The 10 Best Movies on Pluto TV

Pluto TV is best-known for its livestreaming of TV shows and movies, but to find what you’re looking for with the reliability of a streamer, check out its free and on-demand movies. Its UI might be a little tricky to navigate, especially since it’s got that autoplaying “remember, it’s TV!” thing happening, but once you switch to the On Demand offerings, you’ll see that there are a ton of movies available, including Oscar-winners, Bruce Lee movies, and oodles of horror. Its user interface might be a bit clunky (or exactly what you want if you just miss having regular ol’ TV to flip through), but the selection is almost always on point.

Here are the 10 best movies on Pluto TV:

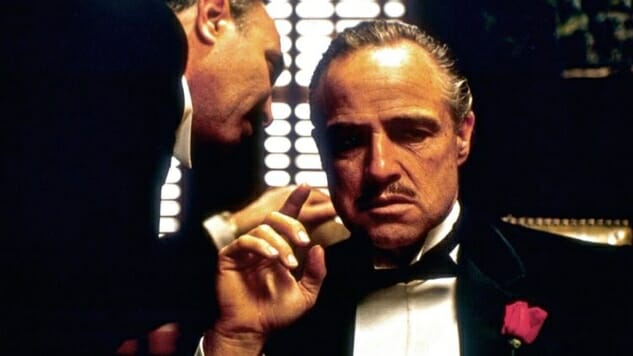

1. The Godfather

Year: 1972

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Stars: Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Richard Castellano, Robert Duvall, Sterling Hayden, John Marley, Richard Conte, Diane Keaton

Rating: R

The definitive immigrant story/definitive American tragedy: These are the awful things we are forced to do, and this is whom we do them for. The best mob stories ask: “How do I take care of me and mine?” How far are you willing to go to protect your own? In The Godfather and its sequels, the story of the Corleone family becomes the centerpiece of a deep meditation on family and power. Francis Ford Coppola answers: Ultimately, you will lose one in the vain pursuit of the other. During the second film, Family don Michael’s (Al Pacino) wife Kay (Diane Keaton, unrecognizable in her youth) gets her one really powerful scene as she reveals to her husband that she had an abortion because she can’t bear the thought of raising another child in the mob. He wouldn’t understand, she rants, because of “this Sicilian thing that’s been going on for 2,000 years!” Before, we flash back to 1941 and the fight that results from Michael revealing his enlistment in the Marines to his family: either the beginning of his personal fall or one last reminder that he’s always viewed himself as apart, as better. True tragedy comes from a fatal, internal flaw, and something about this scene is meant to suggest his. His family leaves him in the room alone. The only other times that both Michael and Vito (Marlon Brando; Robert De Niro) are alone on screen in the films occur in the tense moments before they kill—always in explicit defense of the family. Flash forward to Michael on a park bench by himself —years later, after he’s driven away his wife and his sister and seen countless people killed, many by his own order. The lonely horn section of the waltz motif plays us out. Long before that, Michael asks his mother if a man can lose his family in the struggle to protect it. It’s a question we’ve already answered. These are the awful things we are forced to do, and this is whom we do them for. At least, for Coppola, that’s what we tell ourselves. —Ken Lowe

2. Coming to America

Year: 1988

Director: John Landis

Stars: Eddie Murphy, Arsenio Hall, James Earl Jones, John Amos, Madge Sinclair, Shari Headley

Rating: R

If this Eddie Murphy and Arsenio Hall classic, care of their team-up with John Landis (Blues Brothers), consisted only of the barbershop scenes inside of My-T-Sharp and nothing else, it would still be one of the greatest comedies of all time. As Prince Akeem from the fictional African country of Zamunda, Murphy travels to the great United States of America to evade his arranged marriage and find true love (in Queens, obviously). Akeem encounters all of the wonders of black America, saturated with satirical twists—the black preacher (via Hall as the incomparable Reverend Brown), the club scene, the barbershop, hip-hop culture and Soul Glo, it’s all here—but cameos from actors like Cuba Gooding Jr., Samuel L. Jackson, Louie Anderson and Murphy’s Trading Places co-stars Don Ameche and Ralph Bellamy take the Coming to America experience to a whole new level. An excellent comedy and a great tribute to New York City, this story of a prince just looking to be loved is a must-see for everyone—including those of us who’ve already seen it. —Shannon M. Houston

3. 28 Days Later

Year: 2002

Director: Danny Boyle

Stars: Cillian Murphy, Naomie Harris, Christopher Eccleston, Megan Burns, Brendan Gleeson

Rating: R

The classical zombie film was effectively dead by the time 28 Days Later came along in 2002 and completely reanimated the concept. (And yes, we all know that the “infected” in this film aren’t technically zombies, so please don’t feel that you have to remind us.) The definition of “zombies” is fluid, and always expanding. Here, they’re living rather than dead, poor souls infected by the “rage virus” that makes them run amok, tearing through whatever living thing they see. It’s a modernization of the same fears that powered Romero’s ghouls—unthinking assailants who will stop at nothing and are now more dangerous than ever because they move at a full-on sprint. It’s hard to overstate how big a quantum leap that mobility was for the zombie genre–the early scenes of 28 Days Later where Jim (Cillian Murphy) tries to navigate a deserted London in hospital scrubs, chased by fast-moving zombies, did for this genre what Scream did for the slasher revival, sans the humor. Indeed, 28 days Later is a dead-serious horror film, marking a return to seeing these types of creatures as a legitimate, frightening threat. It’s indicative of another trend of the 2000s, which was to reimagine the classic rules of zombie cinema to fit the needs of the film. The Zack Snyder Dawn of the Dead remake replicated a lot of this film’s DNA when it was released two years later, although it marries the concept with the more traditional Romero ghoul. Together, those two movies gave birth to the concept of the 21st-century serious zombie film. —Jim Vorel

4. Good Will Hunting

Year: 1997

Director: Gus Van Sant

Stars: Robin Williams, Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, Stellan Skarsgård, Minnie Driver

Rating: R

The story of a genius janitor capable of solving the world’s most difficult mathematical problems, Will (Matt Damon) is both exasperating and lovable as the Boston boy reluctant to live up to his true potential. Robin Williams takes the oft-clichéd mentor paradigm and turns it into a wholly original character as Will’s therapist Sean. But what’s special about this film is the way Gus Van Sant captures the existential angst and, ultimately, the frustrated striving of a brilliant boy from the wrong side of the tracks. Matt Damon and Ben Affleck star in their own breakthrough roles as best friends closer than even blood brothers. Though the movie touches on heart-wrenching topics like childhood abuse and heartbreak, the sarcastic humor and witty banter are just as memorable. Effortlessly charming and never overwrought. —Amy Libby

5. Stranger Than Fiction

Year: 2006

Director: Marc Forster

Stars: Will Ferrell, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Dustin Hoffman, Queen Latifah, Emma Thompson

Rating: PG-13

Stranger Than Fiction is the film that should have represented Will Ferrell’s big dramatic break, a sadly underseen and sweetly winning tale of modern fantasy, about a sadsack IRS agent who wakes up one morning to find himself having been thrust overnight into a literary quandary: He suddenly seems to be the main character of a novel, and he can hear the author’s narration in his head, warning him of an impending and tragic death. That knowledge of his upcoming demise serves as an impetus for poor Harold Crick (Ferrell) to start really living his life for the first time ever, embracing the messiness of human experience, romance and sacrifice, even as he attempts to track down the source of the authorial voice (Emma Thompson, neurotic to the max) and kindly ask if she’d reconsider killing him. It’s all somewhat shmaltzy, but you can’t help but be won over by Ferrell’s warmth and plainspoken decency as Harold, and Dustin Hoffman is particularly good as a wry literature professor who takes a grudging interest in Harold’s case, helping him attempt to decode what kind of story he might be in. Stranger Than Fiction steers itself in a surprisingly profound direction as it ponders the intersection of fate and responsibility, both for those who understand the consequences of their action or inaction, and the creators whose work grows beyond their ability to control. —Jim Vorel

6. Wayne’s World

Year: 1992

Director: Penelope Spheeris

Stars: Mike Meyers, Dana Carvey, Rob Lowe, Tia Carrere, Brian Doyle Murray, Lara Flynn Boyle

Rating: PG-13

Ever since the genesis of the duo on SNL, Wayne Campbell and Garth Algar were always proud broadcasters from “Cable 10 Public Access in Aurora, Illinois,” and those Midwestern sensibilities lie at the very heart of both the sketches and the two feature films. Wayne is exactly the sort of genial, goodhearted but fairly dim everyman slacker so often lampooned in other shows of the same period based in the Midwest (most notably MST3k). He still lives in the basement of his parents’ suburban home, the big fish in an extremely small pond of local broadcasting, without any real ambitions even to expand the scope of Wayne’s World. One might actually say his lack of vision or ambition is presented as a virtue: Wayne and Garth are just simple people, happy with what they have, where Rob Lowe’s antagonist character, Benjamin, is an upwardly mobile schemer. These are exactly the roles you expect to see characters play when set in the realistic, somewhat milquetoast setting of Illinois suburbia. —Jim Vorel

7. Point Break

Year: 1991

Director: Kathryn Bigelow

Stars: Patrick Swayze, Keanu Reeves, Gary Busey, Lori Petty

Rating: R

There are plenty of late ’80s/early ’90s action flicks anyone could cite, but few epitomized the near-paradoxical dudebro melodrama of the era with as much heart and sincerity as Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break. Johnny Utah—played by the only one on this Earth who could believably play a human being named that, Keanu Reeves, with the sedate gusto that would further vaunt him to action star fame—is an FBI agent who must learn how to be an X-treme surfer in order to infiltrate a cadre of bank robbers led by Bodhi (Patrick Swayze in peak hunk form). Inevitably, Johnny and Bodhi bond—and then clash—over their mutual thirst for salt water, high-stakes adventure and the love of a strong woman (Lori Petty, a wonderfully anti-typical blockbuster love interest), climaxing in the now-iconic scene of Reeves, consumed by X-treme angst, hollering and firing his gun into the sky, a scene so cemented in the cinematic canon that any aging, pacifist Millennial who has never fired a gun before still secretly wet-dreams about having the chance to do the same before their time on this godforsaken planet runs out. —Dom Sinacola

8. The Wolf of Snow Hollow

Year: 2020

Director: Jim Cummings

Stars: Jim Cummings, Robert Forster, Riki Lindhome, Chloe East, Jimmy Tatro, Kevin Changaris, Skyler Bible, Demetrius Daniels

Rating: R

Snow Hollow police officer John Marshall (Cummings) unsteadily balances Alcoholics Anonymous meetings with the travails of raising his teen daughter, Jenna (Chloe East), looking after his ailing father, Hadley (Forster), maintaining diplomatic relations with his ex, and keeping a lid on his volcanic temper. When a woman (Annie Hamilton) is torn to shreds on a weekend visit to John’s ski resort hometown, just moments before her boyfriend (Jimmy Tatro) planned to propose to her, John stretches to his limits and beyond in his pursuit of the killer, who everyone concludes with baffling swiftness is a werewolf rather than a man. His peers’ and subordinates’ stumblebum character and the ass-backwardness of Snow Hollow itself act like gasoline as is. The consensus that the town is under attack from a mythical creature is the straw that makes the vein in John’s neck go taut with anger. The Wolf of Snow Hollow lands in the space where horror and humor meet, mining laughter in mourning and custody battles. Cummings’ laughs are the sort that signal discomfort: His punchlines are razor sharp, which make the movie’s surrounding unpleasantries go down more easily. Watching a policeman get physical with anybody who sufficiently pushes his buttons induces squirms. When fellow officer Bo (Kevin Changaris) accidentally says too much about the murders in front of reporters, John calls him over to a snowbank and starts smacking the poor schmuck around, a moment that would tip over into pure darkness without the aid of a lighthearted soundtrack and the slapstick of their scuffle. Regardless, the point is made: John’s on edge, and his edge is surprisingly amusing. The wry, snappy banter gives The Wolf of Snow Hollow a prickly skin, and the restrained application of FX gives it tension. At just under 80 minutes, that economy is key. It’s not so much that the horror is elevated as controlled. But rather than clang with the innate savagery of the werewolf niche, Cummings’ command over his material gives the film a certain freshness. He tames the monster in the man so that the man is all that’s left, for better and for worse. John isn’t perfect, but an imperfect man need not be a beast.—Andy Crump

9. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer

Year: 1986

Director: John McNaughton

Stars: Michael Rooker, Tom Towles, Tracy Arnold

Rating: X

Henry stars Merle himself, Michael Rooker, in a film which is essentially meant to approximate the life of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, along with his demented sidekick Otis Toole (Tom Towles). The film was shot and set in Chicago on a budget of only $100,000, and is a depraved journey into the depths of the darkness capable of infecting the human soul. That probably sounds like hyperbole, but Henry really is an ugly film–you feel dirty just watching it, from the filth-crusted urban streets to the supremely unlikeable characters who prey on local prostitutes. It’s not an easy watch, but if gritty true crime is your thing, it’s a must-see. Some of the sequences, such as the “home video” shot by Henry and Otis as they torture an entire family, gave the film a notorious reputation, even among horror fans, as an unrelenting look into the nature of disturbingly mundane evil. —Jim Vorel

10. Django

Year: 1966

Director: Sergio Corbucci

Stars: Franco Nero, Loredana Nusciak, José Bódalo, Ángel Álvarez, Eduardo Fajardo

Rating: NR

Ah, Django. Who can say no to that soundtrack? Who can pass up the grizzled mug of Franco Nero, or the filmic stylings of Sergio Corbucci? Quentin Tarantino certainly couldn’t, and thus we have Django Unchained as a delightfully violent relic of 2012 (see No. 85). More importantly, we have Django and we have Django, a righteous, coffin-dragging, gunslinging, erstwhile Union soldier wandering the United States-Mexico border who winds up caught between tattered remnants of the Confederacy and Mexican revolutionaries. Django cuts a figure of cool reserve, the kind we’ve come to associate with the Spaghetti Western’s antihero archetype; he’s out for a cause, his own cause, and he sees his cause realized through the subterfuge and manipulation favored by his forebears (A Fistful of Dollars, and by extension Yojimbo). But as great as the character is, it’s Django’s level of violence plus Corbucci’s gifts as a craftsman that make the film indelible. If it’s tame by our standards today, then consider that Django was a new ceiling in screen bloodshed back in 1966, and rife with pissed-off political and social subtext to match. Corbucci’s pastiche of spiritual hypocrisy, unveiled rancor for the Ku Klux Klan, and contempt for glorified misogyny make for a dizzying, surreal genre experience against his mud-caked, bloodstained backdrop. Django isn’t just one of the best Spaghetti Westerns of all time. It’s one of the best Westerns of all time, period. —A.C.