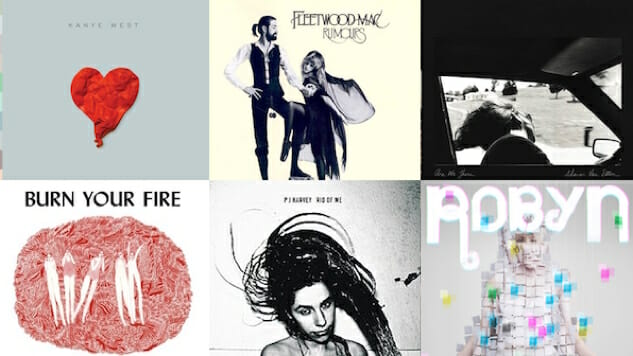

The 30 Best Breakup Albums of All Time

While Valentine’s Day and its host month February are presumably about love and feeling it/showing it/making it whenever and wherever you can, this gray, dreary month can feel a little lonely if you’ve recently weathered a breakup. Thankfully, February 2019 also brought us a slew of great new breakup albums (Martin Frawley’s Undone at 31, Julia Jacklin’s Crushing and, yes, even Ariana Grande’s thank u, next), just in time to help those of us feeling a little broken block out the swarm of pink and red, flowers and candy.

Those albums got us thinking about our other favorite breakup albums, those records we turn to when music is the only thing that numbs the pain. These are the albums in your record collection that might prompt a chorus of “Who hurt you?”s from friends and family. And, to be fair, “Are you okay?” seems like an appropriate question if you’re exclusively listening to The National after a breakup. But these albums aren’t for when you’re okay. They aren’t the get-up-and-go records for cheering you up when you’re sad. These are the albums in which you can wallow. So crawl under a blanket, fetch a bucket of ice cream and crank up Lorde’s Melodrama until you can’t hear your own thoughts. This is a safe place to sob.

Here are the 30 best breakup albums of all time, as voted by the Paste Staff:

30. Robyn, Body Talk

30. Robyn, Body Talk

We can’t talk about heartbreak in music without mentioning Robyn. Whether you need to sob into your pillow or sweat yourself into oblivion at the club, the Swedish pop diva is always there with the right remedy for your pain. Her latest album, Honey, is a stunning dancefloor masterpiece with a few heartbreak tunes mixed in with the electro bliss, but 2010’s Body Talk is home to arguably one of the greatest breakup songs of all time, “Dancing On My Own.” After an expertly placed appearance in a scene from the third episode of GIRLS, even more people recognized “Dancing On My Own” for what it really is: a juicy, devastating wave of catharsis. And upsetting as it is, Robyn’s recount of watching her ex-lover run away with someone else isn’t exclusive to the broken-hearted among us. Like Lena Dunham’s Hannah, sometimes you just need it as a boost, to remind yourself that you’re okay—maybe even better—on your own. —Ellen Johnson

29. Bruce Springsteen, Tunnel of Love

29. Bruce Springsteen, Tunnel of Love

Following a series of uplifting anthems and albums that touted his role as an American Everyman, Bruce Springsteen reached his moment of true reckoning with the decidedly downturned Tunnel of Love. The reasons were clear. His marriage to actress Julianne Phillips was falling apart, and his relationship to his erstwhile backing ensemble, the E Street Band, was frayed due to separation. Consequently, Springsteen chose to record the album on his own, overdubbing the instruments and limiting the group members’ participation to only a few cameos. The songs themselves were telling reflections of Springsteen’s somber perspective and loss of faith in any ability to sustain a real relationship. One song in particular, “Brilliant Disguise,” summed up the sentiment: “So tell me what I see when I look in your eyes / Is that you baby or just a brilliant disguise…” That’s but one of many offerings that express doubt and despair, and it captures the anguish felt by anyone who finds it difficult to discern the connections that can be counted on versus those that are transient and untrue. To quote again from the same song, “God have mercy on the man / Who doubts what he’s sure of.” Indeed! —Lee Zimmerman

28. Frank Sinatra, Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely

28. Frank Sinatra, Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely

After a tumultuous divorce from Ava Gardner in 1957, Frank Sinatra released Frank Sinatra Sings Only for the Lonely the following year. Already prone to depression (Sinatra made three suicide attempts during his relationship with Gardner, famously calling himself “an 18-Karat manic depressive”) Sinatra repeated his recipe for sullen success that he had perfected on 1955’s In the Wee Small Hours on Only the Lonely—the albums even share the same visual motif of Sinatra lit by a lone lamppost. Only the Lonely features a range of saloon songs, and if it weren’t for Nelson Riddle’s decadent string arrangements, the album would sound like a private performance for Sinatra’s bartender. (The album literally features “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road),” which is directly addressed to a bartender.) “Come Fly With Me is one Sinatra. All the Way is another Sinatra. A Sinatra singing a hymn of loneliness could very well be the real Sinatra,” reads the back cover of the album—with songs this sad, maybe it’s true. —Katie Cameron

27. Lorde, Melodrama

27. Lorde, Melodrama

On Melodrama, Lorde’s glittering electropop triumph, the New Zealand singer-songwriter finds herself immersed in exhilarating, champagne-soaked parties and soul-crushing one-night stands, and witnessing the inevitable disintegration of her youth. Her continued fascinations with the highlife, royalty and growing old that formed the core of her debut album—2013’s Pure Heroine—are still present but she now possesses a deeper layer of self-identification and a startling vulnerability. The percussive buildup and splashdown on the post-disco opener, “Green Light,” sets a happy/bitter tone: her breakup has left a scar that she’s happy to show off. The rapidly reverberating percussion of “Homemade Dynamite” brings an absolutely liberating chorus, but the glut of lyrics on the tamer “The Louvre” doesn’t quite let the song’s “broadcast the boom” anthem stand out. She continues to detail her failed relationship on the tender piano ballad “Liability” while acknowledging her shelf life as a musician is extremely perishable, and the buoyant “Supercut,” with its fusion of ’80s pop with an electro-house beat, echoes Pure Heroine’s brazen drive. Her early wisdom signifies an old soul. Where Pure Heroine was her global, future-forward debut, Melodrama is the red-eyed, no-rules afterparty, where the lost and loveless go for comfort. —Emily Reily

26. Frightened Rabbit, The Midnight Organ Fight

26. Frightened Rabbit, The Midnight Organ Fight

Never before has a breakup album felt this honest, vulnerable, and just plain raw. The Midnight Organ Fight, a no-holds-barred account of the dissolution of the late, great Scott Hutchison’s on-again-off-again relationship that would seemingly never end, is as bleak as it is beautiful, equally dark and life-affirming. Beginning with a longing for things to be normal again (“You should sit with me and we’ll start again / And you can tell me all about what you did today” from “The Modern Leper”), Hutchison’s account shines a light on every distressed moment following the initial dreaded conversation to end a long-term relationship—from jealousy (“I don’t want you back / I just want to kill him” from “Good Arms vs Bad Arms”) to longing for meaningless sex (“You twist and whisper the wrong name / I don’t care and nor do my ears / Twist yourself around me / I need company I need human heat” from “The Twist”) to revisiting his ex for yet another failed attempt at reconciliation (“I’ve been working on my backwards walk / There’s nowhere else for me to go / Just back to you just one last time / Say yes before I change my mind” from “My Backwards Walk”) to devastating acceptance (“And now we’re unrelated and rid of all the shit we hated / But I hate when I feel like this / And I never hated you” from “Poke”). Rarely, if ever, has a songwriter allowed him/herself to be as open, exposed, blunt, and poetic concerning the slow, painful march towards a final breakup following months—or years—of being unable to finally cut the chord and the brutal period that follows. We will likely never again see a record quite like The Midnight Organ Fight, a true masterpiece that becomes more revered over time as additional people find a helping hand in Hutchison’s words as they suffer through similar circumstances. —Steven Edelstone

25. Carly Rae Jepsen, Emotion

25. Carly Rae Jepsen, Emotion

At first glance, a record with songs like “I Really Like You” and “Run Away With Me” may not seem like obvious choice for a stellar breakup album. To that, we say, you clearly haven’t cried while listening to E•MO•TION by Carly Rae Jepsen. Post-breakup, you don’t just wallow in sadness or stew in bitter anger. You mourn what might-have-been and even dream about your ex running through the proverbial airport to tell you they made a huge mistake. Everything about E•MO•TION, including its fantastical retro-inspired pop sound, screams rose-colored glasses. Besides obvious breakup songs like “Emotion” and “Your Type,” the album is filled with tracks that, if anything, feel like desperate, unattainable fairytales. And let’s not forget the album’s most underrated song, “Boy Problems,” which feels like a glittery chorus of every pal ever who’s reminded you that friendship comes before an obnoxious S.O. If a Disney princess made a record after being dumped, this masterpiece would be it. —Clare Martin

24. Sharon Van Etten, Are We There

24. Sharon Van Etten, Are We There

Though most of Are We There steers through the tumult of a relationship that has since ended (the song titles tell the story: “Your Love Is Killing Me,” “I Love You But I’m Lost,” “Nothing Will Change,” “Break Me”), Van Etten never wallows, nor turns vengeful or bitter. Rather, these songs are her attempt to make sense of it all, and she sifts through the promise, the heartache and the loneliness with dignity, even elegance. That’s not to suggest she hides her anguish. Van Etten lets loose on “Your Love Is Killing Me,” her voice throbbing as she fights, essentially, for the space to catch her breath. She is sorrowful over eddies of guitar and thundercloud drums on “You Know Me Well,” while a sympathetic horn vamp acts as a keel to keep “Tarifa” right-side up against Van Etten’s forceful swings between wild hope and despair. —Eric R. Danton

23. Radiohead, A Moon Shaped Pool

23. Radiohead, A Moon Shaped Pool

Most Thom Yorke lyrics hang suspended in a dream-like state, blending imagistic poetry with vague emotional outcries—an ambiguity that keeps the songs relatable, even if we don’t know what’s fueling the melancholy. A Moon Shaped Pool finds the frontman brooding even more than usual: He observes “gallows,” a hovering “dread,” a “spacecraft blocking out the sky.” On moon-lit reverie “Glass Eyes,” he exits a train at a “frightening place” and encounters faces of “concrete grey”—but instead of turning back, he trudges forward down a mountain. “I don’t know where it leads,” he croons over crystalline strings and piano. “I don’t really care.” Yorke’s never approached strict confessional songwriting, but it’s hard not to read between the lines: In 2015, he separated from his longtime partner, Rachel Owen, and the ghosts of lost love linger in some of his barest lyrics. “You really messed up everything,” he intones on kraut-rock thrill ride “Ful Stop”; “Broken hearts make it rain,” he squeals, enraptured, on “Identikit”; the symphonic surge of “Daydreaming” closes with Yorke reversed and pitch-shifted, like a fire-breathing dragon: “Half of my life,” he huffs, a possible reference to his past relationship. The crushing blow is unavoidable—though projecting in too much backstory is a fool’s errand. —Ryan Reed

22. Joan Baez, Diamonds & Rust

22. Joan Baez, Diamonds & Rust

After making her name as the forlorn godmother of ’60s folk, Joan Baez made an abrupt turn in her trajectory and opted for her first real attempt to lure a mainstream audience with the emotionally charged Diamonds & Rust. To be sure, it didn’t dispel her downcast demeanor, given that a solid portion of its songs focused on themes of love and loss, especially of the decidedly splintered variety. The title track was clearly directed at Bob Dylan, her onetime paramour and the man with whom she was bound both musically and romantically. Her take on Bob’s “Simple Twist of Fate,” culled from Dylan’s own rumored break-up album Blood on the Tracks (also on this list), reinforced the tender yet tenacious trappings. Add to that, the honeyed heartache of Jackson Browne’s bittersweet “Fountain of Sorrow,” John Prine’s sad but serene “Hello in There” and Stevie Wonder’s longing lament “Never Dreamed You’d Leave in Summer,” and it’s all too easy to see how the sense of separation had intruded on the ambiance overall. The result is one of Baez’s best albums by far, but also one that ranks among her most decidedly despondent. —Lee Zimmerman

21. Rilo Kiley, More Adventurous

21. Rilo Kiley, More Adventurous

Heartbreak is a universal experience with few comprehensive truths. In Rilo Kiley’s tumultuous search for happiness, for answers, for anything at all, they tackled those truths as they came. One of them materialized as 2004’s More Adventurous, which exposed the harsh reality that heartbreak thrives in indifference, but often exists as a result from caring too deeply—which is probably why the album also serves as the reminder that we’re all just fox food in the end. More Adventurous shows us that heartbreak can manifest from the loss of love, will or sympathy. That sometimes it generates vitriol, regret or uncertainty. That sometimes it comes without warning, and sometimes with too much. And that sometimes, it just is. —Montana Martin

20. PJ Harvey, Rid of Me

20. PJ Harvey, Rid of Me

Rid of Me is breakup album as exorcism. Across these 14 tracks, a 23-year-old Polly Jean Harvey howls, moans, flirts with murder, relives the Book of Genesis, and shrieks at the listener to lick her legs. At the center of it all is her extraordinary voice, an unrelenting banshee wail that’s the aural embodiment of the album’s prevailing preoccupation with love as a form of violence. Harvey’s masterpiece draws on Captain Beefheart, feminist rage, mid-century blues, and Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited”; its production and engineering by Steve Albini, who achieved an uncompromising dynamic range rarely heard in modern recordings, has become as shrouded in myth as the songs themselves. It seems difficult to imagine circumstances that could produce songwriting this extreme—Harvey herself has cited a sense of exhaustion, malnutrition, and something close to a nervous breakdown—but generations of scorned lovers are grateful for its existence. —Zach Schonfeld

19. Best Coast, Crazy for You

19. Best Coast, Crazy for You

Best Coast’s Bethany Cosentino digs the simple pleasures: California summers, her cat, Snacks, and love. She really digs love. That penchant for simplicity bounces all over Best Coast’s debut, Crazy For You. After a string of sunny but sludgy EPs, Crazy features 13 tracks in 30 minutes. It’s the tightest, brightest music Cosentino and sole bandmate Bobb Bruno have pumped out yet. These tunes approach love and longing like a teenage diary entry (“I wish he was my boyfriend / I’d love him to the very end” pines Cosentino in “Boyfriend”), matching ’60’s girl group melodies with fuzzed-out guitars. There’s little variety here, but like The Supremes, the straight-ahead formula works: Sing about love, and make each chorus stick. And they do. —Justin Jacobs

18. Bon Iver, For Emma, Forever Ago

18. Bon Iver, For Emma, Forever Ago

Not since a creek drank a cradle in 2002 had anyone so quietly overtaken the indie-music community as Justin Vernon did in 2008 with Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago, when Jagjaguwar gave the album a wide release after Vernon pressed 500 copies himself the year before. This lonesome post-break-up album—with its mythic origin story in a remote Wisconsin cabin—is drenched in the kind of melancholy that feels a lot like joy, and sounds just as vivd. Rather than wallowing in loss, Vernon’s otherworldly falsetto and warm acoustic guitar provide a hopeful contrast to impressionistic lyrics like “Saw death on a sunny snow.” Vernon’s real trick was imbuing such hushed music with so much feeling and such seemingly nonsensical lyrics with such specific meaning to individual listeners. It was less like the end of a relationship and more like the promise of a new beginning. —Josh Jackson

17. The National, Trouble Will Find Me

17. The National, Trouble Will Find Me

Trouble Will Find Me may be The National’s funniest album to date. Not that it has a whole lot of competition. The bookish Brooklynites don’t typically drop punchlines, although Matt Berninger has snuck a few sharp absurdities into his lyrics. On the band’s sixth album, however, he actually foregrounds the humor, which is a welcome change for the band so deep into its career. Berninger’s self-deprecating humor nicely complements the album’s pealed-back sound. If High Violet was an ambitious statement album that propelled the band to new heights of mid-life/middle-class existentialism, Trouble Will Find Me is looser, easier and rawer—as laidback as The National ever get. Dense with allusion and mythology, Trouble portrays The National as a band that has soaked up so many influences that they’re bleeding out into the words. And yet, you don’t need to know who sang “Blue Velvet” or get the Elliott Smith reference on “Fireproof” to appreciate the band’s stripped-down sonic assault or sympathize with the confused protagonists wandering through these songs. —Stephen M. Deusner

16. The Beach Boys, Pet Sounds

16. The Beach Boys, Pet Sounds

While there is admittedly nothing original left to say about Pet Sounds, anyone who says the 1966 album is overrated is, without exaggeration, lying to you and to themselves. In the early ’60s, The Beach Boys’ songs about summer and cars and girls marketed them as an idyllic portrait of the white (and whitewashed) picket fence version of the American Dream; in reality, Brian was an anxious young man with an abusive father. In Pet Sounds’s 36 minutes, Brian creates an album whose thematic arcs of growing up and disillusionment implode the happy-go-lucky narrative surrounding the band. The album opens with a tinkling 12-string guitar solo on “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” when—crash!—in comes Wrecking Crew drummer Hal Blaine with a drum smack to successfully eliminate whatever innocence you thought Pet Sounds could harbor a whopping seven seconds in. There’s no throwaway tracks on the album, even in its two instrumentals. Brian denies the inevitable end of a relationship on the too dreamy “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder)” and experiments with a ghostly sounding Theremin on “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times” (it’s use on Mad Men haunts me to this day). Pet Sounds is an album of upending expectations—“God Only Knows” is possibly the most moving love song ever written, and its opening line is “I may not always love you,” so come on—of the studios who wanted commercial hits, of the audiences who wrote The Beach Boys off as surf rock noise and of the critics who felt that rock music had to sound a certain way. Its coming-of-age themes are as universal as they are painfully personal, making Pet Sounds, without a doubt, “a complete statement.” —Katie Cameron

15. Angel Olsen, Burn Your Fire for No Witness

15. Angel Olsen, Burn Your Fire for No Witness

Angel Olsen’s beautiful, sad and, ultimately, useful sophomore album, Burn Your Fire for No Witness is an experience obsessed with heartbreak, and engaging the record with a heavy heart of your own is excruciating—near-torture. But this is how Angel Olsen deserves to be absorbed, with empathy—knowing her pain and resolve and bravery, and using it for your own strength. It’s an album that tells the world we are not alone. It’s like Olsen was reading the language of heartbeats and sighed breaths and watery eyes. Closing number “Windows” asks “Won’t you open a window sometime? What’s so wrong with the light? Wind in your hair, sun in your eyes.” She so wants to love and to be loved that it’s as plain and simple as an open window and the sun shining in, and it confuses and torments her that her object of desire doesn’t see the world the same way. It’s the tragedy of any love that doesn’t work, and Olsen seems so willing to give that your heart can’t help but break for her. Her dry, almost rusty voice is pain made audible, like this isn’t her first heartbreak, like she’s endured lifetime after lifetime of them. Olsen shares graciously in her music, and if you are willing, Burn a Fire for No Witness will change your world—or, rather, it will change how you see your world. —Philip Cosores

14. Slowdive, Souvlaki

14. Slowdive, Souvlaki

Souvlaki makes for the rare shoegaze album with a lyrical and emotional depth to match its formidable sonic depth. And its not-too-well-kept secret is that it’s a breakup album. Rachel Goswell and Neil Halstead, Slowdive’s dual vocalists, knew each other since school days. Internet legend has it that they were romantically intertwined but dissolved their personal relationship before Souvlaki. The members have only ever hinted at such a scenario, but it would more than explain the heavy pall of heartbreak that hangs over Souvlaki. “Forty days and I miss you / I’m so high that I lost my mind,” Halstead sings on the noisy and desperate “40 Days.” The closing “Dagger” is even more devastating: “You know I am your dagger / You know I am your wound / I thought I heard you whisper / It happens all the time.” Souvlaki, then, is the Rumours for the dream-pop set, a bracing chronicle of heartbreak that finds each contributors to that heartbreak playing equal roles. —Zach Schonfeld

13. Marvin Gaye, Here, My Dear

13. Marvin Gaye, Here, My Dear

Marvin Gaye’s 1978 double album Here, My Dear is, quite literally, a divorce album, meaning that, as part of an alimony agreement with his ex-wife, he agreed to give her half the royalties for the record. Allegedly, he intended to handicap the deal by releasing a terrible record but let his anger and frustration at the experience fuel his work instead. And what came out of that was a suite of songs that ranged from the nakedly confessional “You Can Leave, But It’s Going To Cost You” (“Her lawyers worked so hard / tryna take my riches”) to the emotionally shattered to the surprisingly hopeful (“Falling In Love Again”). Gaye vivisects his marriage for all to see. While it had the desired effect of flopping up on its release, the album has gained a deserved reputation as being one of the most ambitious and satisfying of his long career. —Robert Ham

12. Beck, Sea Change

12. Beck, Sea Change

For a man so used to wearing musical masks, Beck lays himself bare on Sea Change. It’s the most aching, honest album he’s ever made, a musical breakup memoir on par with Blood on the Tracks or Shoot Out the Lights. To say his heart is on his sleeve here doesn’t capture the emotional nakedness; his heart is speared on a record spindle, and he lets us listen. And why wouldn’t we? With a full stock of golden melodies, crafty string arrangements, and career-best vocal performances, Beck is maybe the best American songwriter of his generation. —Steve LaBate

11. Blur, 13

11. Blur, 13

The jury’s still out on which Blur LP is their finest, but they make a strong case on 13. Their 1999 sixth studio album was written in the aftermath of Damon Albarn’s breakup with Elastica lead singer Justine Frischmann. It opens with the Primal Scream-esque “Tender” with its gospel choir vocals and altruistic lyrics like “Love’s the greatest thing that we have,” before descending into a fuzzy rock fit on “Bugman.” 13 might sound like a mad scientist’s experiment gone wrong, but it’s the album’s manic energy and wild experimentation that gives it its charm. The chunky, high-pitched vocal morphs and harmonica passages on “B.L.U.R.E.M.I.” and the pulsing, idiosyncratic noise of “Battle” can be interpreted as emblems of the chaotic upending of relationships. Breakups are a chance to take time for yourself and try on a bunch of different hats—and with 13, Blur put on as many sonic hats as they could get their hands on. Songs like “Trailer Park,” “Caramel” and “Mellow Song” reference Albarn and Frischmann’s drug use, which was likely a large point of tension in their relationship. Though “Coffee and TV” was written and sung by guitarist Graham Coxon and doesn’t directly allude to Albarn’s breakup, it represents a similar struggle to return to normalcy, this time referring to Coxon’s relationship with alcohol, and it’s one of Blur’s greatest-ever tracks. —Lizzie Manno

10. Carole King, Tapestry

10. Carole King, Tapestry

With Tapestry, Carole King grapples with the grief, anger and—eventual—hope at the end of a relationship with devastating honesty. Following her divorce from husband and songwriting partner Gerry Goffin, King left New York for Laurel Canyon where she met Joni Mitchell and James Taylor (i.e., Two More Singer-Songwriters Here to Emotionally Wreck You) who encouraged her to perform on her own album. The pair sang backup on Tapestry, which features both originals and covers that King had co-written with Goffin during their marriage, like her ugly cry-inducing version of “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” From the album’s bare bones cover (featuring King and her cat Telemachus, added for the last photo of the shoot) to her aching lyrical talents (just try to keep a dry eye during “Way Over Yonder”), King’s vulnerability is startling—and wholly responsible for the album’s resonate lasting power. —Katie Cameron

9. Kanye West, 808s & Heartbreak

9. Kanye West, 808s & Heartbreak808s and Heartbreak is a masterpiece in simplicity and huge emotions, making every sound and shift impactful. It’s Kanye at his most vulnerable and destroyed, trying to find some solace after a relationship has ended. The pinnacle of this comes in “Love Lockdown,” 808s and Heartbreak’s biggest single that is iconic of the themes and style of the album. With “Love Lockdown,” it’s all about how these little shifts occur and come together. There’s the basic TR-808 drum machine heartbreak underneath, as Kanye’s distorted voice and basic piano piece go through the first verse before gigantic drums blast in, leading to a conclusion full of animalistic sounds and power. On “Street Lights,” you can almost hear the next wave of hip-hop artists getting inspired for their own work. The gorgeous repetition and hazy sounds are reminiscent of Frank Ocean, Kid Cudi, and Drake, especially considering the introspective tone of the album. —Ross Bonaime

8. Amy Winehouse, Back to Black

8. Amy Winehouse, Back to Black

If all you heard on the radio in 2006 and 2007 were singles “Rehab” and “You Know I’m No Good,” you’d think the rest of the album was full of fun, upbeat numbers about sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll. But in the greater context of Back to Black, the two singles were Amy Winehouse’s cry for help, a coping mechanism to deal with her very public on-again-off-again relationship with Blake Fielder-Civil. But eventually, the wild partying and refusal to come to terms with her personal life comes to a head on “Back to Black” and “Love is a Losing Game,” where Winehouse finally allows herself to take a long, hard look at her sometimes violent relationship, followed by the brutal acceptance that it simply isn’t working. Few pop-leaning albums are ever this direct, the artists typically leaning towards largely making—at most—veiled metaphors towards their tabloid-dominating love life. What makes Back to Black such a legendary release is Winehouse’s refusal to shroud any of her crumbling personal life in her lyrics even as she was skyrocketing to global stardom, a glowing testament that even in pop music, a genre that routinely sees dozens of songwriters work on a single track, honesty still makes for the best material. —Steven Edelstone

7. Richard & Linda Thompson, Shoot Out The Lights

7. Richard & Linda Thompson, Shoot Out The Lights

When husband and wife duo Richard and Linda Thompson began work on their final album together, so much in their lives was in flux. They were without a label and their last LP flopped commercially. Worse still, their relationship was in the midst of falling apart, even with Linda being pregnant with their third child. That uncertainty and frustration bled right into the material they put together for Shoot Out The Lights, with absolute heartbreakers like “Walking On A Wire” (“The grindstone’s wearing me / Your claws are tearing me / Don’t use me endlessly”) and the brutal “Did She Jump Or Was She Pushed?” sitting alongside songs of fury and the most impassioned and agonized guitar playing of Richard’s career. Don’t let his smile on the front cover fool you; this is a man surveying the damage of a broken marriage and amusing himself with the irony of he and Linda arriving at their best work at their lowest point. —Robert Ham

6. Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, The Boatman’s Call

6. Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, The Boatman’s Call

Throughout his storied early career, Nick Cave was terrifyingly confident, a madman behind the microphone screaming tales about murder and sex as his backing post-punk band furiously laid waste to every stage they ever performed on. That all changed with 1997’s The Boatman’s Call, a stark and delicate album of endearing and personal piano ballads—about as major of a departure from the group’s previous nine albums as humanly possible. Centered around Cave’s past breakups with Viviane Carneiro, with whom he was married for six years and had a child with, and his subsequent relationship with PJ Harvey, you can actively feel Cave’s pain throughout, especially on tracks like “People Ain’t No Good,” where you can hear a trembling in his voice, a thousand miles away from his pompous and self assured vocals on “Stagger Lee” or “Red Right Hand.” With no thunderous drums or horror movie-esque strings to hide behind, Cave and his piano let it all out one gentle and heartbreaking track at a time. —Steven Edelstone

5. The Cure, Disintegration

5. The Cure, Disintegration

When you’re despondent after a break-up, listening to Disintegration is like crawling into a warm cocoon of gloom: It’s OKAY. You’re safe here. Robert Smith is going to take good care of you. The first two songs alone deserve the Goth Medal of Honor. “Plainsong,” with that oceanic rush of synthesizer and Smith’s depressive murmurs, sets a remarkable tone. And “Pictures of You” ought to invoice any emo kid who ever used “There was nothing in the world that I ever wanted more / Than to feel you deep in my heart” as an AIM away message. “Lovesong,” which is a real one, written for Smith’s soon-to-be bride Mary Poole, is the brief respite from despair—and good enough that even 311 couldn’t ruin it for good. It feels good to wallow in this record’s gothic sprawl. But yes, listening to it daily is a cry for help. —Zach Schonfeld

4. Liz Phair, Exile in Guyville

4. Liz Phair, Exile in Guyville

Exile in Guyville isn’t your typical woeful breakup album. It’s about leaving men in the dust and flipping the bird on your way out. The 1993 double album roasted the patriarchal dude rock scenes, loosely known as “Guyville,” a toxic environment that’s not hard to identify in today’s music circles. Exile in Guyville wasn’t just about the subversion of gender roles—Phair flat-out beat men at their own male-dominated indie-rock game (she became the first female artist in nearly 20 years to top the Village Voice critics’ poll). “6’1’’” set the tone early with its catchy-as-hell guitar riff and a take-no-prisoners chorus lyric scientifically proven to register on the Richter scale when any woman sings it (“And I loved my life / And I hated you”). Phair took cues from riot grrrl, but she had a less outwardly overbearing front—almost to knowingly lure men in with her pretty smile and then steal the male “use them and lose them” playbook for herself. She wrote openly about female sexuality—addressing one-night-stands on “Fuck and Run” and her unbridled, almost threatening sexual presence on “Canary.” Exile in Guyville was basically the musical equivalent of an Acme anvil being dropped on that cartoon coyote, but instead of Wile E. Coyote, it’s the self-absorbed egos and pea-sized hearts of shitty indie-rock men and ex-boyfriends. —Lizzie Manno

3. Bob Dylan, Blood On The Tracks

3. Bob Dylan, Blood On The Tracks

With good reason, Bob Dylan is most revered for his nearly unparalleled streak of legendary albums in the 1960s (including 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited, and 1966’s Blonde on Blonde), but he saved arguably his finest album ever until 1975, making one of rock ’n’ roll’s most jaw-dropping comebacks with the striking, emotional Blood on the Tracks. Despite being recorded in a ridiculous 10 days (barring a last-minute re-tracking of a few songs), the album remains Dylan’s warmest, richest recording—loads of purring organs, shuffling acoustics, and soulful rhythm sections. But as always with Dylan albums, it’s the words that steal the show, particularly on the bitter epic “Idiot Wind” and the haunting, uplifting “Tangled Up in Blue.” Rock’s most critically acclaimed troubadour kept on releasing wonderful albums after Blood on the Tracks—but he never topped it. —Ryan Reed

2. Joni Mitchell, Blue

2. Joni Mitchell, Blue

Arguably the most vulnerable song on Blue, “A Case of You” is an intimate window into Mitchell’s personal life. In a 1979 Rolling Stone interview, Mitchell said, “The Blue album, there’s hardly a dishonest note in the vocals. At that period in my life, I had no personal defenses. I felt like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes.” Said to be inspired by her breakup with Graham Nash, “A Case of You” is yearning and raw. And interestingly, that’s James Taylor on guitar in the back, Mitchell’s love interest at the time. The saddest Christmas song ever written, “River” captures a flipside to the season. “River” is off the transcendent Blue, which broke ground as one of the most emotionally raw albums ever recorded at that point. The candor of songs on the album like “River” was scary to many record executives, who warned Mitchell that she was sharing too much. But luckily, she didn’t listen. To this day Blue is one of the most beautiful examples of the strength in vulnerability, and by extension, femininity. —Alexa Peters

1. Fleetwood Mac, Rumours

1. Fleetwood Mac, Rumours

Have you ever really been caught up in a band-wide soap opera if you and your fellow bandmates haven’t aired all your dirty laundry on your most famous record? Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours is the ultimate breakup record, written in the crosshairs of Christine and John McVie’s divorce, Mick Fleetwood’s crumbling marriage and Stevie Nicks’ and Lindsey Buckingham’s off-again/on-again/really-really-off-again relationship. Each band member voices their take on their failing relationship—the album is the 11-track musical equivalent of one withering game of he said/she said—and only unite for the epic display of collective, cathartic anger on “The Chain.” At times blistering (“Go Your Own Way”) and at others poignant (“Songbird”), Rumours lives up to its reputation as an enduring examination of love, lust and loss. —Katie Cameron