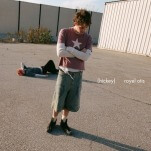

Juliana Hatfield Indulges Her Sweet Tooth on New Olivia Newton-John Covers Album

A career spent blending sunny pop and punk aggression finds its ideal source material in Hatfield's childhood music heroine.

Photo: David Doobinin

In song, as in romance, one never forgets a first love. No matter how cheesy or childish it may seem later, the memory of that initial encounter with music’s emotional power never goes away. For me, it was Paul McCartney and Herman’s Hermits; for you, maybe it was *NSYNC or Hanson. For Juliana Hatfield, it was Olivia Newton-John.

But Hatfield never committed the betrayal that most of us are guilty of. She never spurned her middle-school crush when she got to high school. I may have mocked Herman’s Hermits; you may have mocked Hanson, but Hatfield stayed true to Newton-John. She embraced punk rock as an older adolescent, but did not turn her back on the Australian singer of “Have You Ever Been Mellow.” And it’s that combination of illusion-grinding guitars and heart-on-the-sleeve pop tunes that has made Hatfield one of the most rewarding and underrated artists of the ‘90s indie-rock generation.

“For my whole career, without consciously realizing it, I’ve been trying to integrate Olivia and X, the sweet pop and the messy punk. I’ve always had those two sides to me, not only in what I play but also in what I listen to. I veer back and forth like a pendulum.”

“Even when I fell in love with X,” Hatfield explains, “I never lost my love for Olivia. I never hid it. Different parts of my personality are drawn to different musics. The angry part of me is attracted to more aggressive music and more aggressive performances, like Exene’s voice, or more humor maybe, like The Replacements and Devo. The idealistic part of me is drawn to melodies and harmonies, like Olivia’s singing. For me it’s fine to like Olivia Newton-John and Black Flag.”

Far from hiding her first musical love, Hatfield is celebrating it on the new album Juliana Hatfield Sings Olivia Newton-John, which comes out Friday on American Laundromat Records. With her longtime rock ‘n’ roll rhythm section of drummer Pete Caldes and bassist Ed Valauskas, Hatfield remakes 13 of Newton-John’s songs (one of them in two different mixes), including seven singles that reached the U.S. pop top 10. Hatfield scuffs them up a little but not so much that they lose their essential, unironic sweetness.

“For my whole career, without consciously realizing it,” Hatfield says, “I’ve been trying to integrate Olivia and X, the sweet pop and the messy punk. I’ve always had those two sides to me, not only in what I play but also in what I listen to. I veer back and forth like a pendulum. On this new record, I felt the need to rough up Olivia’s songs, to muss up their hair, to add a little grime. Because that’s who I am; I’m not as pristine or as strong a singer as her. So I had to play to my own strengths—to my scrappiness.”

Hatfield was 10 years old, living in the Boston suburb of Duxbury, when the movie Grease and its soundtrack were released in 1978. She was fascinated by the character of Sandy, played by Newton-John, an exchange student from Australia and a goody-good girl who falls for the greaser bad boy Danny, played by John Travolta. Like the fifth-grader Hatfield, Sandy was essentially a rule-abiding girl who was attracted to the rule-breaking world of juvenile delinquents and rock music. Hatfield took her cue from a role model who was able to cross that boundary without compromising her principles.

“When I was a kid,” Hatfield recalls, “I just related to Olivia’s sense of innocence, especially when she was singing. I even had a friend curl my hair so I looked like Sandy. I like to think that Sandy was putting on that bad-girl persona as a goof, because she realized that this was just a game that people play. I don’t like to think she put on a mask just to get the guy. I didn’t want to believe that you have to sex yourself up to find love. I never made that choice to change myself like that. Maybe my life would be easier if I had.”

Hatfield had a different interpretation of the punk ethos than some of her friends. For her, punk wasn’t defined by drugs and promiscuous sex; it was defined by staying true to one’s own moral code, whatever that was. That’s why Newton-John still made sense to her when she picked up a guitar and started playing punk rock, even persuading her high school cover band to add some X songs to a setlist dominated by Journey and Styx. When she was confronted by peer pressure to take drugs she didn’t want and to sleep with boys she didn’t like, the punk move was to resist, not give in. In this regard, Olivia Newton-John and Exene Cervenka were on the same page.

“Maybe it was in my DNA,” she suggests. “Maybe I had a punk heart; I didn’t want to do things because everyone else was doing them. I was impervious to peer pressure, and that isolated me a bit, because I wouldn’t give in and do what the other kids did. So I felt an affinity with Olivia, because she also had this good-girl curse. I felt like an outcast because all my friends in high school and college were doing drugs, getting drunk and having sex, but I didn’t want to. I was hanging out with these people, but it didn’t feel right to me; I wasn’t ready or interested. I knew I would do things on my own time line.”

It was in 1986 at Boston’s Berklee College of Music that she formed The Blake Babies with guitarist John Strohm and drummer Freda Boner. The Lemonheads’ Evan Dando was briefly the group’s bassist, and when he left, Hatfield was persuaded to shift from guitar and emulate Dando’s unusually melodic bass lines. Even after she returned to guitar in 1994 with her own group, she ever after wrote tuneful, prominent parts for her bassists to contrast against her brittle guitar riffs. “I like melodic bass players like Evan and Paul McCartney,” she says. “I get bored holding down the bottom, and I love melody, so I played that way. The bass players I hire know what I like to hear. It frees up the guitar to not be so melodic. I always have some anxiety about my records becoming too monochrome or not grooving enough, and I always go to melody to fix things.”

The Blake Babies were a delightful indie-rock outfit, but the trio eventually broke up as Hatfield wanted to further emphasize the pop elements in the group’s sound, a move her bandmates resisted. The divergent opinions took shape as arguments over Wilson Phillips, the trio formed by the daughters of Brian Wilson and John and Michelle Phillips. Hatfield loved the vocal-harmony echoes of Newton-John she heard in hits like “Hold On,” but Strohm and Boner dismissed it as juvenile fluff. “When I left The Blake Babies,” she says, “I was miserable because I wanted to do my own thing, but I missed being in a gang—a band is like a gang that has your back. The other members are a cushion against criticism. But I wanted to have more control over the music; I wanted to be able to say, ‘This is how I want to do it, and that’s how we’re going to do it.”

Earlier this spring, American Laundromat Records released a remastered 25th anniversary vinyl edition of Hatfield’s debut solo album, 1992’s Hey Babe, in a gatefold package. With help from such friends as Dando, John Wesley Harding and Mike Watt, she crafted a new balance between the pop and rock elements in her music. The lead-off track, “Everybody Loves Me but You,” boasts a classic guitar riff, pitted against Hatfield’s rolling bass line, as she wails that the one person whose love she craves is the one person who won’t offer it.

“For many years, I’d had an aversion to that album,” she confesses. “I didn’t like to think about it. But now I appreciate it. I like some of the prog-ish things at the end, those extended musical passages clearly influenced by Dinosaur Jr., which I was so into at the time. ‘Forever Baby’ and ‘I See You” were my pop instincts coming out when I wanted to be rock ‘n’ roll. All the cool kids were making rock music, but I couldn’t help myself from making pop songs like ‘Forever Baby.’”

The album got her a deal with Atlantic Records and led to her breakthrough album, 1993’s Become What You Are. “My Sister” hit No. 1 on Billboard’s Modern Rock chart; “Spin the Bottle” appeared on the soundtrack for the zeitgeist movie Reality Bites, and Hatfield wound up on the cover of Spin. “My Sister” is a magnificent achievement, using the phrases “I love my sister” and “I hate my sister” to capture the contradictory feelings we often have about the people closest to us. The fact that Hatfield didn’t actually have a sister hardly mattered, given the infectious hook and the evocative details about firecrackers and a Violent Femmes concert.

“I wasn’t trying to put one over on people; it was all about how I was feeling,” she explains. “I just wanted to express the pain I was in. The sister was a metaphor, a construct I used to express my feelings of longing and inadequacy.”

Read: Paste’s review of Juliana Hatfield’s 2017 album, ‘Pussycat’

She made two more albums for Atlantic, one (Only Everything) that was released and one (God’s Foot) that never was. She kept working nonetheless and has released more than 20 titles for the Bar/None, Zoe, Island, Koch and Barsuk labels, her own record company, Ye Olde Records, and more recently American Laundromat. She has mostly worked under her own name, but she has also recorded as the Juliana Hatfield Three, Some Girls, Minor Alps, The I Don’t Cares and the reunited Blake Babies.

Throughout it all, her music derived its power from the push-and-pull between its punk storm clouds and its pop sunniness. One could hear that in the tension between the hooky melodies of the songs and the harsh noise of the band, between the lyrics’ despairing doubt and shrug-it-off jokes and between her girlish soprano and her dirty guitar.

“I was kind of tortured by my voice for a long time,” she told me in 2008. “I wanted to have a low, cool, serious voice like Chrissie Hynde or Patti Smith. I started smoking at one point hoping it would give me a raspier tone. I only smoked for five years, because I realized that it would take a lifetime for me to sound like Marianne Faithfull. I wanted to sound tough and cool and rock ‘n’ roll. I thought people wouldn’t take me seriously because of my voice. But I’ve learned to love my voice for its uniqueness and originality. I don’t think I sound like anyone else.”

In her mind, the personification of her music’s romantic side was Newton-John, who sang as if she’d never smoked. If Hatfield could understand how the songs of her childhood hero worked, maybe she could understand her own music better.

“A year and a half ago,” she recalls, “I was going to go see Olivia in concert for the first time, but she ended up canceling that string of shows because her cancer had come back. That’s when I decided to make the album. It was just an idea that popped into my mind, because I was immersed with her music again in preparation for the concert. Once we were in the studio, we found ourselves translating those well-written songs through this traditional unit of guitar, bass, drums and my weird voice. We did them as if they were songs we had written.”

My favorite memory of Hatfield comes from her appearance as part of the women’s music festival, Lilith Fair, when it came to Maryland’s Merriweather Post Pavilion in 1997. She was relegated to a tiny side stage high on a grassy hillside, but her quartet delivered the day’s best set. Hatfield, her brown bangs falling into her eyes, her tall, slender frame inside a sleeveless, purple-satin blouse, and a sunburst Les Paul guitar strapped around her neck, climaxed the set with “My Sister.”

The jangly, clanging chords filled the lawn as Hatfield see-sawed between her grateful and resentful attitudes toward her fictional sibling. But the band pulled back for the final verse, and throughout the crowd of young women—some as young as Hatfield had been when she first saw Grease, their eyes similarly widening with a first musical love—began softly singing along without being asked, “I miss my sister, I miss my sister.”

Perhaps Hatfield’s imaginary sister is Newton-John, a calmer, more assured older sibling, experienced enough to show you how to say “yes” to some things and “no” to others, optimistic enough to get you through lowest lows, a template to emulate and rebel against, someone to measure yourself against for the rest of your life.

“My love for Olivia’s music is not nostalgia,” Hatfield says, “because I still love it and get pleasure from it. There’s something about the timbre of her voice that homes in on my pleasure center. She was never desperately pleading for acceptance or attention from people like other pop stars were. She had this great solid core that is still very appealing to me; she felt very centered. So many stars come across as emotional messes, but she seemed like she really had her shit together.”