An Ode to Jazz Piano

A Curmudgeon Column

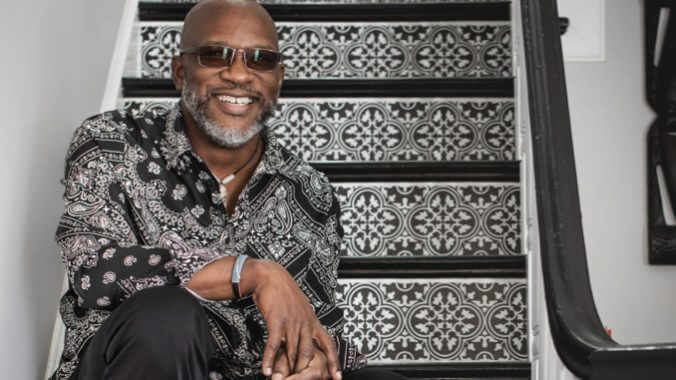

Orrin Evans photo courtesy of DL Media

The Keystone Korner was a legendary jazz club in San Francisco between 1972 and 1983, a place where Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Art Blakey and Dexter Gordon recorded important live albums. Owner Todd Barkan reopened the club in Baltimore in 2019, and it has become a second home for me, a place where I can hear the finest jazz pianists in the world—often the best pianists in any genre.

On Father’s Day last month, for example, I heard pianist Orrin Evans demonstrate how thrilling jazz can be when it refuses to abandon tunes but also refuses to be constrained by them. At times, the pleasures of melody, harmony and groove were unmistakable in Evans’ muscular blues-gospel phrasing, in Gary Thomas’s continuous, unpunctuated tenor-sax lines, and in Sean Jones’ highly punctuated trumpet phrases. At other times, the mere shadow of the song could be detected in the long, cathartic solos by these men or by the rhythm section of bassist Robert Hurts and drummer Marvin “Smitty” Smith—but the song was there nonetheless.

In either case, it was the forward momentum and emotional commitment that kept the audience with the band wherever it ventured. Most of the repertoire were Evans’ compositions from his new album, The Red Door, a recording that features four-fifths of the ensemble at the Keystone (Jones replaced Nicholas Payton). This continuity from studio to stage is invaluable and all too rare in the modern musical economy, where top musicians are often too busy and too expensive to bring on the road. To have a band like this, where every member is a bandleader in his own right, makes every sacrifice worthwhile.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-