No Album Left Behind: Our Native Daughters’ Songs of Our Native Daughters

A folk supergroup addresses the racial oppression in roots music's origins

Music Reviews Our Native Daughters

Over the course of 2019, Paste has reviewed about 300 albums. Yet, hundreds—if not thousands—of albums have slipped through the cracks. This December, we’re delighted to launch a new series called No Album Left Behind, in which our core team of critics reviews some of their favorite records we may have missed the first time around, looking back at some of the best overlooked releases of 2019.

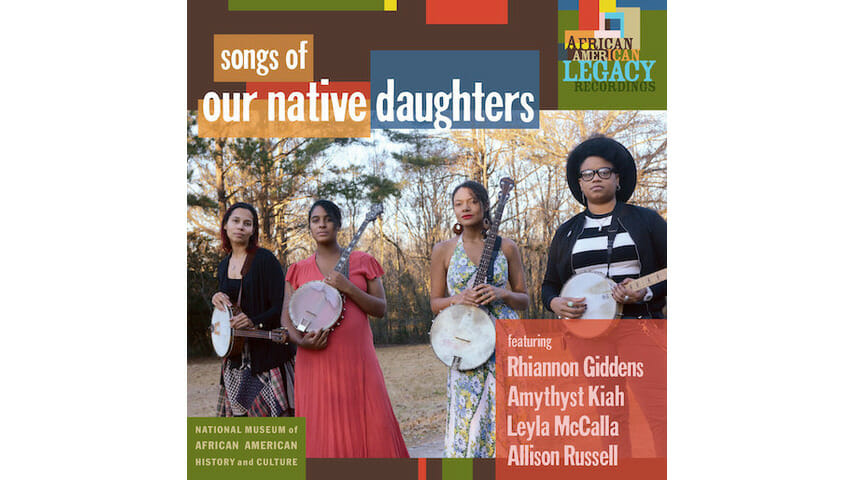

“This album confronts the ways we are culturally conditioned to avoid talking about America’s history of slavery, racism and misogyny,” writes Rhiannon Giddens in the extensive liner notes that accompany Songs of Our Native Daughters, the debut from a supergroup comprised of Giddens, Tennessee solo artist Amythyst Kiah, Haitian-American multi-instrumentalist Leyla McCalla and Allison Russell of Po’Girl and Birds of Chicago. This statement of purpose unites the album’s 13 historically-attuned songs, which draw from 17th, 18th and 19th century musical and literary sources in addition to the musicians’ own histories of discrimination, trauma, resilience and community.

But Giddens’ mission statement can also be read as a reflection on the blurry-edged genre that’s come to be known as “folk,” “roots” or “Americana” music in recent years. These signifiers should, in theory, be capacious and inclusive; technically speaking, they refer to little more than the presence of acoustic stringed instruments in a piece of music and some aesthetic or thematic connection to America’s past. In reality, however, the contemporary genre of folk music in America draws frequent and legitimate critique for having become primarily (though not exclusively) the domain of white artists—and for continually tapping a market sector that is upper-class and also white.

The silence and erasure that Giddens names when introducing Our Native Daughters also partly explains this market phenomenon—white artists making so-called “roots” music that appeals to other white consumers. For white listeners, folk music can feel like a salve, a comfort or a space for peaceful communion with other musicians or music-lovers. But it’s only possible to find straightforward enjoyment in this music if we neglect the role that racial oppression has played in obscuring the music’s historical roots and replacing them with uncomplicated material sanded down by amnesia.

At the center of Our Native Daughters’ project lies the banjo—an instrument, Giddens explains, whose origins lie in West Africa but whose place in American culture has been jostled and thieved by the slave trade, the popularity of blackface minstrelsy in the 19th century and (although Giddens does not mention this) the Mumford-ification of the instrument into a tool that’s often associated with bearded dudes making foot-stomping, easy-listening music on festival stages.

All four members of Our Native Daughters are experts at playing the banjo, whether the 5-string, tenor or minstrel variety. Giddens is already well established as a virtuosic multi-instrumentalist, having gained notoriety as the frontwoman of Carolina Chocolate Drops, as a MacArthur “Genius” Fellow and recently through solo albums Tomorrow Is My Turn (2015) and Freedom Highway (2017). Each member of Our Native Daughters brings distinctive ideas and sounds to the project while generously ceding space to one another when appropriate. The album stands on its own not just because of Giddens’ vision and star power, but equally because of Kiah’s forthright songwriting and attention-grabbing contralto, McCalla’s explorations of Afro-Caribbean rhythms and Russell’s remarkably personal narratives about the trauma that she and her ancestors have survived.

Songs of Our Native Daughters is not only a musical project but also a scholarly one, delving into historical archives and unearthing source material that includes slave narratives, family genealogy, abolitionist poetry and the Briggs’ Banjo Instructor of 1855, the earliest known minstrel banjo tutorial. In every case, the creators lift a scrap of history—a couplet, a melody, a first-person account—and follow it like a clue, finding voices for silenced figures and contemporary analogues for centuries-old concerns.

The most obvious example of the latter would be “Barbados,” a pastiche of historical references that includes a bitterly satirical 1788 poem called “Pity for Poor Africans” by William Cowper and a line of music believed to be the first western notation of New World enslaved music, transcribed by D. W. Dickson in Barbados in the 18th century. The guitar-and-banjo melody is bookended by Giddens reciting two monologues: first, Cowper’s poem about white complicity in the slave trade (“I pity them greatly but I must be mum / For how could we do without sugar and rum?”), and second, producer Dirk Powell’s application of the poem’s sentiments to contemporary global trade practices, substituting for slaves the underpaid mine and factory workers whose labor produces “the garments we wear, the devices we own.” The parallelism might seem heavy-handed without the interpolated musical passage, which, the liner notes acknowledge, was transcribed inaccurately because of Dickson’s limited understanding of non-western rhythms and melodies. Both music and lyrics—quoted and riffed upon—acknowledge uncompensated labor that persists thanks to the tastes and miopic vision of distant consumers.

Each track on Songs of Our Native Daughters could yield paragraphs of description and interpretation, and for its combination of cerebral historiography and sheer beauty as music, each song deserves a close listen. After spending almost a year with the album, I’ll highlight two tracks I haven’t been able to shake: Penned and sung by Allison Russell, “Quasheba, Quasheba” is a second-person address to an ancestor who was sold to a slave trader on the coast of Ghana and lived the remainder of her life on a sugar plantation in Grenada. Over a steady backbeat and the friction created by a rare electric guitar glancing off her bandmates’ acoustic instruments, Russell narrates the atrocities and traumas that wracked Quasheba’s life, but also the persistence that allowed her to survive and Russell, her descendent, to exist: “Blood of your blood, bone of your bone / By the grace of your strength we have life.”

On “Mama’s Cryin’ Long,” Our Native Daughters lay their stringed instruments down momentarily to foreground call-and-response vocals, led by Giddens, unfolding over handclaps and a single drum played by percussionist Jamie Dick. The song reanimates an enslaved woman who, according to written sources, killed the overseer who repeatedly abused her. Told from her child’s perspective in looping spurts of information like “Mama’s dress is red / It was white before,” the story becomes increasingly devastating to follow. Our Native Daughters’ performance bears witness to the woman’s life and death by giving breath to words that were transcribed, by heroic gestures of testimony and preservation, in an antebellum context.

Through tracks like these, Our Native Daughters teach their audience how to listen—not just to the complex layers of source material and invention that constitute the songs on their album. Their work, additionally, insists that those of us who listen to, make and love “folk” music must become ever-more aware of the countless acts of violence that brought it into being, and find meaningful ways to reckon with that history.

Revisit Rhiannon Giddens’ Paste session from earlier this year: