Harry Styles and Selena Gomez: Growing Up in Public

The Curmudgeon

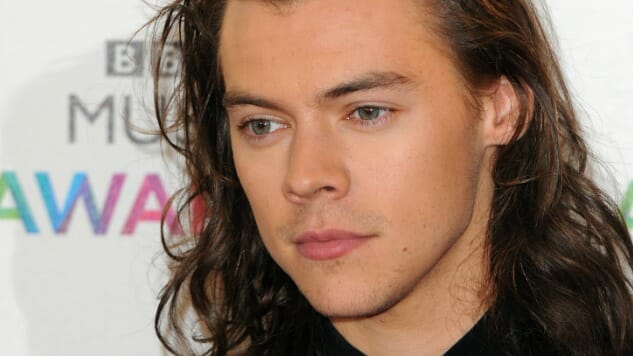

Harry Styles photo courtesy of Columbia Records

Negotiating the transition from adolescence to adulthood is challenging and awkward for all of us, so imagine how hard it is if you’re being watched by millions as you do it. If you have the good luck and dangerous curse to become a celebrity as a teenager, the path to maturity is so treacherous that few can walk it without stumbling.

It’s not just the microscopic scrutiny that comes with fame that’s so hard to handle; the money and license provided by fame is just as perilous. Just think of how much alcohol, drugs, fast cars and bad sex you had as an adolescent. Now imagine how much more you would have had if limited funds and parental restraint hadn’t curtailed your consumption.

When you think about it, it’s not surprising that so many teen pop stars turn into casualties, monsters or both; it’s surprising that some of them don’t. Judy Garland, Frankie Lymon, Tanya Tucker, Michael Jackson, Bobby Brown, Britney Spears and Justin Bieber—the list of teen-celebrity victims goes on and on. At least Garland, Tucker and Jackson made some brilliant adult music in the midst of their private agonies. By contrast, Brown ruined not only his own career but also that of his generation’s greatest vocalist.

That’s what makes the recent albums by the Harry Styles and Selena Gomez so fascinating. Both twentysomething singers have made records that reflect actual young adulthood and not some perpetual teenager’s fantasy of what coming of age would constitute.

You don’t become a grown-up, after all, by grabbing your crotch, talking dirty and wailing about how unfairly someone has treated you. That’s merely adolescence taken out of private spaces and paraded in public. You become an adult by accepting that life is an unpredictable tangle of desires fulfilled and desires denied, of good behavior and bad, of victories followed by defeats and of defeats followed by victories. Styles and Gomez get that.

Styles has turned 26 since he released his second solo album, Fine Line, in December. His newest songs are still obsessed with romantic relationships, but he no longer makes the teenage mistake of separating lust from consequences, happy satisfaction from angry disappointment, urgent desire from lingering feelings. It’s all connected in a mix that’s truer to reality than adolescent assumptions ever knew.

The lyrics hint at this perspective. “All the lights couldn’t put out the dark running through my heart,” he sings on the synth-pounding “Lights Up,” an assessment of one collapsing relationship. “I’m just an arrogant son of a bitch who can’t admit when he’s sorry,” he sings as a way of admitting exactly that on “To Be So Lonely.” “I don’t wanna make you feel bad; I’ve been trying hard not to act the fool,” he warns a potential new lover on “Sunflower.”

But the lyrics are mere signposts to the mix of moods in the music itself. The programmed beats of adolescent lust are still there, but they are overlaid by lush layers of harmony, built from both optimistic major chords and pessimistic minor chords. The melodies rise and fall with the temperature of each affair—sunny one moment, chilly the next. It’s the music more than the words that alerts us to the links between hopeful longing and wounded rejection, represented by pushy rhythms and reluctant keyboard interludes.

It’s as if the up-and-down nature of actual relationships—so different from the conquest-and-move-on nature of high school hook-ups—require more variety in tempos, more contrast within harmonies and more movement in vocal lines. The only reason Styles can pull this off is because his voice is flexible enough to shift from mood to mood and strong enough voice to flesh out each lyric suggestion.

The one-time teen idol of the boy band One Direction had devoted his 2017 solo debut to “dad-rock,” the sound of such ’70s pop-rock baby-boomers as David Bowie, Jackson Browne and Rod Stewart. On this new album, he refers to that earlier discovery of songs he’d “never heard, an old lover’s hippie music.” It was as if he was cutting loose from the sound of his own generation to try on the sensitive singer/songwriter and rowdy bad boy personas of a past era. And he pulled off both.

Having mastered those skills as few in his generation have, Styles has now integrated them into a framework that blends a modern-pop bottom—lean and clean in its precision—with a messier top of conflicting emotions and tension-and-release chord changes. It’s an impressive synthesis, and it suggests that he has moved beyond his teen-pop origins as few of his contemporaries have.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-