lullaby. Songs like “Ol’ 55” and “I Hope That I Don’t Fall In Love With You” and “Old Shoes (& Picture Postcards)” are songs I still return to constantly, even when the tracklists of Rain Dogs and Blue Valentine are always right there. Waits would start transitioning to the crooning, Beat Generation-inspired blues and jazz sound he idolized at full-speed a year later on The Heart of Saturday Night, but Closing Time is a grand document of a new face in Hollywood just trying to catch a train to success. It’s also one of the finest debuts of the last 50 years. —Matt Mitchell

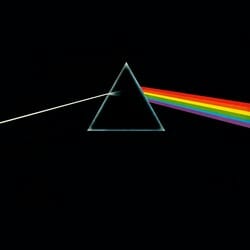

9. Pink Floyd, The Dark Side of the Moon

9. Pink Floyd, The Dark Side of the Moon

More than just a cultural institution, Pink Floyd’s eighth album is a landmark achievement in what rock music in the 1970s could become. For the band, it represented a global smash unlike any previous release, translating their penchant for often abstract prog into a more accessible format. As a “concept album,” The Dark Side of the Moon expanded the term’s boundaries to its most literal definition, cohesively threading broad explorations of madness and existentialism. But, above all, it endures as a formidable powerhouse of a record, in sound and conceptual execution—staggering, moving, just as pristine as ever. Its defining moments rest in its ability to capture inarticulate emotion as on Clare Torry’s vocal performance on “The Great Gig in the Sky,” or the bursts of release that make “Us and Them” and “Brain Damage/Eclipse” especially dynamic compositions. In its poignance, The Dark Side of the Moon remains Pink Floyd at their most transcendent, a release as brilliant in construction as it is immensely cathartic. —Natalie Marlin

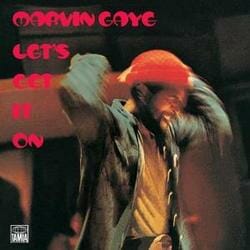

8. Marvin Gaye: Let’s Get It On

8. Marvin Gaye: Let’s Get It On

Imagine making an album so charged with erotic energy that its first four, wah-wah-coated notes alone are enough to put you in the mood or set the tone for a sex-scene needle drop. After chronicling social unrest on 1971’s pivotal What’s Going On, Gaye shifted from the podium to the bedroom on Let’s Get It On, marinating in a sensual, funk-infused sound that set the template for the modern slow jam. While the title track is a staple of sex playlists from here to Saturn, much of the album finds Gaye tormented by unfulfilled longing, as on the desperately swooning “Distant Lover” or the flickering elegy of “Just to Keep You Satisfied.” This is soul so smooth it melts to the touch. —Zach Schonfeld

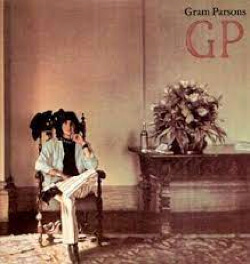

7. Gram Parsons: GP

7. Gram Parsons: GP

It’s often remarked how Parsons changed Emmylou Harris’ life, but she changed his life almost as profoundly. The purity of her soprano forced him to forego hippie sloppiness and focus on country singing in the classic mode. On GP, he responds with some of the best singing of his career, allowing Harris’ sweet harmonies to suggest the ideals he aimed for and using his own bruised tenor to suggest how short he fell of those goals. —Geoffrey Himes

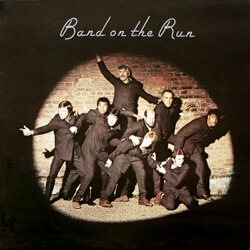

6. Paul McCartney and Wings: Band on the Run

6. Paul McCartney and Wings: Band on the Run

Just three years after the official dissolution of the Beatles, Paul McCartney had put out four great albums (McCartney, Ram, Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway), but none flaunted—at least at the time—the starpower or reverence that the bassist had captured after a decade spent crafting all-time show-stoppers like “Hey Jude,” “Yesterday” and the Abbey Road Medley. All of that changed when he, his wife Linda and their longtime collaborator Denny Laine assembled in August 1973 to make the third Wings album. The product was Band on the Run, one of most-perfect pop rock records of the 1970s. Few side ones are impenetrable, and “Nineteen Hundred and Eighty Five” is in the echelons of McCartney’s funkiest creations. To see him play “Band on the Run,” “Jet” and “Let Me Roll It” live only solidifies the tracklist’s enduring legacy, as Band on the Run goes toe-to-toe with some of the Beatles’ best. And, 50 years later, it remains a pristine document of McCartney’s status as one of our greatest songwriters. The project revitalized his career and turned Wings into one of the biggest bands in the world. And to know that “Helen Wheels” was recorded during the Band on the Run sessions but left off of the final cut, one can’t help but admit that McCartney had, again, reached the top of the mountain. —Matt Mitchell

5. Bruce Springsteen: The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

5. Bruce Springsteen: The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

I recently saw Springsteen play a gargantuan, three-hour set on his highly anticipated world tour. Lucky for me, he crammed almost half of The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle into a setlist that catered to fans of every era far and wide. I have always been deeply in love with Springsteen’s second album, because it’s the one where his trademark sound is at its most-beautiful. Earlier in 1973, he put out Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and began his ascent to becoming a blue-collar Mozart, but the stories Springsteen sang about here—the romanticized odes to working class nights tumbling into metropolitan dreams of success—are still vivid. And, with his beloved E Street Band in tow, The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle is a masterclass of rag-tag rock ‘n’ roll stuffed to the brim with jazz and blues. Beloved tenor saxophonist Clarence Clemons was a larger-than-life voice across the album’s arrangements, cascading on a wave of gorgeous brass from “The E Street Shuffle” all the way to “New York City Serenade.” Four of the seven songs are over seven minutes long, an appropriate representation of Springsteen’s tendencies to stretch radio-friendly runtimes into suites and concertos on-stage. Up until 1985, “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)” was Springsteen’s most-used show closer, and nothing makes more sense. Take The Wild, The Innocent & the E Street Shuffle and you’ll have a perfect snapshot of the tightest band in the world firing on all cylinders. I’ll ride into the teeth of a New Jersey night with Sloppy Sue, Weak Knees Willie, Jack the Rabbit and Big Bones Billy anyday. —Matt Mitchell

4. David Bowie: Aladdin Sane

4. David Bowie: Aladdin Sane

If 1972’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars marked the moment David Bowie had finally arrived as alien messiah to deliver glam rock’s good news, its follow-up was inevitably going to bear the rough edges which come with the ways sudden fame and rigorous touring wear an artist down. As expected, then, Aladdin Sane acts as a sleazier, looser travelog of all the places Bowie’s newfound stardom had taken him up to that point, leading him to refer to it as his document of “Ziggy under the influence of America.” Taking clear inspiration from both The Rolling Stones and American glam contemporaries The New York Dolls, tracks like “The Jean Genie,” “Watch That Man” and “Cracked Actor” are part-hedonistic character sketch, part-glitter-drenched blues-rock workout. Elsewhere in the tracklist, session pianist Mike Garson’s jazz background helped to expand Bowie’s sonic palette, creating space for the erratic drama of the album’s title track and “Time,” as well as the majestic balladry of closer “Lady Grinning Soul.” With its deep-dives into such disparate musical moods interwoven with tales of washed-up screen stars and seedy underbellies of American cities, the project became impossible to sustain: three months after Aladdin Sane’s release, Bowie would famously kill off his Ziggy Stardust persona on stage. Though often regarded as a weaker retread of the path its predecessor paved, the album serves as a portrait of an artist struck by lightning–not long for the world his alter ego occupies, but burning gorgeously bright while the record is still spinning. —Elise Soutar

3. The Who: Quadrophenia

3. The Who: Quadrophenia

Four years after releasing their first rock opera, Tommy, Pete Townshend conceived, wrote and creatively oversaw an even more ambitious project telling the struggles of Jimmy, a disillusioned working-class mod over the course of two LPs. It’s an empathetic look at youth culture in Britain told over 17 tracks and accompanied by photo illustrations and text version of the story. “I’m getting put down / I’m getting pushed round / I’m being beaten every day,” Roger Daltrey sings in “The Dirty Jobs.” But a rock opera is only as good as its songs, and with hits like “The Real Me” and “Love, Reign o’er Me” and complex instrumentals like the title track make this one of the band’s best releases. —Josh Jackson

2. Iggy and The Stooges: Raw Power

2. Iggy and The Stooges: Raw Power

The recording of Raw Power was a mess; touring for the album was even messier. By the time 1973 came around, the Stooges—or Iggy and The Stooges, or the Psychedelic Stooges—were pioneers, the definition of proto-punk. Peers like MC5 and the Sonics were excellent at making garage rock raucous like the Stooges had. In retrospect, they were the blueprint of punk rock. And, under the leadership of Iggy Pop, the Stooges brought theatricality to rock ‘n’ roll that wasn’t avant-garde or esoteric. Like a cauldron of blood, sex and anger, Raw Power is the antithesis of delicate. A monolith of brash. For their five years together, the Stooges were grossly unloved by the masses. Critics loved Raw Power, though. Creem journalist Lester Bangs, who infamously first referred to the band as “punk rock,” praised the album for “the ferocious assertiveness of the lyrics” that were “at once slightly absurd and indicative of a confused, violently defensive stance that’s been a rock tradition from the beginning.” Bangs was right, but he was also horribly wrong. What Pop and the Stooges did on Raw Power was singular and remains as such in 2023. —Matt Mitchell

1. Stevie Wonder: Innervisions

1. Stevie Wonder: Innervisions

Though he was only 23 when he wrote and recorded Innervisions in 1973, Tamla/Motown guru Stevie Wonder already had 15 albums under his belt and was one of the biggest singer/songwriters on the planet. After releasing two number-one hits in 1972—“Superstition” and “You Are the Sunshine of My Life”—no other act in the world could catch his flame. The third entry in an unparalleled run of five albums (sandwiched in the middle of Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Songs in the Key of Life and Hotter than July), Innervisions remains one of Wonder’s greatest feats, a project that solidified him as a titan of funk and soul. There’s a reason it won Album of the Year at the 1974 Grammy Awards: Songs like “Higher Ground,” “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing” and “Living for the City” are perfect, unparalleled compositions tackling everything from love to drug addiction to racial inequality. The record took great aim at the Nixon administration, and Wonder even implemented traffic noise and cop sirens into the studio arrangements to bring the depictions of systematic racism into an even more vivid space. Few musicians have ever had an apex like Wonder’s, and Innervisions is one of the greatest albums ever made. —Matt Mitchell