No Album Left Behind: Our Native Daughters’ Songs of Our Native Daughters

A folk supergroup addresses the racial oppression in roots music's origins

Over the course of 2019, Paste has reviewed about 300 albums. Yet, hundreds—if not thousands—of albums have slipped through the cracks. This December, we’re delighted to launch a new series called No Album Left Behind, in which our core team of critics reviews some of their favorite records we may have missed the first time around, looking back at some of the best overlooked releases of 2019.

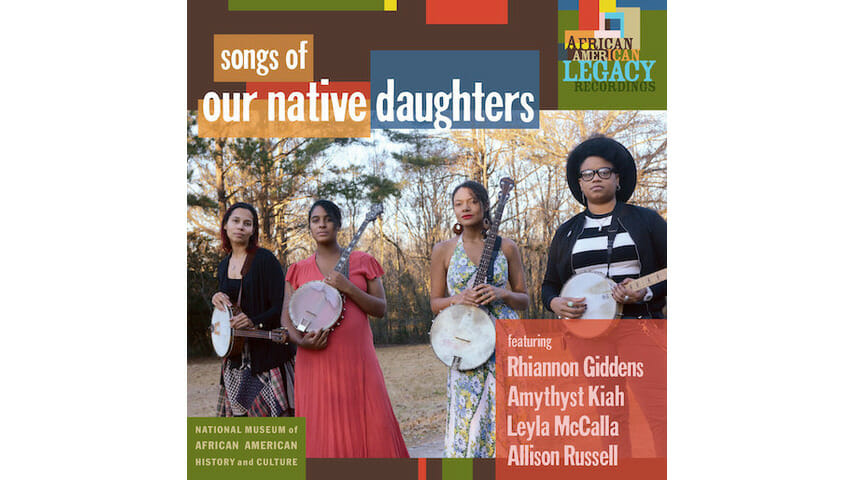

“This album confronts the ways we are culturally conditioned to avoid talking about America’s history of slavery, racism and misogyny,” writes Rhiannon Giddens in the extensive liner notes that accompany Songs of Our Native Daughters, the debut from a supergroup comprised of Giddens, Tennessee solo artist Amythyst Kiah, Haitian-American multi-instrumentalist Leyla McCalla and Allison Russell of Po’Girl and Birds of Chicago. This statement of purpose unites the album’s 13 historically-attuned songs, which draw from 17th, 18th and 19th century musical and literary sources in addition to the musicians’ own histories of discrimination, trauma, resilience and community.

But Giddens’ mission statement can also be read as a reflection on the blurry-edged genre that’s come to be known as “folk,” “roots” or “Americana” music in recent years. These signifiers should, in theory, be capacious and inclusive; technically speaking, they refer to little more than the presence of acoustic stringed instruments in a piece of music and some aesthetic or thematic connection to America’s past. In reality, however, the contemporary genre of folk music in America draws frequent and legitimate critique for having become primarily (though not exclusively) the domain of white artists—and for continually tapping a market sector that is upper-class and also white.

The silence and erasure that Giddens names when introducing Our Native Daughters also partly explains this market phenomenon—white artists making so-called “roots” music that appeals to other white consumers. For white listeners, folk music can feel like a salve, a comfort or a space for peaceful communion with other musicians or music-lovers. But it’s only possible to find straightforward enjoyment in this music if we neglect the role that racial oppression has played in obscuring the music’s historical roots and replacing them with uncomplicated material sanded down by amnesia.

At the center of Our Native Daughters’ project lies the banjo—an instrument, Giddens explains, whose origins lie in West Africa but whose place in American culture has been jostled and thieved by the slave trade, the popularity of blackface minstrelsy in the 19th century and (although Giddens does not mention this) the Mumford-ification of the instrument into a tool that’s often associated with bearded dudes making foot-stomping, easy-listening music on festival stages.

All four members of Our Native Daughters are experts at playing the banjo, whether the 5-string, tenor or minstrel variety. Giddens is already well established as a virtuosic multi-instrumentalist, having gained notoriety as the frontwoman of Carolina Chocolate Drops, as a MacArthur “Genius” Fellow and recently through solo albums Tomorrow Is My Turn (2015) and Freedom Highway (2017). Each member of Our Native Daughters brings distinctive ideas and sounds to the project while generously ceding space to one another when appropriate. The album stands on its own not just because of Giddens’ vision and star power, but equally because of Kiah’s forthright songwriting and attention-grabbing contralto, McCalla’s explorations of Afro-Caribbean rhythms and Russell’s remarkably personal narratives about the trauma that she and her ancestors have survived.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-